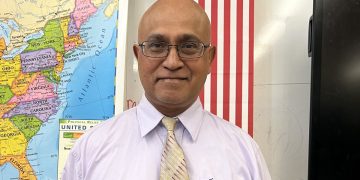

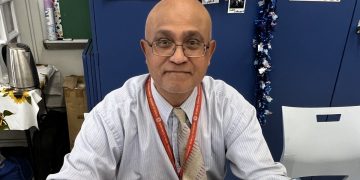

The difficulty in analyzing “racism” or “ethnicization” can be illustrated in a recent debate on the sugar industry. Attorney General, Hon Anil Nandlall, expressed shock over Opposition MP, Mr. Khemraj Ramjattan’s statement that the decision by the PPPC government to re-open the three (3) closed sugar estates was racist. Mr. Nandlall responded tersely: “if the decision to re-open the sugar estates was a racist one, then logically the APNU-AFC’s decision to close them was also racist.”

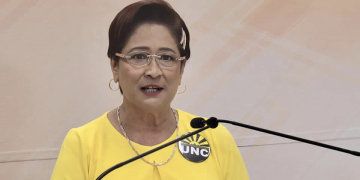

Two politicians view the same problem of the sugar industry-which employs an overwhelming majority of Indo-Guyanese- with different lens: Mr. Ramjattan asserts that racism drove the government policy to reopen the sugar estates, while Mr. Nandall justifies it on economic grounds. Mr. Ramjattan believes that the sugar industry is not financially viable, given the heavy losses it incurred since 2012, and therefore concludes that the rationale for re-opening the estates has to be racist and not economic. Contrary to Ramjattan’s view, that was a “political and not a racial decision since the PPPC government is not seeking to oppress other groups,” notes Ravi Dev.

The PPPC government has also proffered a plethora of other economic reasons for their sugar policy. Given the historic and formidable connection between sugar and the economy (supporting other activities/programs: sports, healthcare, housing, drainage, and irrigation) to spend less than 5% of the country’s annual budget on sugar “subsidy” to restore 7,000 jobs is sound public policy. Bauxite at Linden and Kwakwani is subsidized annually for $(G) 2.9 billion. Bauxite, like sugar, is a strategic industry around which vibrant communities were built. “If you destroy sugar or bauxite, you destroy those communities, too.”

It is normal public policy for countries to subsidize agriculture, including sugar. For instance, the European Union and the USA subsidize agriculture in the sum of €59 billion and $(US) 22 billion respectively, but the specific size of their subsidy for sugar is not available. In India, the annual subsidy on sugar is $(US) 1.7 billion. These countries rightfully view subsidy as investment.

Why the racist rants? How does Guyanese interpret racism? Simply stated, “racism” is the expression and/or the practice of hate, discrimination, race baiting, and bias directed by an individual or group or an institution against another on the basis of essentially on how they “look or sound.” It is not based upon any classical ideology of innate differences (whether biological or otherwise) but on how one “looks and sound” and which may be buttressed by one’s cultural traits. The latter is captured in the process of “ethnicization.” “Ethnicity” and “race” can be treated as equivalent because of the unique origins of the “six peoples” and both are viewed as drivers of ethnic conflict. It is noted that while Guyanese politicians have the capacity to stir up racism, they did not invent it. But they have been using it as an effective political tool to mobilize their supporters.

The sugar industry shows how the allocation of resources, is often defined by opposition forces as “racism,” or “ethnicization,” rather than by genuine economic need. Linking the allocation of resources with allegations of racism found its fullest manifestation in the early 1960s (1962-1964). This was the period when race insecurity was pronounced and when Afro-Guyanese felt that they would be dominated by the superior numeric strength of Indo-Guyanese, although they (Afro-Guyanese) had full control of the armed forces. However, demographic changes since 2002 have neutralized the effect of ethnicity or race on forming the government which has been the source of the accusations of racism on the premise that governments decide who gets what, why and how.

Given that no race group now constitutes a majority, the level of race insecurity among Afro-Guyanese should theoretically decline since no one group has a demographic advantage. Ironically, Indo-Guyanese continues to feel insecure because of their gross under-representation in the armed forces, although the party to which they are aligned is in power.

There is no evidence in Guyana to suggest that enhanced economic condition is compatible with a decrease in the level of racism. The PPPC says that under its governance the economic position of Afro-Guyanese has been enhanced, but this position did not ease racism nor lead to any significant increase in PPPC support among Afro-Guyanese. During the period 1976 to 1985 the PNC government owned and controlled 80% of the economy, yet that did not translate into any major economic benefit to the Afro-Guyanese people, whose poverty rate exceeded 50% as did Indo-Guyanese. The Amerindian poverty rate was 75%.

Irrespective of philosophical differences, there is some convergence on the notion of “inclusive governance” as a mechanism to minimize racism. However, people’s perception of inclusivity differs; cultural adherents (like Ravi Dev and Eusi Kwayana), for example, believe that inclusivity is best expressed in a federal system, while political and intellectual adherents (like Dr. David Hinds and Vincent Alexander) believe that it lies in executive power sharing. What system is more effective and acceptable will have to be determined by the Guyanese people after a national conversation and the conduct of a referendum.

Pending a resolution on the idea of inclusive governance, some suggested short-term measures to reduce racism include but is not limited to the enactment of equal opportunity laws, compliance mechanisms, affirmative action, quotas, and poverty reduction. Long term measure to ease racism resides in the socialization process where values and habits are internalized and imbedded into children and young adults. It is much easier to learn something than to unlearn it. The socialization process should be a team effort involving parents, schools, churches, leaders, and role models. We start from the home and move interactively to the school, to the church, to the community and then to the wider society.