Early encounters between nationals from India and Indo-Caribbean people in America were not very warm, friendly, congenial, convivial, and hospitable as say the experience in encounters among fellow Indo-Caribbeans in this strange new homeland. The Indo-Caribbeans, children or descendants of ‘coolies’ or lower class indentured laborers or girmityas, were treated with disdain and hauteur or looked down upon by Indian nationals. The behavior of the two groups towards each other was largely different and unequal with the Indo-Caribbeans very warm and welcoming towards their kin from India or from other parts of Asia or from Africa and elsewhere and the Indian nationals (from India and other parts of South Asia) not exhibiting similar deference towards their far away kin from the Caribbean. They were described as aloof, standoffish, distanced, and detached and didn’t mix with Indo-Caribbeans. They had their own network and didn’t network with Indo-Caribbeans. Indians from Africa, Singapore, Burma, Malaysia, and elsewhere were far more friendly and engaging with Indo-Caribbeans than counterparts from India. The behavior of Indians from Burma, Kenya, Uganda, Ghana, and other African and Asian countries were much different from their counterparts from India. The former treated Indo-Caribbeans with admiration and deference – very warm as compared with how nationals from India treated Indo-Caribbeans. (This writer was told that similar behavioral tendencies were exhibited and or experienced between the Indo-Caribbeans and nationals from Indian in England and Canada as well as in Holland and France and ditto the relationship between Fijian Indians and Indian nationals in America, Canada, and UK). Indo-Caribbeans everywhere complained that their experiences revealed that there was weak affection by Indian nationals for Indo-Caribbeans and limited engagement particularly during the early encounters from the 1960s thru 1990s in the USA. They didn’t see Indo-Caribbeans as Indians. (This writer was told the above description also accurately captures the relationship between Indo-Caribbeans and Indian nationals in UK and Canada).

Indo-Caribbeans and nationals from India came to the USA as migrants around the same time post 1965 although Indian nationals were substantially larger in number and came to America mostly as professionals (from among the wealthier sections in India) and foreign students while Indo-Caribbeans were primarily from the lower stratum of their home countries, victims of racial discrimination. Early Indian migrants were college graduates whereas Indo-Caribbeans were coming to the USA for a tertiary education; the limitations of their home countries and racial discrimination did not allow for a tertiary education. Indo-Caribbeans (mostly from Trinidad, Guyana, Jamaica, Grenada, St. Lucia, and other islands) started coming to the US in the 1960s mostly as tertiary students and visitors with the intention of making America their permanent home. Some also came as farm workers for production of sugar; they were skilled in sugar cultivation and ‘pan boiling’. The student or visitor visa was needed and the pretext for entry into the US, but once in the US, attendance in an educational institution was rarely pursued as most students lacked the financial resources. A few Indo-Caribbeans came to the US as early as the 1940s as students (Cheddi Jagan, Ranji Chandisingh, among others) and they returned to their country of birth after completing their studies. Those who came in the 1960s and later years, whether as students or as visitors or unskilled laborers on farms, or as professionals, or otherwise, did so with the intention of earning a living and making USA their permanent home; they were not returning to the land of their birth for the economic opportunities were limited. Some came with their families or kin. When they came to the US, they encountered nationals from India and other South Asian countries and ethnic Indians from other territories (like Kenya, South Africa, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, among others). Ethnic Indians stood (stand) out and easily recognizable because of physical outlook; their distinguishable features made them easily recognizable to Immigration Agents who were on the prowl to pick up and deport ‘illegals’ or students not fulfilling visa requirements.

