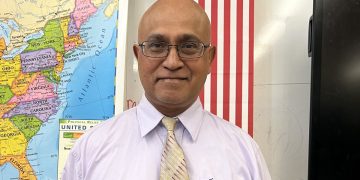

Author: Rachna Chandela

Forensic Scientist (Toxicology) Guyana Forensic Science Laboratory,

Guyana, South America

Abstract

The development of forensic science is commonly associated with modern scientific advancements; however, its conceptual foundations can be traced to ancient civilizations. This paper examines selected narratives from classical Indian texts—namely the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and Kautilya’s Arthashastra—through the analytical framework of contemporary forensic science. By examining judicial reasoning, evidence evaluation, witness testimony, intelligence gathering, toxicological knowledge, and behavioral analysis embedded within these texts, the study demonstrates that ancient India possessed a structured, rational, and evidence-oriented approach to crime investigation and justice. The findings suggest that these early practices constitute proto-forensic systems that parallel modern forensic methodologies in principle, if not in technology. This interdisciplinary analysis contributes to the global discourse on the historical evolution of forensic science.

Keywords: Ancient Forensic Science, Indian Legal History, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Arthashastra, Evidence Evaluation, Toxicology, Criminal Investigation

Introduction

Forensic science is widely perceived as a product of modern scientific innovation; however, historical evidence suggests that its foundational principles existed long before the advent of contemporary technologies. Ancient Indian civilization developed sophisticated legal and investigative mechanisms grounded in logic, ethics, observation, and empirical reasoning. Classical texts such as the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and Kautilya’s Arthashastra reveal systematic approaches to crime detection, evaluation of testimony, intelligence operations, and toxicological practices.

This chapter aims to critically analyze selected episodes from these texts through the lens of modern forensic science, highlighting conceptual parallels in evidence-based reasoning, behavioral assessment, and judicial procedure.

Forensic Reasoning in the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata is not merely a mythological epic, but a mirror of the social, moral, and judicial consciousness of ancient India. This study analyzes the events of the Mahabharata in the context of modern principles of forensic science and also demonstrates how psychological character analysis, oral evidence, ethical considerations, and reasoned decision-making—all important aspects of forensic science today—were clearly evident in that era.

Draupadi’s Disrobing: Ethical Interrogation and Judicial Analysis

The episode of Draupadi’s disrobing described in the Mahabharata, is viewed in the light of ancient forensic science, it becomes clear that justice at that time was not solely based on punishment or claims, but also on elements such as religion, morality, and social decorum. Although modern forensic techniques such as DNA analysis, fingerprinting, or scientific crime scene investigation were not available at that time, there were specific ancient legal and judicial methods for identifying and evaluating crime and injustice, which we can call “proto-forensic science.” In ancient India, the role of witnesses, the mental state of the perpetrator, and the examination of the behavioral standards prescribed by the Dharmashastras played a key role in the investigation of crime. Draupadi’s eloquence in the assembly and her question—”Can Yudhishthira, who has no control over himself, stake me?”—is a type of ancient forensic examination, which we might today call ethical interrogation or argumentative reasoning. In this context, the assembly can be considered a kind of judicial forum, where all the eyewitnesses, the accused (Yudhishthira, Duryodhana, etc.), and judge-like figures (Bhishma, Drona, etc.) were present. The acceptance of Draupadi’s religious and moral arguments in the judicial process reflects the importance of logic-based justice in the legal system of that time. This was a type of oral testimony, equivalent in value to the evidence presented in courts today. In ancient forensic science, the offender’s body language, silence, or tendencies to shirk social responsibility were also considered as evidence. The silence of Bhishma and other elders during the Draupadi disrobing incident was a significant indicator from the moral perspective of the time—this silence, in some ways, indicated support for or support for the crime, which today can be analyzed through behavioral forensics or non-verbal cues analysis. The use of symbols such as the Agni Pariksha (fire test), the test of truthfulness, oaths, and curses in ancient texts were also contemporary forms of forensic science, used in the process of identifying crime and administering justice. Draupadi’s appeal to Krishna for help, and her protection by the eternity of her shawl, symbolize the spiritual legal system of that period, indicating that the concept of Divine Justice was also prevalent as an influential technique in the adjudication of crime.

Analysis of this incident demonstrates that forensic science in ancient India was based not only on physical evidence but also on multi-layered elements such as testimony, moral reasoning, behavioral cues, socio-cultural norms, and divine intervention. The Draupadi disrobing is an ideal case study, demonstrating that the foundations of forensic thinking in India are very ancient and multi-layered.

