It is not known how many Guyanese migrated abroad and how many children, grand-children, and great-grand of theirs are born overseas. In short, the size of the Guyanese diaspora, those who maintain trans linkage with the homeland, is not known. But the number exceeds 1.5 million plus the descendants born abroad of Guyanese migrants, adding a couple hundred thousands. This number is twice the current population of the country of an estimated 750K. Over one million, including children born to Guyanese parents and their other descendants born abroad, are settled in USA alone; some 350,000 live in Canada plus children and other descendants of Guyanese, and another 60,000 plus children and other descendants of Guyanese in UK. Guyanese are also scattered all over Western Europe and in Australia and throughout the Caribbean, Venezuela, Suriname, Brazil, and French Guiana. It is estimated that over 60% of Guyanese migrants and children born abroad are Indian Guyanese based on ethnic trends of those who migrated from the former homeland. The Indian population in Guyana declined from 55% in 1980 to 40% in 2020, suggesting large scale migration. In fact, over ten thousand Indian Guyanese emigrated annually from the 1980s onwards and thousands annually in preceding years.

Why and how did Guyanese migrate to USA and other countries? Historically, it has been a major challenge for most people in Guyana to find gainful employment after slavery (ended 1838) and indentureship (began in 1834 with Portuguese with Indians in 1838 and Chinese in 1853; Portuguese indentureship ended in 1882 and Chinese in 1879 while Indian indentureship ended in 1921). Initially every worked on the farms or plantations. After indentureship, Africans, Chinese, Portuguese moved away from toiling on plantations and pursued other means of income while Indians remained on the plantations. During the late 1800s and later, Africans were drawn to state employment while Mixed races, Chinese, and Portuguese were drawn to business; some Mixed and Portuguese also worked for the state and continue till this day. Most of the Portuguese and Chinese migrated by the end of the 1970s. Indians were initially on the farms after indentureship in 1921 and later some went in the private sector as entrepreneurs and clerical staff. As they accrued savings, some Indian families began sending their children during the 1930s and later years to pursue professional studies in medicine, law, and engineering in UK and India; a handful (like Dr. Cheddi Jagan, Ptolemey Reid, among others) went to USA to study before WWII and also returned home. Upon return, they joined the professions working for the state and or opened private practices. After the race riots in the early 1960s and the colony obtained independence in May 1966 amidst a sense of ethnic insecurity, professionals began migrating. Discriminatory policies post-independence especially against Indians and the rise of the authoritarian state triggered a wave of migration.

A general limitation of job opportunities caused many Guyanese, Indians in particular, to migrate to other countries to pursue tertiary education and or to seek gainful employment beginning in the 1950s and increasing during the 1960s and subsequent decades. Initially, they emigrated to the UK while the territory was still a colony (up till 1966) of Britain when it was easy to gain admission into the metropolitan imperial nation. Some also ventured into the US as visitors and or students during the mid-1960s with the intention of pursuing employment. When the colony obtained its independence in 1966, emigration to the UK began to experience restrictions on Guyanese migrants but they continued to arrive in England as students and or visitors, pursued employment, and settled down. As Guyana became independent in 1966 leading to tight border control in England, the USA in 1965 opened up its borders to migration from non-traditional non-White countries like Guyana. Guyanese took advantage of the new immigration rules and began emigrating to USA after 1965. Guyanese began arriving in New York as visitors, students at tertiary institutions (mostly trade schools), and as professionals to work in skilled jobs. Those with technical, medical, scientific, teacher training, and accounting (bookkeeping) skills were able to regularize their status with residency sponsored by employers. Meanwhile, Guyanese who were in UK, through various means regularized their status and settled down making the UK their new adapted home. Migration to UK continued but not with same intensity as during the 1950s and 1960s. Less and less Guyanese chose UK to migrate during the 1970s and later years; students seeking university degree studies opted for UK. But America became the star attraction with thousands migrating annually during the 1970s and over ten thousand yearly in the 1980s and subsequent years. Guyanese immigration to Canada also began during the 1970s as students and visitors with almost all of them pursuing employment in violation of their visas. They were able to regularize their status with residency and citizenship through employment and or self-sponsorship (because of education and or skills and investment).

