Between 1838 and 1917, East Indians were recruited and brought to Guyana, then a British colony called British Guiana, under the Indentureship scheme to provide manual labour on the sugar plantations, almost all in the hands of British and Scottish owners. Through this system, an overseas individual was contracted to work on a specific plantation for a fixed period of time under stated terms and conditions, including a fixed wage rate. East Indians were not the first or only group of labourers recruited under this arrangement. However, most of the non-Indian immigrants withdrew from the plantations soon after their introduction, and by the early 1850s, India became the primary source. According to the British Guiana 1924 British Empire Wembly Exhibition report, of the 343,019 immigrants recruited between 1835 and 1921, India provided 239,979. Subsequent studies have indicated that around 75,800 of the Indians returned to their homeland and the rest remained as settlers. A 1959 study by Raymond T. Smith (Some social characteristics of Indian immigrants to British Guiana, Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 13:1, 34-39+ ) shows the religious affiliations of the East Indian immigrants as follows: 83.6 percent Hindu, 16.3 percent Muslim, and about 0.1 percent Christian.

For centuries, beginning with the Inter Caetera, the Papal Bull (Papal decree) of Pope Alexander VI in 1493, the Catholic rulers of Spain and Portugal were authorized to claim non-christian lands discovered by their navigators and convert the inhabitants, termed “heathens”, to Christianity. The decree granted Spain the rights to the Americas and Portugal the rights to Africa, Asia and Australia. Indians, as part of the Asian continent, were thus labelled and targeted for conversion. Subsequently, during the rule of India by the East India Company of Britain, crusade in Britain by the Clapham Sect, an Evangelical Christian group, led to passage in the British Parliament of the Charter Act of 1813 (known as the East India Company Act of 1813) with specific provision for Christian missionaries to enter India and engage in religious proselytization. In 1830 Scottish Reverend Alexander Duff entered India as the first overseas missionary of the Church of Scotland and had profound effect on the Indian education system. According to Wikipedia, he devised the policy of “using a western system of education to slowly convert Hindus and Muslims to Christianity…In 1844, governor-general Viscount Hardinge opened government appointments to all who had studied in institutions similar to Duff’s institution”. In 1844 Reverend Duff toured Canada and in every major city addressed audiences on the need for foreign evangelism. His message spurred Canadian missionary activity abroad and his approach in India of using education to gain converts was adopted by Canadian Presbyterian Reverend John Morton in his Mission in Trinidad. The Trinidad model was later adopted in Guyana.

In Guyana, from around 1852 when it became apparent that the Indentureship scheme was firmly established and many Indians were choosing to remain in the colony, some of the established Christian churches commenced attempts to convert the indentured Hindus and Muslims. However these attempts were unsuccessful as noted by Reverend H.P.V. Bronkhurst, a Wesleyan Methodist minister who arrived in 1861 to work among the East Indians. In his 1876 report to the mission board in England, he stated that between 1876 and 1881, the church membership of Indians was as follows: 48, 47, 38, 43, and 45.

In 1880 Reverend John Morton who was heading the Canadian Mission (CM) in Trinidad, a Branch of the International arm of the Canadian Presbyterian Church, came to Guyana at the invitation of Reverend Thomas Slater of the Scottish Presbyterian Church to review and offer advice on how the Church could bring the indentured Indians into their fold. After reviewing the situation Reverend Morton wrote to the Canadian Presbyterian Church and recommended that they establish a CM body in Guyana. In his Master’s thesis to Queen’s University on the Canadian Presbyterian Mission in Guyana, Alexander Dunn notes that Reverend Morton, in his recommendation to the Canadian Presbyterian Church for a mission in Guyana, states “The Canadian church should push on to do something for the 60,000 to 70,000 Heathens there”.

The push for the entry of the Canadian Presbyterian Church into Guyana came from Reverend Thomas Slater, Scottish Presbyterian Minister of St Andrews Kirk, Georgetown, 1864-1887, and Alexander Crum-Ewing, absentee Scottish owner of sugar plantations in Guyana at the time. Following a request by Reverend Slater to the Canadian Presbyterian Church in 1883 via the Trinidad Mission, Reverend John Gibson arrived in July 1885 after his appointment in Toronto and a year of training in Hindi at the Trinidad Mission. However, as his work in the West Coast of Demerara was beginning to have an impact, he contracted yellow fever and died in 1888. By then Alexander Crum-Ewing was seeking a Minister for the church, manse and school he had erected in 1868 on his plantation at Better Hope, East Coast Demerara where Reverend Slater in old age and poor health was ministering on an interim basis after retiring earlier from St Andrews. In response to a request from Crum-Ewing, James Basnett Cropper, a graduate of Pine Hill Seminary, Halifax, Nova Scotia was appointed and arrived in 1896.

