On July 9, 1999, University of the West Indies lecturer Tyrone Ferguson launched his book To Survive Sensibly or to Court Heroic Death: The Political and Economic Management of Guyana 1965-1985, which examined Forbes Burnham’s political tenure in office. Dr. Ferguson, having grown up during the Burnham years, told Stabroek News that he was motivated by “deep concern at the myths which had been thrown up by the mantra of the 28 wasted years”. He revealed that when he posed the question to Burnham about the CIA putting him in office, Burnham retorted “Tommyrot and absolute Balderdash! The CIA and ourselves, never had any connection”. However, released information from the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) offers remarkable insights into the depth and scope of the interaction between Burnham and the US, revealing Burnham’s calculating and perfidious plans to construct Guyana’s dictatorship amidst growing American geopolitical concerns in the region.

At the height of the Cold War, a “303 Committee”, which included inter-agency cooperation among the US State Department, National Security Council and Central Intelligence Agency, was established to oversee US covert operations in Latin America under the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon Administrations. Between 1962 and 1968, the 303 Committee approved US$2.08 million for its covert operations programme in Guyana. In hindsight, Burnham’s plan to rig the 1968 elections, the first in a series of rigged elections, was part of a grandiose plan to build his dictatorship. Despite the PPP split in 1955, the parting of ways of Burnham and Jagan and ethnic re-alignment, Burnham still had to contend with a growing Indian population loyal to Jagan and a PPP enamored with a superior propaganda, electoral and mobilization machinery – one guaranteed to win a plurality of votes in a free and fair election.

The 1961 and 1964 elections established the pre-conditions, as well as the pretext necessary for Burnham to put his nefarious plan into action. Following the August 1961 elections, the Americans were still prepared to hitch their wagon with Jagan, but they were optimistically cautious, given the unfolding events in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a central character in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, had grave reservations about Jagan’s intentions, and he played a decisive role in shaping US foreign policy towards British Guiana. A more sympathetic Arthur Schlesinger, Kennedy’s Special Assistant, in his memo to Kennedy on August 30, 1961 attempted to “salvage Jagan” by offering Jagan technical and economic support, assistance with Guyana’s admittance into the OAS and Alliance for Progress, and “a friendly eception” with Kennedy during his October meeting. However, after assessing Jagan’s plans for the economic and political development of a future Guyana on October 25, 1961 following his meeting with President Kennedy, the US-Jagan relationship quickly deteriorated. In February 1962, a determined Dean Rusk wrote to his British counterpart advising him that “it is not possible for us to put up with an independent British Guiana under Jagan”. On June 22, 1962, during cross-examination by the Commonwealth Commission of Inquiry into the January riots, Jagan bared his communist credentials for the world to see. By July 1962, the CIA was planning a covert operation to remove Jagan from office. During the first quarter of 1963, the US State Department, American Consulate General and Her Majesty’s Government had agreed on a new electoral system of “proportional representation” to prevent Jagan’s re-election. Not surprisingly, on February 6, 1964, Rusk reminded President Johnson that the “Emergence of another Communist state in this hemisphere cannot be accepted; there is grave risk of Jagan establishing a Castrotype regime should he attain independence”. The stage was set. Jagan’s political folly would lead him into political wilderness for the next 26 years following independence.

The coalition of convenience formed after the 1964 elections was constructed on precarious grounds. Burnham made little attempt to solicit ideas from Peter D’Aguiar and cabinet meetings were held without the UF leader, who held the Finance Minister portfolio. The two men were separated by ideological, personality and temperamental differences, with undercurrents of racial prejudices. D’Aguiar was suspicious that Burnham was trying to coopt the UF ministers. He finally resigned in September 1967 but Burnham’s “uncomfortable alliance” was unbroken as the UF ministers remained in the cabinet, and another replaced D’Aguiar. Burnham kept his eyes on the prize. He had a master plan: jettison the coalition, become the ultimate power broker of an independent Guyana and downplay political ties with the US to boost his nationalist credentials.