Early emigration of Guyanese (from the 1950s thru the 1980s) was primarily among those individuals or families who had savings to afford the trip of a kin. Some ‘bought’ visas to gain admission into USA and Canada during the 1970s and 1980s. Some were also able to buy visas to USA and Canada during the 1990s. Many Guyanese paid huge fees to obtain documents, some involving impersonating as others (like Americans or Canadians) and made successful entry into USA and Canada; they were able to regularize their status. The process of making an entry through the non-regular way came to be known as “back track’. Thousands of Guyanese exited the country and made their way to USA and Canada through the back track process. The fee for ‘back track’ or even to purchase a visa was very high, out of reach of ordinary Guyanese. Almost everyone who purchased visas or traveled ‘back track’ were Indians. It required enormous sacrifices of savings to afford the trip. And reaching North America or even a Caribbean Island was not always guaranteed; many were deported back to the homeland with some even spending time in jail in in transit islands in the Caribbean with defected or forged passports and documents or impersonating others using their documents.

Income was always very low in Guyana to afford a trip to North America or UK for a vacation or to pursue studies. During the 1950, with an annual income of less than US$300 and the 1960s with an annual per capita income of less than US $350, few Guyanese ventured to travel abroad that costed thousands of dollars. The per capita income of the 1970s was less than $400 and during the 1980s had not improved much when factoring in rising inflation. But families were able to acquire funds through savings and or borrowing to send a kinship member to North America or UK. Teachers and other professionals had much higher income than the general per capita and accrued savings to afford to travel abroad and or pursued higher education. With accrued savings, joint contributions of family members, and or through borrowing, more and more Guyanese were able to fund the trip to UK, USA, Canada, and Caribbean islands; the latter territories, Venezuela, Brazil, and French Guiana become a destination during the mid-1980s onwards as US, Canada, UK tightened entry requirements of immigrants. Tens of thousands of Guyanese settled in the Caribbean islands. As the economy was tanking, tens of thousands of Guyanese settled in neighboring Venezuela during the 1980s and 1990s. And thousands also settled in Brazil, tens of thousands in Suriname, and thousands in French Guiana, making their way there through Suriname into the French territory to pursue employment opportunities.

As they settled down in the new adopted land in UK, USA, and Canada during the 1950s and later years and found gainful employment and were able to accrue savings, they began sending remittances to assist family members at home. They encouraged others to join them. Some financed the trip of kins to join them. As remittances were received, standard of living improved for kins in Guyana. Seeing the economic progress made by others, more and more individuals and or families at home began making major sacrifices, putting off gratification, and saving as much money as possible to invest in family member (s) going abroad. In time, those living abroad since the 1950s and subsequent years were able to regularize their status (residency and citizenship). They sponsored family members to join them. Guyanese began arriving in USA by the thousands annually during the 1970s and by the 1980s the numbers had climbed to over 10,000 yearly and in subsequent decades. The majority of Guyanese who emigrated were Indians, estimated at over 60%. By the end of the 1970s, almost all Chinese and Portuguese had migrated to USA, Canda, UK, and Caribbean islands where they established businesses. Many Mixed Guyanese who historically had enjoyed special privileges in Guyana because of their color (approximating closeness to Whites) also migrated, opting for Caribbean islands. Africans migrated to North America and UK and those who could not make it there chose the Caribbean islands. Indians had preferred North America and UK but chose the Caribbean Islands, Suriname, and French Guiana when not possible to make it to the developed countries. Amerindians migrated to neighboring countries of Venezuela and Brazil. Almost all Guyanese migrants from all parts of the globe sent remittances or material handouts (came to be known as the ‘barrel economy’ including food and clothing to kins and friends back in Guyana to mitigate the hardship and drudgery of life in their former homeland. Everyone wanted to help their loved ones and friends and their communities. But almost all remittances and handouts came from the rich developed countries with USA (Guyanese-Americans, residents and citizens as well as undocumented) sending the bulk of cash and materials.

The migrant communities in UK, USA, and Canada contributed to the socio-economic development of both the new host societies as well as the home countries left behind as well as their own lives in their new adopted homeland. Initially migrants were scattered residing anywhere that had low-cost rent. Groups of them lived in rooms or apartments and nearby to each other. It was not long before they started to cluster. As the migrants settled in clusters, communities were organized and developed organically. The migrants began transplanting their way of life in the host countries, building institutions (places of worship, shopping of ethnic goods and clothing, restaurants, offices, etc.). As communities were established, there began to emerge engagement of the migrants (diaspora) with the country left behind – their villages or neighborhoods, government, schools, organizations, religious institutions, businesses, etc.

