Our heritage is lacking!

by Albert Baldeo

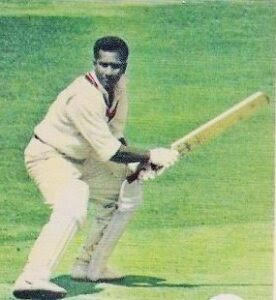

“No more technically correct batsman ever came out of the West Indies than Rohan Kanhai” – Michael Manley

“To see Kanhai flat on his back – with the ball among the crowd beyond the square-leg boundary – after making one of his outrageous sweeps to a good length ball, is to watch a man capable of playing shots fit to lay before an audience of emperors” – James Scott, May 1966, on the occasion of Guyana’s Independence

“Kanhai discovered, created a new dimension in batting…He had found his way into regions Bradman never knew.” – CLR James

“Some batsmen play brilliantly sometimes and at ordinary times they go ahead as usual. That one… is different from all of them. On certain days, before he goes into the wicket, he makes up his mind to let them have it. And once he is that way nothing on earth can stop him. Some of his colleagues in the pavilion who have played with him for years have seen strokes that they have never seen before: from him or anybody else” – Sir Learie Constantine to CLR James, on Kanhai

“Rohan Kanhai was a great player…and he was rated one of the tops…a good cricket brain…earned the respect of his players.” – Sir Garfield Sobers.

Rohan Kanhai, is still batting 90 not out on Boxing Day. Like Cheddi Jagan, and many others, he shone for us, and for freedom, independence and dignity! We must name a street, stadium and/or drive after Rohan Babulall Kanhai now! Give Kanhai his due, because his strokes were light years ahead of any other, as he became the embodiment of dominance, pride, and fearless self-belief. Kanhai reminded us that cricket, at its finest, is more than a sport—it is an art form where talent, temperament, and timing blend into something magical. The finest innings transcend national rivalries and statistical milestones, leaving an imprint on the hearts of those who witness them, and his innings were pure, like Guyana’s gold.

No batsman has ever dominated with such original splendor, nor in such sublime fashion. He was romantically enthralling, imperious and flamboyantly gifted, and his shot selection bore the hallmark of thrilling improvisation, classic stroke play and exalted quality that can only come from a man blessed with genius and divine gifts–and knew it. There simply was no shot he could not play, or invent, dictated by his mood at that time. A vintage Kanhai had no equals. In the most popular version of the game, T20, many pretenders have tried to reproduce his unique triumphant falling hook, but none have equalled the rapture and success his inventive stroke added to the dimensions of batting decades before T20 came into existence. Factor in the fact that Kanhai never batted with a helmet, and his conquests over a hurtling 100 mph leather ball that have ended the lives of other cricketers, takes on deep perspective.

When he was bored, he could throw his wicket away with disinterest, but when he was challenged, he would enter new zones of batsmanship, and no bowler, alive or dead, could escape his genius. The attendant unpredictability is best explained by Ian McDonald, “This explains the waywardness and strange unorthodoxies that always accompany great genius.”

My memory goes back to 1974. My father took us to Bourda to see Rohan Kanhai bat. He was 10 not out overnight against England. He was, most likely, playing his last test innings. He was 39 years old then, totally grey. Dad wanted us to remember our champion who was memorialized globally, and romanticized in folklore. I thank my father to this day for that privilege.

He made 44, before Derek Underwood spun one past his defense on a wet wicket, but I had seen enough of the man to appreciate his genius. A batsman’s pedigree lies in the quality of his strokes, and in that brief innings, Kanhai played some trademark shots. He hooked, pulled, late cut, cover drove and slashed magnificently, enough to saturate the soul that he was blessed with bountiful talents. He floated off the front and back foot like a ballerina, dropping the ball dead when he defended.

His style was unforgettable, and he added silken grace to it. When Chris Old and Tony Grieg bounced to him, the bat sprang like a cobra, meeting fire with fire. Never ducking or running. He gave us 2 late cuts which he delicately curved past a hapless Amiss en route to the boundary. A half cut, half drive past cover sped like a laser beam to the boundary, a parting gift to the crowd. Yes, I saw him-Kanhai, the ultimate epitome of elegance and power combined. Underwood said later that was the best ball he ever bowled.