In meeting or encountering a fellow ethnic Indian in USA up to the 1990s, one was excited because it was a rare occurrence; very few Indians were present in the USA during that period. Just a few thousands Indians from the Caribbean came to the USA during the 1960s as Indo-Caribbeans preferred UK, Holland, and France depending on their colonial mother country. When the UK granted independence to colonies, the mother country placed restrictions on immigration from the freed territories and Indo-Caribbeans began migrating to the USA and Canada. In 1965, the USA removed restrictions on nationals from India and other non-European countries. Indians were expressly prohibited from settling in USA pre-1965 although they were allowed in as students and visitors. But when the border was opened to them post 1965 to fill labor shortage caused by the Vietnam War, thousands of Indians (mostly professionals with a tertiary education) from India immigrated to the US with work permits and were quickly granted permanent residency. Indians from the Caribbean were not professionally equipped with the tertiary qualification to take advantage of work permits that were granted by US Immigration Department to meet shortage of labor. Indo-Caribbeans were largely deprived of a tertiary education in their home countries because of limited institutions and racial discrimination. Only a few (in nursing and accounting) had a post-secondary education to take advantage of US work permit rules to enter the USA; several Indo-Caribbeans took advantage of the labor law and migrated to the US. But the number of Indo-Caribbeans in the USA was small. It should be noted that the Indo-Caribbean presence in the Caribbean was relatively small of just about a quarter of the region’s ethnically mixed population of five millions (substantially less during the 1960s) and their migration numbers to the USA was also relatively small compared with their counterparts from India whose population in the 1960s was over 600 millions.

Relatively large numbers of Indians began arriving in the USA (through family sponsorships and with student and visitors’ visas) in the late 1970s mostly from India, Guyana, Trinidad, the Caribbean, Uganda and a few other countries in Africa and Asia. The number of Indians from the Caribbean was small relative to the numbers from India. The number of Indians in USA from Africa and from Singapore, Burma, Malaysia, Fiji, Mauritius was even much smaller (miniscule) and (Indo-Caribbean) encounters with them were very rare – mostly at a college campuses, or shopping at Indian stores, or at theaters that showed Indian (Bollywood) movies. Only a few thousands Indians came annually to the US from the Caribbean during the 1960s and 1970s and the numbers would ratchet up thereafter. Tens of thousands of Indians began coming annually in the late 1970s and 1980s especially from Guyana whose economy had collapsed by 1980. The number of Indo Caribbeans coming to the US thereafter substantially increased (as much as 20K) annually as economic situation in the region (Guyana especially) worsened.

Living in a strange environment, people were glad to meet someone from their own country and from their own district or village. Although they were all Indians, it was most difficult to identify whether someone was from Guyana or Trinidad or another Caribbean territory or from India or somewhere else from Asia or from Africa or elsewhere. Curiosity about one’s ethnic or national origin led to approaching each other and words of exchange. They wanted to know which part of their home country they were from. The Indo-Caribbeans and Indian nationals as well as Indians from elsewhere would meet at the work places, Indian shops, Bollywood cinemas, concerts featuring Bollywood artistes, Indian festivals, and chance encounters on the streets. Indo-Caribbeans patronized Indian movies at Columbia University, Bombay Cinema on 57th Street Manhattan, and elsewhere. Indian nationals opened the first set of Indian stores in Manhattan (around 23rd Street) where one can purchase Indian related items. Indians of all nationalities would meet there. Later, West Indian stores were opened in Manhattan also serving as meeting places for both groups.

Naturally, when two or more Indians happened to meet or had encounters in the US especially pre-1990s , the inevitable question was “where are you from” and if the response was from your home country the follow up question was “which part”? A friendly conversation followed and even an exchange of phone numbers – a friendly relationship may follow or remaining in contact. If from another country than yours, there was a friendly exchange and greetings and each went his or her way. If a Caribbean Indian encountered a national from India or the sub-continent the national from India or the sub-continent was curt or terse or unceremonious. The conversation or exchange was short. The national from India did not want to have a long exchange to inquire about the experience of the other or what life was like in their country or how they reached there or to offer advice or assistance on coping with life in America. The Indian national (from the sub-continent) did not display much excitement or welcoming feelings for the rare meet with an Indo-Caribbean and may even mistake the Caribbean Indian as a non-Indian (of some other ethnicity). It was not unusual to hear some said, “I thought you are Indian”.