Several conditions convinced American policymakers that US support for Burnham was the right approach. One, Delmar R. Carlson, the US Ambassador, the chief negotiator between the US and Burnham, was “gratified” at the outcome of the 1964 election and Burnham’s willingness to work with the coalition. Two, Burnham assured the Ambassador that he was willing to explore ways to include prominent Indians (Balram Singh Rai and Fenton Ramsahoye were suggested) into his cabinet. Third, Burnham agreed with the US stipulation that the government should not include a PNC/PPP coalition, Jagan “or his henchmen”. The US, through Carlson, planned to “counsel Burnham towards moderation and assist him where possible”. A major breakthrough for the US came in February 25, 1965, when the Colonial Secretary agreed to a constitutional amendment permitting Burnham to appoint Shridath Ramphal as the Attorney General.

Burnham received lucrative American aid after the 1964 elections. He was assured of a 25-year contract with Reynolds, the US bauxite company. The company planned to double bauxite production annually by 600,000 tons and he was promised an advance in income tax of US$500,000. Burnham must have been elated when on March 17, 1967, the 303 Committee Memorandum concluded that “it is established US Government policy that Cheddi Jagan, established East Indian Marxist leader of the pro-communist People’s Progressive Party (PPP) in Guyana will not be permitted to take over the government of an independent Guyana”. The challenge for Burnham was to set up a rigging machinery that would place him at the helm of political power and provide architectural design to his political dictatorship, while projecting the fig leaf of democracy. Burnham, however, as the Americans recognized, would first have to build an organization that would include credible Indians and be able to put up a decent challenge to Jagan’s PPP. With the British out of the political equation, Burnham developed a plan for American support that would guarantee his ultimate maximum leadership. The elephant in the room, of course, was Cheddi Jagan, who, as the quintessential Marxist, would pledge his loyalty to the former Soviet Union and support every anti-imperialist revolutionary movement around the world.

The crucial 1968 election in post-independence Guyana demanded Burnham’s compelling attention. US support for Burnham came in 3 forms: 1) Ensure the survival of Burnham’s government, 2) Provide economic assistance, and, 3) Provide direct funds to create an elaborate electoral rigging machinery.

A November 20 memorandum, following the 1965 London Constitutional Conference, highlighted Burnham’s plans for West Indian migration and his idea that “under the new constitution absentee voting would be permissible”. During a meeting with President Johnson at the White House on July 22, 1966, Burnham had revealed that his electoral chances for winning the 1968 elections would significantly increase if Africans migrated to Guyana. If his West Indian African migration scheme could accommodate 15,000 – 20,000 immigrants, he would solve his electoral problem. A memorandum from the Deputy Director for Operations of the CIA (Helms) to the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs on December 10, 1965 shed light into Burnham’s “immediate objective” which was meant to “launch his economic development plan so that he will be able to induce large numbers of West Indians of African descent to settle in Guyana prior to the December 1968 elections”. However, the immigration scheme was abandoned because there was insufficient time to implement it, some of Burnham’s supporters opposed the plan and a 15% unemployment rate did not create a welcoming environment for potential migrants from regional states. This was not the end of it. According to the US Consulate General, Burnham also considered unitary statehood with Barbados, Antigua, Grenada and St Kitts, as well as the “disenfranchisement of “illiterate” voters”.

With the abandonment of the West Indian immigration scheme, Burnham concocted another plan to hyper-inflate his electoral support. A telegram from the US Ambassador in Guyana to the State Department on July 15, 1966, noted that “Burnham had confessed to colleagues that he intends to remain in power indefinitely – if at all possible by constitutional means. However, if necessary, he is prepared to employ unorthodox methods to achieve his aims”. In a meeting with US officials on September 16, 1966, Burnham informed the Americans that he would need financial support for “staff and campaign expenses, motor vehicles, small boats, printing equipment, and transistorized public address systems” and a contract “for the services of an American public relations firm to address his image abroad”. On April 10, 1967, the 303 Committee approved financial support for Burnham, but the exact amount was redacted from the documents. A December 6, 1967 memorandum from the Deputy Director for Coordination of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (Trueheart) to the Director (Hughes) and Deputy Director (Denney), made a startling revelation: Burnham would be paid in twelve monthly installments “to help him in revitalizing his party and in organizing his absentee vote strength…these measures, it was hoped,, would forestall the necessity of exile of Jagan, or his detention, or coup d’état after the election”. In other words, Jagan would be prevented from taking office – by any means necessary. The 303 Committee wrote in a memorandum (May 23, 1969) that the CIA should “provide $10,000 a month for two years to support his efforts to build his party…into an effectively, permanently organized political party”. Ambassador Carlson recommended a $5,000 monthly subsidy paid to Burnham for the next two years.

