Foods of the indentured laborers (girmityas) were similar to the peasants of India. The indentureds came between 1838 and 1917. The food habits in India were transplanted in the new society where they indentured lived and have been continued by the descendants.

During the 1800s and much into the 1900s, the peasant Indian foods were universal comprising a basic, skeletal or spartan diet of a few items. Food habits changed as a result of the agricultural revolution; people also had more to eat in the later 1900s than in the 1800s or first half of the 1900s.

Seven curries as “is” (group of dishes) known today, a term for foods served in Guyana after a Hindu religious function, were not a part of the diet of or that was served by Hindus and that did not become popular in Guyana until the 1990s, some seven decades after indentureship was abolished on January 1, 1920.

It is not clear how the term seven curry emerged in Guyana and is used only in Guyana, not in the rest of the diaspora. It was not in vogue up until the 1990s. And it is still not used in certain parts of the country among Hindus. The term generally used for a Hindu religious event for the meal served is bhoj or bhojan. Even in USa or Canada or UK, seven curries is not used. It is bhojan. India, it is maha bhoj. It is served after a puja or Hindu wedding. The scriptures mention certain food items. And it does not have to be seven curries. Most Hindu functions have many more dishes and some may have less. Pujas I attended in urban India had more than seven curries and in the rural villages some had only four or five. I sponsored bhojs in India with only four or five items.

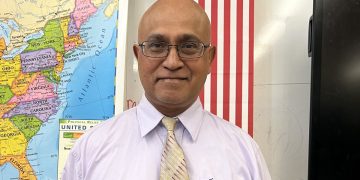

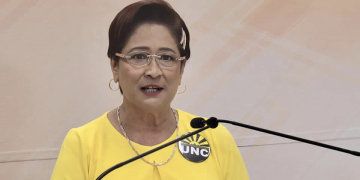

President Irfaan Ali made brief comments on social media about the popular seven curries and how they were initially prepared by the indentured or how the foods came about. The President’s comment was sent to me for a response or clarification. I was in India at the time attending the PBD 2025. I spoke at a seminar at a university on Indians in the Caribbean – an Anthropological presentation. There were questions on Indian cuisine in Guyana. I learned a lot about food in the villages of India and that would have been consumed by the peasants and the indentured before they left for the Caribbean or elsewhere as well as when they were on the plantations. The foods are similar although in India, foods are richer in spices that are difficult to tolerate by Indo-Caribbeans.

The President misspoke unintentionally. The President made some fundamental errors in food preparation by the indentured or the peasants of India; contrary to what he stated, very few foods were steamed. And only a few items were roasted as when making chowkah and sada or skaey roti. The indentured received rations from the planters that included tale or oil, rice, flour, dhal, onion, garlic, among, other items. They grew some commonly used kitchen items for seasoning and for access to vegetables. The indentured had to budget themselves how much food was to be prepared or consumed and the oil and other items used. They had to purchase items not available from the ration or if used out before the next month’s rations. All vegetables were prepared using oil or tale. Only certain foods were cooked with a ghee base. And no tasty or delicious vegetables were cooked without oil, meaning only steamed as the President suggested.

The foods consumed in the villages were not of seven vegetables although it was served among the richer farmers. People ate what they grew and some grew a variety of vegetables on their small plots of land. This writer visited several villages and observed farming (tilling and cultivation) as well as harvesting. Crops were rotated. Transportation was primitive in the villages during the 1800s and earlier. So people depended on the foods grown in the area – rice, wheat, oil and several vegetables including onions which was like a staple. Meat was not available and forbidden by scriptures. And at any rate, it was unaffordable for the masses.

There were not many varieties of food during the 1800s. Trade was not very common because of primitive means of transportation. The introduction of railways by the British led to cultural diffusion – in which there was access to greater varieties of vegetables all year round especially during the 1900s. And as President Irfaan Ali rightly stated, ghee was not commonly used as a staple because of affordability. But certain foods needed ghee for preparation – mohanbhog and kheer. Sarso or mustard oil and coconut oil was used for cooking. Ghee was needed for religious rituals and put in a few foods as a luxury item to add to taste.

The food or cooking habits has not changed much from the 1800s to today among the poorer class of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (some also came from Madya Pradesh, Bengal, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu) from where the indentureds to Guyana came – the Bhojpuri and Hindi belt. Off course, people have become health conscious over the last couple decades. And there are greater varieties of food today as a result of modern transport. During the 1800s, food was cooked from chulha or fireside using cow dung; wood was expensive while cow dung was nurtured. The indentureds also used cow dung and wood. More people use gas today subsidized by the Indian government. In Guyana, food was cooked with chulha and wood fire; most Guyanese use gas stoves instead of chulha. When kerosene was scarce during the 1970s and 1980s, many Indian Guyanese turned to cow dung and busey and wind paddy as a fuel.

The indentureds (from the north — Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) or those shipped out of Kolkata (Calcutta) had slightly different food habits or cuisine than the indentureds from the south (Madras, now Chennai). But dhal, rice, roti or puri (variety of rotis), and subzi (sabjhi) or vegetables were standard and common for all. Dhal, rice, and roti were staples. The indentureds were almost all peasants or rural dwellers and very poor. The base of cooking was oil or tale and ghee. Some foods were steamed or cooked without any oil or ghee (like certain roti) and chowkah. Ghee was very costly. Few items had ghee which was also required for pujas among Hindus. Oil or ghee was added to chowkah. The base or feature of meal preparation (oil and or ghee) depended on the season and what was available and one’s affordability. Virtually no curry or vegetable was cooked without oil or ghee. In the north, sarso or mustard oil was used; in the south, coconut was common.

