Dear Editor,

On June 20th 2024, I was honoured to be invited to a special concert commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Diplomatic Relations between Trinidad and Tobago and China. This concert was held at the National Academy for the Performing Arts in Port of Spain and featured the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra, the National Steel Symphony Orchestra of Trinidad and Tobago and the National Philharmonic Orchestra of Trinidad and Tobago, who all performed individually and collaboratively to create an absolutely sublime tribute to both nations. It was especially astounding to witness the melange of traditional Chinese instruments playing harmonically with both Western instruments and especially the steelpan to create fantastic interpretations of existing melodies. All in all, the event was fascinating and exhilarating and served as a wonderful example of how different styles and techniques can often complement each other in new and exciting ways to create unique compositions that would not have been possible otherwise.

That having been said, seeing how well traditional Chinese instruments, such as the erhu, the bamboo flute, the ruan and the sheng, were able to integrate with both our Philharmonic and Steel Symphony Orchestras, raises the question of why there was no attempt to integrate with local East Indian musicians and musical instruments in the same way. If this truly was a showcase of all that Trinidad and Tobago has to offer musically, is it not somewhat strange that there was absolutely no recognition of the contributions that East Indian culture has had in the development of music throughout our Independence? Of course, it cannot be strange because this is not the only national venue that completely ignores the value of East Indian accompaniments and the fact that no one has taken notice is more evidence of the ingrained aversion to this subsect of Trinbagonian culture that has been allowed to continue to exist.

In a recent conversation with someone I was explaining that despite the growing popularity of Chutney and Chutney Soca, especially during the Carnival season, there has never been a showcase for this music in either the Dimanche Gras or even as a serious contender to the Road March competition. But it also occurred to me afterwards that a more fitting venue for the display of East Indian culture might have been the Independence Day parade, but not a single national band has ever thought to include their instruments into their routine. Imagine how impactful a message it might have sent had a single marching band replaced the more traditional snare for a tassa drum instead. Because not only would it demonstrate the inclusivity that so many people have been longing for, but also it would have been a better signal of progression after Independence that we are forging our way forward with our own hands, and not holding on to the tools that were left for us by our Colonial masters.

Right now, we are at a seminal moment in the history of this country, and despite how some might feel on the matter, this is one of the most important issues for our people at this time. This matter is no less significant than when President Ellis Clarke had his staff scramble to locate a Bhagavad Gita for Basdeo Panday to be sworn in as a Government Minister in 1986; or when Pundit Krishna Maharaj refused the highest award of our nation because it was still called the Trinity Cross in 1995, which prompted both Sat Maharaj and Inshan Ishmael to challenge its legitimacy in the court that ruled that this Christian symbol was in fact discriminatory. The continued disregard for the contribution of East Indians to the development of this nation cannot be allowed to continue, lest future generations become ignorant of these facts.

The final thing I want to say on this issue is that, in terms of symbolism, everything that was included in the current Coats of Arms is representative of something ethereal rather than just an image in and of itself. The coconut palm reflects the THA; the helm represents the British Monarchy; the boats represent European discovery and colonization, the hummingbirds represent the Indigenous tribes and their name for Iere; and the mountains represent the erasure of those natives and the renaming of Trinidad by Columbus. Even the Scarlet Ibis and the Cocrico are symbols of the unity of both islands coming together and the watchwords are our aspirations for the future. As such, the inclusion of the steelpan will undoubtedly represent the struggle and rebellion of the African slaves and workers on the plantations; and that is why the inclusion of the tassa drum becomes important because it reflects the contributions of East Indians to this country over the years, and that is what is being refused if it is left out. While some might suggest that this can be included later on by a different administration, need I remind you of that time when a misinterpreted image on the previous $50 bill created pandamonium in certain circles? The best time, and really the only time, it can be done is together with the steelpan, and symbolically, it also makes the most logical sense. But for East Indians to be ignored again at this moment, will send an even greater message than should it be included.

Best regards,

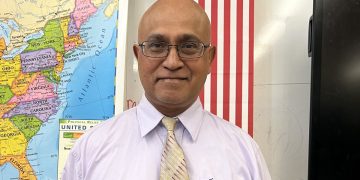

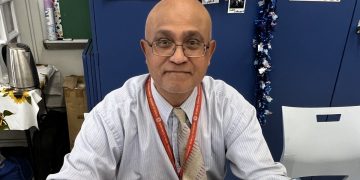

Ravi Balgobin Maharaj