In meeting another Indian, an Indian national would query ‘Which part of India you are from’? ‘What is your caste?’ If you were not from the same state, or spoke the same regional language, or from the same caste, Indian nationals kept a distance from you or those not of their group. Thus, they made short shrift of conversations or engagement with Indo-Caribbeans. Caste and regional territory have mattered to the nationals from India but not for those from the Caribbean. Caste had largely disappeared or did not matter in social or religious relations in the Caribbean by the end of the 1970s; inter-caste marriage was routine. Also, Indo-Caribbeans were marrying one another – Trinis, Guyanese, Jamaicans, Grenadians inter-married. Inter-religious marriage was also increasingly happening. Indo-Caribbeans saw all Indian nationals as one people. They do not know the difference or understand the distinction between a Gujarati or Sindhi or Uttar Pradeshi or other regional or language group. For Indo-Caribbeans, all Indians are one people. But in India, each group sees and considers the other differently. As opinion columnist and activist Vassan Ramracha once remarked, “We, the Indo-Caribbean people are the real Indians as we don’t have differences among us”.

When told that one was from Trinidad or Guyana or Grenada, it was not unusual for an Indian national to ask which state in India it was located. Or on first contact, it was not unusual for a national from India to ask which part of India are you from and when told Trinidad or Guyana, the follow up question was which state is it located. Their knowledge of international geography appeared limited. And when told, “I am not from India”, the follow up comment was “But you look Indian”. Seemingly, many Indian nationals were not very familiar that a few millions ethnic Indians live in the Caribbean – descendants of over half a million indentured laborers or girmityas who went to the Caribbean (British, Dutch, and French colonies) between 1838 and 1917 to work on plantations. Clearly, Indian girmitya history was not (and in fact is still not) taught in schools in India. India has neglected till now to teach aspects of her own colonial history in grade schools and college.

There are several explanation for the unwelcoming behavior of Indian nationals towards Indo-Caribbeans. One has to do with wealth, caste, and status. People who came from India were rich and perhaps college ‘educated’ – with many having servants. In India, the rich tend to live a sheltered life away from the lower classes and people of different castes. Indian nationals strongly embraced a class and caste system and treated others accordingly. They socialized among their own. They were socially conditioned by wealth and caste. Wealth and caste determined social status and hierarchy even at colleges where one expected a different behavior based on social equality. Their wealth and high caste made them feel superior to others who were not of equal status or same caste. They saw others, especially from the Caribbean who crossed the Kala Pani, as inferior because they lost their caste. Indo-Caribbeans were not wealthy and most were from the lower class or lower echelons of their home countries escaping racism, persecution, and poverty. Thus, they were treated as inferior.

Another factor that partly explains the behavior of Indian nationals towards Indo-Caribbeans is communicating in an Indian language. Indo-Caribbeans were not versed in Indian languages having lost their mother tongue (Hindi, Bhojpuri, Tamil). Thus, Indian nationals did not feel an affinity for them. At social gatherings, Indian nationals communicate in their native tongue making conversations or engagements between them and Indo-Caribbeans almost impossible. They tend to look down upon other Indians who don’t speak their language. Indo-Caribbeans speak English or its dialects.

Two other factors explain the behavior of Indian nationals towards Indo-Caribbeans. Observed among Indian nationals was palpable feeling of guilt of not displaying nationalism towards India like that of Indo-Caribbeans and of jealousy of Indo-Caribbeans in retaining their identity and celebrating Indian festivals. There was an element of jealousy displayed by Indian nationals that the Indo-Caribbeans held on to their identity (and have done so for over 185 years away from Mother India). The Indo-Caribbeans have been very proud of their identity and of India flying the Indian flag at their cultural functions and in their homes. Indo-Caribbeans are very patriotic and in fact more nationalistic towards India than some Indian nationals and many (those who have not converted to Christianity) are very Hindu oriented worshipping India in their prayers as a deity. The Indian Caribbeans, right after their arrival in America in the 1960s, established temples in apartments and hotel rooms and later houses to conduct religious services (Hindu). Islamic services were also held by Muslims in apartments and rented halls. The Indo-Caribbeans celebrated Indian festivals long before Indian nationals started holding public celebrations of their national days and religious festivals. Indo-Caribbeans feel the observance of religious festivals was a source of jealousy. Indo-Caribbeans initially practiced their faiths in hotel rooms and apartments and then in houses that were transformed into temples. They celebrated Phagwah, Diwali, Navratri. Janamashtmi, etc. in private gatherings in temples that were regularly patronized by nationals from India. There are dozens of temples among Indo-Caribbeans. Indo-Caribbeans shared their temples with and invited Indian nationals to their religious services and celebration of festivals including celebrating India’s independence. Indo-Caribbean Hindus are deeply ingrained in their ancestral culture. Indian nationals may have felt belittled or insulted that Indo-Caribbeans, who don’t even speak the Mother tongue or the language of the scriptures, are ‘more religious’ than them. The Indian nationals, after founding their temples, were not very comfortable ‘in sharing’ their temples with Indo-Caribbeans.