India has two main seasons and different foods are grown in each and in different areas. In the winter, in the north (November thru March), there was or is wheat and various dhals. Rice is grown all year round in south and warm rainy season in the north. The indentureds used yellow dhal or arahar that is grown north. There were various other dhals in the north including moong, urad, masoor, among others. They fetched different prices in today’s markets.

The peasants ate mostly what they grew and what was immediately available in their neighborhood. They purchased and or exchanged crops for home use. The home grown vegetables or subzi (sabji) were baigan or brinjal or egg plant (various kinds), cauliflower pool (flower) cabbage (winter), green or yellow cabbage (all year), parwol, various bhajjie (mustard poi, etc.), matar or green peas (winter), bindi or ochro, lauki or squash, karela, pumpkin or khora, sag or chaurai bhajjie, palak or poi and the green leafy vegetables, chilli or hot pepper, saijan, carrots or gajjar, sweet potatoes or kand (all year), Channa, alou or English potatoes (winter) sag or green leaves of young vegetable plants, channa, radish or mooli, nenwah, jingi, banana, or mango pickles, lemon pickles, katahal or jack fruit or katahar, bora or bodi or long beans, onions, garlic, among others.

Ultimately, the type of food (vegetables cooked) depended on affordability even among the poor peasants. Bananas were not readily grown in north; it was a south dish that is now common in the north and also cooked in Guyana. Tomatoes came much later as a traded food item; now it is widely grown in north in the non-winter months. Kitchri was and still is very popular all over the country including in Guyana. Satoo or satwa (seven grounded uncooked grains) was popular; a dried dish on which is added water or milk. Some may add sugar or spices; it is quite reluctant nutritious is it is all protein. Sugar cane was used to make jaggery or gud (gudara) that is used to make sweets or mitai. Rice and corn were used to make lawah or bhuj that was very popular (dried snacks) which was often mixed with masala, onion, etc. or even sugar. Nuts were also grown among the peasants.

Every peasant had cattle (cows, buffalo, goat, etc.) that was used to tend the field. Milk was traded or exchanged. If one had a few cattle, one was prosperous. From the cattle, the peasants got milk which was sued to make paneer, dahi, ghee, sweet rice or kheer. The indentured tended to buffaloes and steers in the fields. Some purchased cows. The milk was used to make Desir or local ghee at home. Home ghee is very tasty, quite different from commercially sold ghee. Many made coconut oil which was used to prepare vegetables. Certain foods needed ghee like mohanbhog or milk like kheer. Puja needed ghee as do varied rituals involving birth, janao or christening, marriage, and death.

Although there are greater varieties of foods today, the staples remain the same in the rural villages of the Bhojpuri belt and in Tamil Nadu and even in Madya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan, etc. – rice, dhal, roti, and vegetables. Food is still cooked with oil (now there is a variety like mustard, corn, sunflower, etc.) and greater use of ghee. Most Hindus still refrain from meat, and beef is still prohibited in most parts of the country even among Muslims. And health conscious people have reduced ghee consumption especially when heated or cooked. Now, there are a varieties of parathas instead of a few types of roti like sakay, dosti, dhal puri, fried puri, and paratha (all types with fillings).

Ghee was not commonly used because of affordability. Ghee was not recommended as a staple. Desi ghee was poured in or in some items for flavor. Fried puri was very popular. It was a delicacy. Small quantity of oil was used to make a subzi (sabhji) or vegetable. Puri was cooked in oil, at times mixed with ghee. Dhal and roti was popular as an evening meal and remains so till this day. Dhal is a major source of protein – an energy source. All types of vegetable chowkah are consumed with baigan the most popular that goes with dhal and bhat (rice) and roti.

In the Bhojpuri belt, Litti or thick roti was made – comprising different grounded grains and millets, wheat, corn, and various dhals. This roti could last for days without spoiling. The peasants had animals that were used to plow the land. Depending on the household animals, milk was obtained and various products made. There was home or Desi ghee that was also made in Guyana by cow herders thru the 1990s; many Guyanese farmers still make home ghee. Milk was also used to make dahi, chaach or butter milk (filtered dahi) called mattha. Ladoo as a sweet was also popular at puja and at weddings.

Kitchri (rice cooked with dhal, grains and various seasonings) was also popular with the indentured and is so till this day among the descendants and all over India.

In terms of fruits, the most popular ones were: guava or amrut, different kinds of melon (water, bus, foont or long), mangoes, lemon, bananas, ganna or sugar canes. The cane juice was boiled to make jaggery or gud (pronounced gudara). Various sweets were also made sweets from juice. Vinegar was made from from sugar cane juice and used in meal preparation or to make pickles. The most popular pickles were mango or amchar and lime and lemon. The delectable food habits of the rural peasants that were transplanted by the indentured in Guyana and indeed through the diaspora are now enjoyed by other ethnic groups.