Karna’s Identity: Testimonial Evidence and Verification

The episode of Karna’s identification in the Mahabharata highlights the important role of evidence and testimony in ancient India. When Kunti accepted Karna as her son, this event exemplifies verification through oral testimony, equivalent to today’s paternity test. In the modern scientific age, DNA testing is used to confirm paternity, but in ancient India, verification was based on testimony and evidence. Kunti’s testimony was accepted as true, and Sri Krishna confirmed it, symbolizing the verification of the truth and trustworthiness of evidence in the judicial process of that time. This process clearly demonstrates that justice in ancient India was based not only on physical evidence, but also on a person’s testimony, morality, and beliefs.

This incident confirms the ancient legal view that oral evidence was crucial for verifying testimony and evidence. Kunti’s testimony and Sri Krishna’s confirmation demonstrate that moral and mental testimony held as much importance in the ancient Indian judicial system as physical evidence does in today’s forensic science.

The Dice Game: Circumstantial Evidence and Moral Liability

In the Mahabharata narrative, the dice game emerges as an event that, while not a criminal act in the conventional sense, nevertheless became a symbol of profound injustice. This event not only caused humiliation and suffering for the Pandavas but also ultimately laid the foundation for the devastating Kurukshetra War. The Pandavas’ accusations of fraud and dishonesty against Shakuni and Duryodhana underscore the importance of establishing truth in conflict situations.

While war may have been the ultimate means of resolution, it was rooted in a strong desire for justice and the vindication of legitimate claims. One thing becomes clear throughout this entire episode: the ability to discern between justice and injustice rests on the ability to discern truth from falsehood. The arguments presented by both sides were not merely recountings of events but also moral interpretations of actions that influenced the final decision. This shows that even when concrete physical evidence was absent, the need was felt to determine guilt on the basis of oral and circumstantial evidence. Thus, when the process of justice becomes clouded, it becomes imperative to seek the truth and resort to moral conscience.

Krishna: From the Mahabharata’s Divine Guide to a Modern Forensic Approach

In the enigmatic and complex narrative of the Mahabharata, Lord Krishna is not merely a divine guide or spiritual leader, but also emerges as a skilled investigator, mediator, and strategic analyst. His role and style appear strikingly similar to modern forensic and legal investigation procedures.Acting as a diplomatic envoy between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, Krishna not only maintains neutrality and communicates with both sides, but also systematically gathers crucial information, evaluates the veracity of claims, and anticipates the long-term consequences of potential actions. This analytical approach is consistent with the methodical process adopted in forensic investigations today.

Krishna’s in-depth conversations with both sides were not merely dialogues, but a form of detective work—where he listened to narratives, evaluated complaints, and compared conflicting facts and perspectives. This process is similar to how a modern investigator uses various witnesses, the interrogation of suspects, and physical evidence to gain a holistic understanding of an incident.Importantly, Krishna not only examines the superficial layers of events but also identifies the underlying motives—such as Duryodhana’s lust for power or the Pandavas’ pursuit of justice. This deep understanding resonates with modern concepts of psychological profiling and behavioral forensics, which analyze a person’s motives and mental tendencies to draw more accurate conclusions.

Thus, Krishna’s role is not limited to that of a religious or mythological character, but also that of a discerning investigator in search of justice and truth—a role that appears to be deeply connected to the fundamental principles of today’s forensic science and legal systems.

Abhimanyu’s Death and the Search for Truth from a Forensic Perspective

Abhimanyu’s death was a deeply tragic and decisive turning point in the Kurukshetra War, evoking not only grief but also a profound yearning for justice. While the collective identities of the warriors who participated in this much-celebrated event—such as Dronacharya, Karna, Dushasana, and others—are clearly documented in the Mahabharata, their specific roles and the actual circumstances of Abhimanyu’s death demand analysis from a contemporary perspective. A thorough understanding of these aspects relies on the testimony of surviving witnesses and a close examination of battle accounts.The Mahabharata narrative provides a detailed description of the complex formation of the Chakravyuha and Abhimanyu’s lone entry and struggle within it. Although these descriptions are literary, they embody several principles consistent with modern forensic science—such as the importance of eyewitness testimony, reconstructing events, and recognizing individual responsibility in a mass attack.

Abhimanyu’s Death: A Forensic Analysis

The Role of Witnesses – In today’s forensic investigations, the sequence of events is understood with the help of witness statements. Similarly, the surviving warriors and storytellers of the Mahabharata war were able to tell who attacked Abhimanyu, when, from which direction, and with what strategy. Their descriptions would have been helpful in reconstructing the events at that time.