James Cropper was the right person at the right time for the appointment. He was the son of Mr R. P. Cropper, Protector of East Indians in St Lucia. There as chief clerk to the Governor he had worked among the East Indians, learned to speak Hindi fluently, and started Presbyterian work among them. Prior to going to Halifax for study inTheology, he had taken over Reverend Morton’s field in Trinidad while the latter was on furlough and was highly commended for his work. He arrived in Guyana at the time when the Government was making its third attempt at

inducing the immigrants to forego their rights to return passages to India in lieu for land and become permanent settlers in Guyana. Shortly thereafter Indians villages started to develop along the coast and along the banks of the Mahaica and Mahaicony rivers. These developments provided the opportunity to establish churches/schools in these areas and Cropper grasped the chance to act. He even served as Superintendent of Settlements for a few years, thereby enhancing his position with the Church and the immigrants.

Nova Scotia in the 1940s, and provided by her daughter Mary Schofield.)

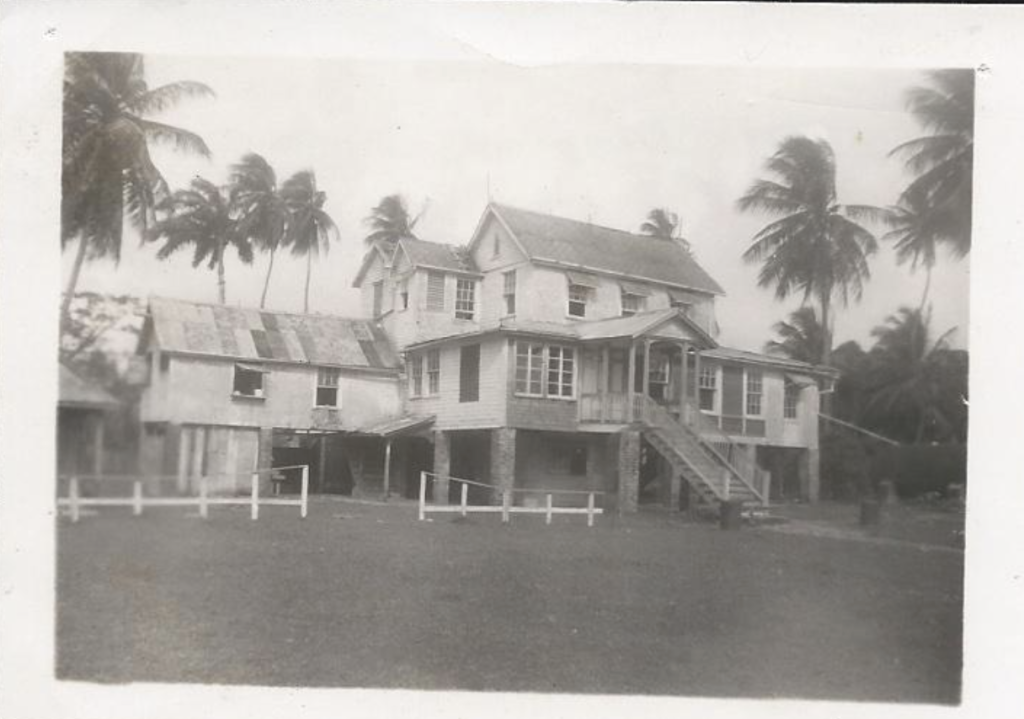

Over the years until his retirement in 1935 he headed the Canadian Mission, the name ascribed to the Canadian Presbyterian Church in Guyana. He together with other Canadian Presbyterian missionaries in the country worked assiduously to establish the Church in Guyana among the East Indians. Two of his key lieutenants were Reverend Gibson Fisher and Reverend James Scrimgeour. In 1903 Reverend J. D. Mackay arrived and went to work in Essequibo where he was making good progress but disaster occurred in 1905 when he drowned on way to Wakenaam. Gibson Fisher, an English Methodist minister in Essequibo then joined the Canadian Mission and took control of the Essequibo region. Fisher proceeded to use Mission funds to purchase a large house in Johana Cecilia, previously owned by a judge, which became known as the Sarnia Manse. In addition to being his residence, it housed catechists on weekends for training sessions and was the home of youth volunteers from Canada. Reverend Fisher extended the mission in Essequibo and passed away in 1933. The Fisher Government (formerly Gibson Fisher Canadian Mission) School in Golden Fleece, Essequibo was named in his memory.