He was our boyhood hero, and was undoubtedly the most extraordinary batsman the West Indies has ever produced, blessed with such natural ability that he could eviscerate any bowling attack in the world when he controlled the impetuosities that raged within him. There was beauty in his craft, so much different in his method of annihilation, especially on the treacherous, uncovered wickets in his day. Clinical precision over poetry. Ballet over dance. Artistry over bludgeon. He glided in riveting stroke play, batting with the dexterity of a virtuoso, yet prone to Shakespearian tragedy at any time. Kanhai on the rampage was a mesmeric joy to behold, even for bowlers. And he was the national pride of Guyana, giving meaning to our new found Independence.

Michael Manley, the former Prime Minister of Jamaica, said it best, “The West Indies are Third World countries, but we belong, and are, in the First World of Cricket.” Although cricket’s champions have declined appreciably, Manley defined what cricket supremacy means in a global context to the average Caribbean person. Cricket is not only a religion in the Caribbean, but its glorious, collective history best defines the unifying factor and pride in the region, far outpacing regional political integration.

Collaterally, his interaction with the game of cricket spawned changes to the socio-political structures of society and made him a hero figure for generations to emulate. Whether it was cricket or any other endeavor, Kanhai imbued in his countrymen the passion “never to be one for second best,” as he so eloquently wrote in his memoir, “Blasting For Runs.”

Whereas he did not attain superstar status or pile up gigantic statistics like others situated above him in figures, like Sir Don Bradman, Brian Lara, Sachin Tendulkar, Kanhai possessed a unique combination of batting prowess, originality and sportsmanship that has never been seen in the game of cricket and perhaps, will never be seen again.

His creative genius surpassed any other batsman in the game, and his flamboyance was spellbinding, which enabled his artistry to attain heights of batsmanship beyond the reach of any batsman, such as in the execution of his unique “triumphant fall,” or falling hook shot, most times played off the eyebrows, the half-pull, half-sweep style maneuver, the effortless flick off the toes which dissected the on-side field, the reverse sweep off the middle stump, the magical late-cut or his majestic cover driving.

Cricketers like him invented and pioneered many innovations to the game, which have made it richer and dearer to spectators. Many batsmen may enter the same cathedral of batsmanship with Kanhai, but will not be allowed to sit in the same pew. In Michael Manley’s book, “A History of West Indian cricket,” Kanhai is photographed sitting with George Headley and Everton Weekes, and that is how they may all sit in the front pew of that West Indian proverbial cathedral, alongside knights Viv Richards, Gary Sobers, Frank Worrell, and Brian Lara. However, in terms of originality, artistry and creative skill, Kanhai stands alone.

In his book “Idols,” Sunil Gavaskar, whose gigantic batting feats have not only eulogized him in calypso, but also immortalized him in a manner second to none, said this of Kanhai: “Rohan Kanhai is quite simply the greatest batsman I have ever seen. What does one write about one’s hero, one’s idol, one for whom there is so much admiration? To say that he is the greatest batsman I have ever seen so far is to put it mildly. A controversial statement perhaps, considering that there have been so many outstanding batsmen, and some great batsmen that I have played with and against. But, having seen them all, there is no doubt in my mind that Rohan Kanhai was quite simply the best of them all.”

Gavaskar concludes, “Sir Gary Sobers came quite close to being the best batsman, but he was the greatest cricketer ever, and could do just about anything. But as a batsman, I thought Rohan Kanhai was just a little bit better.” In his book “Living For Cricket,” Sir Clive Lloyd definitively said that he regarded Kanhai as “the finest batsman Guyana has produced.” Richie Benaud, one of the most respected cricketers and commentators, in his autobiography, “Willow Patterns,” confirmed that he “thought that Kanhai was just a shade over Sobers.”