Reconstruction of the Incident – Forensic experts currently study the body, the nature of the wounds, the type of weapons, and the condition of the crime scene to determine the true nature of an incident. In the Mahabharata, the description of Abhimanyu’s fighting style, his speed, defensive strategies, and the direction of the blows provides a vivid glimpse of his final moments.

Analysis of Mass Attacks – Today, with the help of scientific techniques, investigators can analytically identify the role of each individual involved in mass crimes. The description of the roles of Drona, Karna, Ashwatthama, and other warriors in the Mahabharata narrative suggests that even then, it would have been possible to identify the individual involvement of each attacker, if the case were considered with the same scientific perspective as it is today.

Re-evaluation from the Perspective of Justice—Thus, Abhimanyu’s death was not merely a heroic death, but a complex and thought-provoking event from the perspective of judicial and moral analysis. Its chronology—including testimonial accounts, reconstruction of the battle sequence, and study of the roles of the attackers—appears in today’s context to be akin to analyzing the battlefield as a crime scene.

Forensic Perspectives in the Ramayana

The Ramayana, the epic tale of Lord Rama’s religious journey, also contains instances where the establishment of truth and justice depends on careful observation and interpretation of events. “Lord Rama often relied on advice and evidence before making decisions. This reflects an early understanding of jurisprudence. His approach resonates strongly with the fundamental principles of modern forensic science and criminal investigation. In contemporary investigations, evidence is the cornerstone of the search for truth. Just as Lord Rama sought confirmation before acting, modern forensic experts collect, preserve, and analyze physical evidence to reconstruct events and reach unbiased conclusions. Whether it’s DNA, fingerprints, toxicology reports, or trace material, every piece of evidence acts as a silent witness, leading investigators to objective conclusions. Shri Rama’s reliance on advice parallels the multidisciplinary approach seen today, where forensic scientists collaborate to ensure that justice is both thorough and fair. The abduction of Sita by Ravana sets up the central conflict of the Ramayana. The extensive search undertaken by Lord Rama and his associates is a striking example of early investigative methods. They began by gathering information from various sources, including Jatayu. These included eyewitness accounts and information from local creatures—birds, animals, sages, and forest dwellers. This is much like how modern investigators gather tips from informants and witnesses to build initial leads.

When Ravana abducted Sita and was taking her through the sky, Sita displayed unparalleled wisdom and immense hope. She dropped her ornaments one by one along the path—this act was not merely an emotional reaction, but a well-planned effort to convey her message to Lord Rama. This is a remarkable example of the self-confidence of women of that time, their ability to maintain composure in times of crisis, and their ability to make informed decisions.

The discovery of these fallen ornaments was not a simple search for objects, but a kind of “evidence-gathering process”—proving to be the first crucial clue indicating Sita’s location, the direction of her abduction, and Ravana’s possible route.

These ornaments serve as physical evidence in the modern context. Just as today’s explorers or trackers infer routes based on vegetation, footprints, or discarded clothing, Rama and the monkey army analyzed these ornaments and other environmental clues. These clues not only confirmed Ravana’s abduction of Sita but also indicated the direction in which he might have gone.

Based on these clues, with the help of the monkey commander Sugriva and allies like Hanuman, the journey to Lanka was paved. This entire endeavor illustrates how a woman’s hope, signs left in the form of symbols, and the watchful eyes of explorers can combine to lead to a difficult truth.After the clues obtained from Sita’s jewelry, the next crucial phase of the Ramayana’s journey of discovery was Hanuman’s solo journey to Lanka. This was not merely an adventure, but a well-organized and goal-driven intelligence mission, demonstrating a masterful strategy for gathering information, analyzing it, and then presenting it at the right time.

Hanuman’s journey was a deep and careful observation of the city of Lanka, its people, military system, and most importantly—the condition and mental state of Sita. He not only studied the strength of Ravana’s army, Lanka’s geographical structure, and security system, but also established contact with Sita and confirmed her state of mind, patience, and survival. Conveying these facts to Lord Rama was the central objective of his mission.

Hanuman’s direct observations and the report he gave to Ram were like a crucial intelligence document—full of detail, accuracy, and strategic insights. They not only confirmed Sita’s location but also revealed her mental resilience and the mental torture she was facing at the hands of Ravana.

This entire process—gathering information, analyzing it, and then transforming it into a strategy—is similar to the fundamental principles of modern forensic science and intelligence investigation. Just as a spy or forensic expert collects evidence during a mission, analyzes the location, and then makes decisions based on their report, Hanuman acted in the same way.

His journey and report formed the basis on which the entire construction of the Ram Setu, the military planning, and the strategy for the invasion of Lanka were developed.