Reverend Scrimgeour arrived in 1912 after spending three years at the Mission in Trinidad and was assigned to the Berbice region, previously managed in addition to Demerara, by Reverend Cropper. He saw the need for a High School and in 1916 set up the Berbice High School for boys in the lower flat of his residence in New Amsterdam. He wanted the school to produce a better boy for Guyana even if he remained a Hindu or a Muslim. This was contrary to the view of Cropper who felt strongly that “education must be secondary to the all important work of soul saving in Evangelical work”. In 1920 the Berbice High School for girls was opened in a separate building. Decades later the two schools were merged and became co-educational. In 1927 after a split in the parent Church in Canada Reverend Scrimgeour returned to Canada. Of his departure Cropper remarked that his loss was the greatest blow the Mission had ever suffered.

As for Cropper himself, in an article “Christian History of East Indians of Guyana” Clifmond Shameerudeen, citing Alexander Dunn, writes “ Cropper was well received and respected by the East Indians. His celibacy and long white beard earned him a title given only to holy men. He was called a sadhu, which earned him respect and permission to be a teacher among the East Indians. He was also given the nickname sahib, a father figure title in the culture of East Indians. This demonstrates that he was seen as a person of maturity and authority. In essence, Cropper became an insider among the East Indians rather than just a foreign white missionary”. The Cropper Government (formerly Canadian Mission) School in Albion Front, Berbice was named in his memory.

The Canadian Mission, like the other churches that were attempting to evangelize the East Indians, relied on Indian catechists, to reach out to the Indian immigrants. Often, these catechists were recent converts to Christianity whose mother tongue was Hindi and they were the go-between the missionaries and the immigrants. They were responsible for visiting homes and hospitals, giving religious instruction in the Mission’s schools, teaching Sunday school, conducting services, holding outdoor evangelistic meetings, and teaching reading at nights. A catechist received around ten dollars per month for his work and was expected to augment his earnings by growing his own rice and vegetables. According to Dunn, these workers received weekly training in areas such as “comparative religions, Bible subjects and English. Such training prepared them for debates with their fellow Indians who remained Hindus or Muslims and they were generally aggressive or at times even belligerent in deference of their new faith.

The overriding business of the Canadian Mission in Guyana was the evangelism of the Indian immigrants and the missionaries worked exclusively among them. As Hindus were the overwhelming majority and also because Muslims with their monotheistic belief proved more difficult to evangelize, many Hindu terminology, concepts and practices were adopted and used to gain Hindu converts. An early Canadian Presbyterian Church on the Essequibo Coast is called Akashwani (Voice from Heaven) and another on the Corentyne coast is called Mukti Bhawan (House for liberation of the soul). A Christian prayer was called “prarthana” (equated to a Hindu prayer) and a hymn was called a “bhajan” (equated to a Hindu devotional song). Jesus Christ, called “Yesu Masih” was communicated by the catechists as an incarnation of Hindu “Ishvara” (God as a person). The “Katha”, a Hindu prayer service with reading of excerpts from a Hindu holy book was adopted in the form of “Yesu (Jesus) Katha”. Not only was the story of Jesus communicated in a similar fashion but it was followed likewise by distribution of Indian sweets called “Prasad” (food first offered to a deity then distributed to followers). Also, the story of Jesus was written in Hindi poetry of “doha” (couplets) and “chowpai” (quatrain), patterned after the Hindu Holy book, The Ramayana, and sung in the same manner. At times too, preachers used sections of the other Hindu holy book, The Bhagavad Gita, to support their claim that Jesus Christ was an avatar of Brahma (Hindu God in his role as Creator).

Cropper retired in 1936 and by then the Church passed into the hands of other Missionaries from Canada. However, local leaders were emerging who eventually gained control as the Church evolved into the Guyana Presbyterian Church. While the number of converts remained relatively small, the greatest achievement was in the area of Indian education. The majority of Indian children in the colony were educated in primary schools which until 1961 were operated under the Canadian Mission banner and by then Berbice High School was one of the top four secondary schools in the country.

Alexander Dunn, whose father was one of the Canadian Missionaries to then British Guiana and who grew-up in the colony in the 1930s and 1940s, reflects the collective feeling of the missionaries when he notes “It grieved the early missionaries to see these children growing up ignorant and illiterate and they felt that the children must be educated in East Indian schools. Part of what was taught, of course, was the Christian religion so that children who attended Canadian Mission schools might be won for Christ. The missionaries also reasoned that they might win the parents to the path by what they were doing for the children.” Irrespective of the motivation of the missionaries, Indian-Guyanese owe a debt of gratitude to these dedicated souls, many of whom suffered extreme hardship, disease and death, for educating their ancestors and laying the foundation for their success in the now independent Guyana.