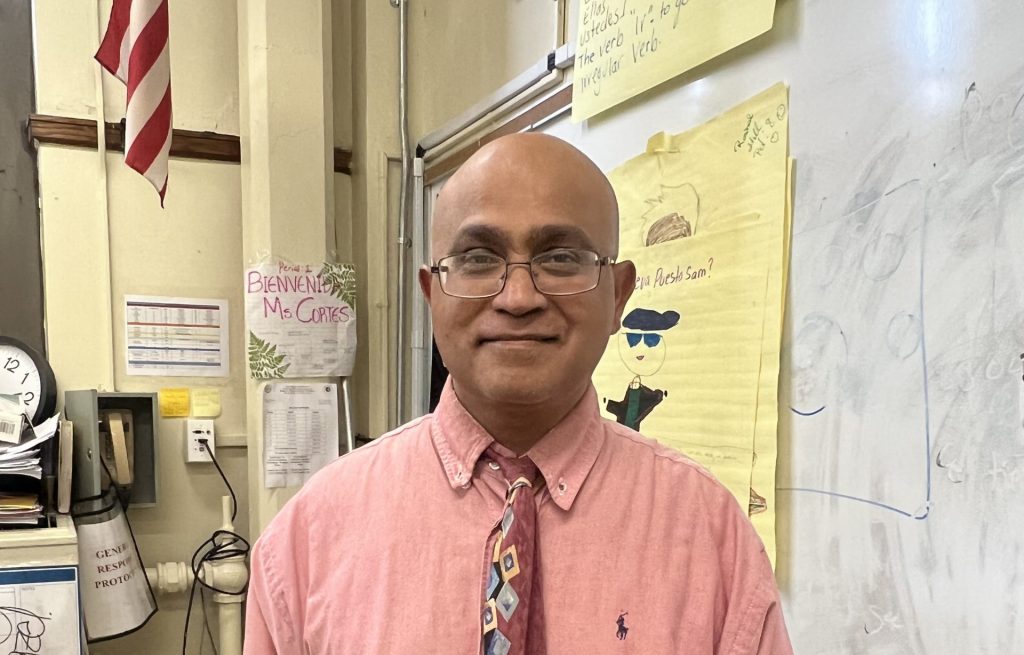

Not all encounters between nationals from India (and other countries) and Indo-Caribbeans were unfriendly or unwelcoming. Some of the encounters were very warm, cordial, respectful, and long lasting. Some nationals were sympathetic with Indo-Caribbeans having learned about their problems, difficulties, and challenges the Indo-Caribbeans experienced in America and the Caribbean. Some were and still are most impressed with Indo-Caribbeans for their cultural retention and the pride they took (take) in their ethnic Indian identity and for holding on to ancient religious belief. They showered accolades on the Indo-Caribbeans. Understandably, the Indian nationals in the early encounters didn’t know much about Indo Caribbeans, their experience and challenges, and their way of life. A few Indo-Caribbeans, including this writer, Baytoram Ramharack, Vassan Ramracha, and a few others engaged prominent Indian nationals since 1977 to cement ties and cooperate to address challenges facing Indian immigrants in America. Meetings were hosted at City College, Kali’s office in Jamaica, restaurants in Manhattan and other locations through the Indo Students Club of CCNY that was founded by a group of Indo-Caribbeans (including this writer). Lectures by Indian Professors were hosted at City College allowing for greater understanding of each group and deepening relations. Many encounters between Indo-Caribbeans and Indian nationals occurred at City College campus and at other campuses (Baruch, Hunter, Brooklyn, Lehman, and NYU) between 1978 and the end of the 1980s initiated, planned, and organized by Baytoram Ramharack, Vassan Ramracha, and myself). Once they became familiar with Indo-Caribbeans way of life, the attitude of India nationals towards the group gradually changed – there are several inter-marriages. It would take a couple of decades of encounters (1960s thru 1980s) for the Indian nationals to understand and appreciate who the Indo-Caribbean people are, how and why they ended up in the Caribbean, and the difficulties they faced. The groups began have a better understanding of each and closer relations in 1988 through the work of Indian Diaspora Committee that organized a week long commemorative activities for the 150th Anniversary of the Indian presence in the Caribbean at Columbia University and the work of GOPIO that organized the first global convention of people of Indian origin, a week-long get together that was held in Manhattan in July 1989 at the Sheraton Convention Center. This writer was one of the main organizers of the Columbia University conference and served as host of organizers of the global convention of Indians. Well known community advocate and newspaper columnist Ravi Dev, community organizer Ramesh Kalicharran, and myself, all Indo-Caribbeans, played important roles in planning and organizing the global convention. The two sides engaged each other at both conferences and became gradually closer thereafter. Credit is given to well known Guyanese American businessman Ramesh Kalicharran (Kali) for his unrelenting work serving as a