In time, there began transfers of human and capital resources (money and technical skills) as well as investment in the former homeland. Remittances and diaspora investment as well as investments helped to improve livelihood back home and contributed to economic growth. Remittances made it possible to combat poverty and to refurbish houses or build new homes and to re-habilitate entire neighborhoods in the country of origin. During crises, like flooding, man-made disasters like infernos, or Covid 19, the diaspora galvanized into action and sent support to mitigate fallout. And when there was rigging of elections and the attempted rigging of the 2020 election, Guyanese, primarily Indians, lobbied western governments for intervention to restore democratic traditions.

In addition to helping to their former homeland economically, Guyanese contributed to the development and growth of their host countries. The migrants paid large amounts of taxes as employees and consumers. Some also started businesses and or purchased homes or multiple buildings paying huge real estate and corporate taxes. Their taxes helped to fuel the national economy as well as the state and local areas where they reside. Many businesses were opened to serve the growing Guyanese community as well as others. They pursue entrepreneurial initiatives within and outside their communities. Their investment, businesses, and expenditures created jobs for other Guyanese and members of other groups.

Guyanese business, including medical and legal offices, clubs and restaurants, catering halls, NGOs, religious establishments, among others provide various services for the diaspora including administrative services, social and intercultural entertainment, educational and cultural activities, support in immigration status change, etc.

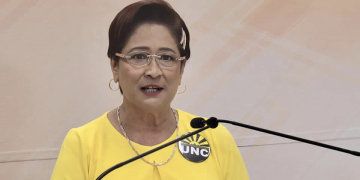

Besides sending remittances and handouts (barrel and container economy), they are in a position to assist their former country with other forms of assistance like lobbying the government of their adapted homeland for policies beneficial to their former country. However, Guyana does not a very active or action-oriented diaspora policy. There is a core policy on paper on the diaspora but not effectively pursued or implemented. It is not even clear if the government has data on the diaspora and understands its capacity of aiding in Guyana’s development. The diaspora was pursued for assistance when there was a crisis or emergency or for funding for elections in the former homeland. Millions of dollars were raised abroad for every election going back to 1992 (1997, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2015, 2020). Indian Guyanese diaspora gave generously to the PPP, they party of Indians or the party with which the Indians have been aligned since 1955. Africans and Mixed gave to the PNC, the party to which the Africans and Mixed have been aligned since the 1955 split in the original multi-ethnic PPP founded in 1950. For the 2011 and 2015 elections, Indian Guyanese diaspora also gave generously to the AFC and PNC (APNU), helping to bring about the defeat of the PPP in 2015; the PPP also lost its majority in 2011 when AFC captured seats from it on the Corentyne and in Essequibo, areas known to be the Indian and PPP heartland.

Currently, the government has core policies on the diaspora and occasionally government officials interacted with the diaspora when they pass through the metropolitan cities or even the islands of the Caribbean. At times, succeeding governments sent officials to meet with diasporas in the metropolitan countries but hardly any concrete achievements came out of the visits. Every government encouraged Guyanese to re-migrate to or invest in their former homeland. But when they returned home, they complained they have not been embraced and were given the run around to achieve desired objectives. They complain bitterly of experiencing hiccups in obtaining licenses or clearances for investments; they are required to give ‘a raise’ (bribery or ‘backshish’) in order to process paper works. Laws against graft and corruption have never been enforced. Only when they met the President or Vice President or some other top officials were blockages cleared and they were able to achieve desired goals.

There are investment guides for diaspora that is available on national platforms, and there were several high-level exhibitions for entrepreneurs to showcase their products and services or to encourage investments. No government going back the 1970s have been very successful at leveraging the diaspora for national development efforts. Guyanese in the diaspora complain that they have not been genuinely engaged for sustainable development. Also, experts or specialists on the diaspora have not been engaged or consulted on leveraging the enormous resources of the diaspora – talent, skills, capital or financial, administrative, logistical, capacity-building, etc. The Guyanese diaspora in America alone has hundreds of billions of dollars in savings that can be invested in Guyana or offered as loans for development projects instead of Guyana borrowing money at exorbitant rates. By drawing on the resources and other diverse potential contributions of the Guyanese diaspora, much more can be accomplished to achieve rapid development. More needs to be done by government to reach out and engage diaspora to strengthen ties and encourage investment. Government should consult with those who know and understand the diaspora and the potential role they can play in aiding their former homeland. Government must deepen ties with the country’s diaspora in the emerging new petro economy.