Carlson revealed that in June 1967, Prime Minister Burnham said that “overseas vote figures could be manipulated pretty much as he wished”. In a prior meeting with Carlson on September 16, 1966, Burnham “outlined his plans to issue identification cards to all Guyanese above the age of 10, and to identify and register all Guyanese of African ancestry in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States in order to get their absentee votes in the next election”. In the same meeting, “Burnham acknowledged with a smile, East Indians living abroad may have trouble getting registered and, if registered, getting ballots”. To implement the registration process, a portion of the funding approved by the 303 Committee was used to publicize Guyana’s progress to attract overseas voters. Burnham originally intended to secure 50,000 overseas Guyanese registered to vote. The problem was that there were not so many Guyanese abroad so that his government ended up creating “jumbies” and even registered horses to vote. In the end, by January 1968, registration of Guyanese over 15 at home was completed. A whopping 68,588 individuals from 55 countries were registered to vote in the 1968 Guyana elections.

Of the 312,391 votes cast in the 1968 elections, the PNC “obtained” 55.81% and the PPP 36.49%, presumably with 85.1% voter turnout. The fudged mathematics continued to work in Burnham’s favour: the PNC “won” 70% of the votes in 1973 elections, 77% in 1980 and 78% in 1985. These results suggested that a large number of Indians who supported Jagan’s PPP in 1964, had since migrated to the PNC’s camp, a questionable reality debunked by international organizations which documented the massive fraud associated with these elections.

Burnham is often praised for his oratorical skills and charismatic appeal among Africans, but he is better known for his Machiavellian manoeuvres. The Americans miscalculated, not knowing that Burnham would work to adopt nationalistic and progressive foreign policy positions in a desperate attempt to shed his image of an American puppet. In the process, Burnham transformed Guyana into a dictatorship. With Jagan still in the political wilderness, and except for a brief challenge from Walter Rodney, who had declared that Burnham must go “by any means necessary”, Burnham’s dictatorship would last until 1992, seven years after his untimely death. Ironically, it was the Americans, including former President Jimmy Carter, who would contribute towards a dismantling of the Burnham dictatorship.

Dr. Ramesh Gampat, in a forthcoming book (2022) from which some of the materials here have been extracted, has written that Burnham’s unholy alliance was a “prelude to dictatorship, economic devastation, the entrenchment of corruption, pillage by multinational corporation, political tribalism, rise of a class kleptocrats and plutocrats, crime, violence and destruction of property, marginalization and discrimination. It is primarily Indians who have been at the receiving end. In effect, the US, with the tacit approval of Britain, created the conditions for what have kept Guyana on the verge of a failed state from the 1960s to the present.” While the legacy of Forbes Burnham looms large, it is perhaps his sister, Jessie Burnham, who offered the unkindest cut of all: “Behind that jest, that charm, that easy oratory is a certain dark strain of cruelty which surfaces when one of his vital interests is threatened. These are the two Burnhams; the charming and the cruel. I say BEWARE of both.”

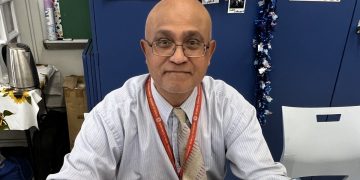

Dr Ramharack teaches politics and history at Nassau Community College (New York). He is currently working on a forthcoming publication on Alice Bhagwandai Singh, a Guyanese activist who played a defining role in negotiating a cultural space for Indians during the pre-World War II era.

By Dr. Baytoram Ramharack