liaison helping to bridge the connection between the two groups. Kali was/is well known in both communities hosting meetings since early 1980s at his office to plan joint events. He was a prominent face at India festivals and a promoter and financial sponsor of events. His advertisements featured prominently in magazines and newspapers published by Indian nationals. Two other prominent Indo-Caribbeans who worked closely in trying to build connections with Indian nationals were/are Deo Gosine (from early 1980s) and Ashook Ramsarran (late 1990s). An Indian national who worked very closely with Indo-Caribbeans was Yash Pal Soi. He admired Indo-Caribbeans for retaining their cultural identity and treated them with respect and deference. There were also a few others like Jagat Motwani (an author), Brij Lall (Bharat Vani Radio from Fordham Univ), and Dr Banad Vishwanath who pioneered the first Indian TV program on WNJU TV, among others.

The Indian nationals were not to be wholly blamed or be responsible for their cold behavior towards and restrained engagement with Indo-Caribbeans. They were/are largely ignorant of their own history as a people. They did not know that Indians were taken and settled outside of India in Africa, the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, Pacific, and elsewhere since the early 1800s. The history of Indian migration was not a mandatory subject taught in grade schools or colleges in India. Thus, they would not have known about the Indo-Caribbean existence. Also, India has had regional and language loyalty rather than all India nationalism. The Indian nationals encountered by Indo-Caribbean during the early years (1960s thru 1980s) were Gujaratis, Punjabis, Sindhis, Kashmiris, Rajasthanis, Tamils, Keralities, Andhras, Telugus, Marathas and others from the South who had/have little in common with Northerners from the Hindi/Bhojpuri speaking and cultural belt. Indo-Caribbeans were mostly from the Hindi/Bhojpuri speaking belt. Thus, most Indian nationals encountered in Europe and North America had/have little affinity with Indo-Caribbeans and partly explained their cold shoulders towards the latter. They did not know of the trials and tribulations of Indo-Caribbeans in the Caribbean or in North America and Europe and as such could not relate with or understand them. Also, one must take into consideration that both groups have different lived experiences and therefore would behave differently towards each other in encounters. Although they have a common more – same motherland — they saw and experience the world differently and it was expected they would view and behave differently towards each other. It is noted that although the two groups did not share much commonality or close connections, the Indian nationals assisted with the Indo-Caribbean struggle in America for restoration of democracy in Guyana.

The relationship between Indian nationals and Indo-Caribbeans is slowly changing and with time the Indian nationals will more closely relate to and affiliate with the Caribbean Indians especially that the latter is growing in size approaching a million.