Kanhai’s greatness lies to a great degree with his connection to history, and the way he overcame the social and political forces of British imperialism which subdued him and his countrymen in his time. His courage, exploits and art became a national call to action. A captivating player, he lifted and carried the hopes and aspirations of the Caribbean people during a period of political deprivation in their collective history, where his sweet successes or bitter failures mirrored theirs during the shackles of colonialism. He became a symbol of hope, glorious expression and unrestrained freedom. We felt that we, too, could conquer, like him!

When C. L. R. James wrote in the New World journal that Kanhai was “the high peak of West Indian cricketing development,” it is one of the greatest tributes paid to any West Indian hero, and focuses on the creativity Kanhai brought to cricket, and how he inspired others to do likewise. James saw in Kanhai’s batting the embodiment of potential “bursting at every seam” from a post-colonial society, and reminded the world that Kanhai’s brilliance served as a powerful counter-narrative, demonstrating that a player of East Indian descent could achieve the highest levels of sporting excellence and represent the entire West Indies. Kanhai not only blasted thunder balls, but he also smashed granite ceilings, hence the sobriquet Corentyne Thunder!

Guyana celebrated when The Lall shone, brooded when he failed. In my boyhood days, he inspired youngsters like me to think that, like him, we too, could one day achieve international fame. With his showmanship and range of breathtaking strokes, few batsmen will ever attain the idolatry and heroism of Kanhai. He was a born favorite, blessed with the fearless heart of a lion. His conquests of great bowlers such as Lillee, Thompson, Gupte, Trueman, Statham, Lock, Davidson, Mahmood, and others are legendary. When Charlie Griffith rocked back his stumps first ball with a no ball, he cut loose into both Hall and Griffith at Bridgetown during the Shell Shield mini test between Guyana and Barbados, and smashed them all over Kensington fearlessly for a brilliant 108 with 17 boundaries. Joe Solomon said it was the best century he ever saw, a clinical expose.

Although one never to chase after batting records, Kanhai nevertheless achieved an impressive array of memorable milestones. For example, although Tendulkar is the modern icon of batsmanship, he has never scored a test century in each innings of a test match as Kanhai magnificently did against as worthy an opponent as Australia, at Adelaide in 1960-61, nor top the batting averages in an English season as he did in 1975 with an average of 82.53 as he destroyed all and sundry, nor share in such high-wicket partnerships in first-class cricket as he did with J.A. Jameson-465*, Warwickshire v. Gloucestershire, 1974, second wicket and with K. Ibadulla-402, Warwickshire v. Notts, 1968, fourth wicket.

And who would not help but admire his one-day average of 55 runs per innings? Or, notwithstanding the fact that statistics were always the furthest thing from his mind, appreciate that he scored 83 first-class centuries, and countless 90s, each innings a spectator’s dream? One must never forget that Rohan was one the best fielders in the world in his heyday, and a sportsman and gentleman who would recall a batsman to continue his innings when he felt that the umpire had given him out incorrectly.

Rohan blasted open the doors for others to follow. In fact, Gavaskar, Kallicharran and Bob Marley named their sons after Rohan Kanhai, and many West Indians all over the Caribbean are named after him, a testimony to Kanhai’s greatness. Gavaskar also hoped that his son Rohan would be at least half as good as the original Rohan Babulal Kanhai, which he said would make him very proud indeed! We will never see his like again.

Long after the stumps have been drawn, the applause has died, and the Bourda stand bearing Rohan Kanhai’s image has fallen to dust, we must honor the memory of this great Guyanese pioneer and hero, with a lasting monument and throughway dedicated to him, that capture his magnificent and unprecedented flight of courage, genius and nationhood. Collectively, we will continue to fail our heritage in not doing so immediately. As Dave Martin, another Guyanese legend, asked, “Where are our heroes, Guyana?”

Hon. Albert Baldeo is the 1st Caribbean, South Asian elected District Leader of Richmond Hill, Little Guyana/Caribbean/India, NY, USA, President of the Richmond Hill Democratic Club, Asian American Labor Alliance, Chairman of the Liberty Justice Center and Baldeo Foundation, a community organization dedicated to the fight for community improvement, justice, equal rights, public safety, dignity and inclusion in the decision-making process.