Arthashastra: A Proto-Forensic Legal Framework

The Arthashastra, written by Kautilya, is a unique text in the Indian legal and administrative tradition, often considered a guide to politics, diplomacy, and statecraft. However, its relevance is not limited to administrative and political perspectives; it also offers a profound perspective on topics such as crime classification, criminal investigation, judicial procedures, intelligence systems, and toxicology. The methods described in this text for identifying, investigating, and judging crimes in ancient India bear striking resemblance to modern forensic science and the criminal justice system today.

The Arthashastra not only systematically explains crimes such as theft, murder, perjury, betrayal, and poisoning, but also adopts a scientific approach to their investigation. For example, the method of comparing footprints found at a crime scene with the gait, footwear, or measurements of suspects is clearly mentioned. This can be seen as the foundation of trace evidence and crime scene analysis, which are currently in use. Similarly, in examining witnesses, their statements alone were not considered sufficient; rather, a thorough examination of their social status, past credibility, and the logical consistency of their statements was considered essential. This process is analogous to the testing of the credibility of testimony in the modern legal system.

Kautilya’s thinking regarding the intelligence system was also very advanced. He proposed an extensive system of disguised spies who, like undercover agents, monitored suspicious activities and provided information to the state. This system appears to be the foundation of the modern intelligence surveillance system. Kautilya’s approach to justice was purely evidence-based. He believed that justice should be based on reasonable evidence, not just punishment. He mentioned four types of evidence—lekhya (documents), sakshi (testimony), avesha (confession), and sashaya (circumstantial evidence). This classification closely resembles the categories of evidence accepted in the modern judicial system. The role of the judge is also described as impartial, judicious, and lawful, which is the fundamental criterion for judicial conduct today. Kautilya’s understanding of toxicology was highly scientific and practical. He classified poisons into four major categories: plant-borne poisons (such as aak, karveer, dhatura), animal-borne poisons (snake, scorpion, etc.), mineral poisons (mercury, orpiment, and raskarkapoor), and combined poisons, which were prepared by mixing various elements. Various means of poisoning are also mentioned, such as through food, perfume, jewelry, clothing, or contact with women. This not only reflects the socio-political complexities of the use of poisons but also reveals the profound level of chemical knowledge in ancient India. Kautilya mentions characteristic tests for identifying poisoning, such as changes in skin color, abnormalities of the eyes, vomiting or foaming at the mouth, and the suddenness of death. Testing an object on animals and birds to confirm its toxicity can be considered the archetype of today’s bioassay. Furthermore, the concept of “Visha Kanya” (poison girls) is also found in the Arthashastra, where women were used as instruments of secret murder by being accustom to poison. It also describes antidotes and preventative measures to counteract the effects of poison.

Thus, the Arthashastra is not only a political treatise but also a highly significant treatise on justice, forensics, and toxicology. This treatise demonstrates the profound integration of law and science in ancient India, a relevance that is clearly reflected in modern legal and forensic systems. Kautilya’s judicial and scientific approach, evidence-based mechanisms, and intelligence system are not only historically significant but also make him memorable in contemporary legal discourse.

Conclusion

Through extensive research and careful consideration of ancient Indian texts and historical events, it becomes clear that Indian civilization developed concepts of justice, crime, and the forensic process long ago. The analysis of events, the collection of evidence, and the procedures for investigating crimes in epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata closely resemble modern forensic principles.The loss of Sita’s ornaments and Hanuman’s journey to Lanka demonstrate that reconstructing events and making decisions based on clues, evidence, and observations was a well-planned and scientific process. Similarly, Kautilya’s Arthashastra was not only a political or administrative treatise, but also a remarkable example of the judicial and legal systems of ancient Indian society. The methods for investigating crimes, the principles of evidence collection, and the process of administering justice it describes are highly consistent with modern judicial and legal science.

These principles and methods of ancient India are proof that our ancestors deeply and systematically valued the judicial structure of society and the investigation of crimes. This not only demonstrates the strength of their judicial system, but also proves that the foundations of forensic approaches and legal analysis were laid long ago.

References

- Tiwari, B.N. (2017). Ancient India

- Tiwari, P. V. (2020). Ancient Indian Forensics. Bharatiya Vidya Mandir.

- Yasa, V. (2008). Mahabharata (C. S. S. S. S. Sharma, Trans.). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Matilal, B. K. (1998). The Word and the World: India’s Contribution to the Study of Language. Oxford University Press.

- Kapoor, K. (2004). Ancient Indian Literary Theory and Jurisprudence. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA).

- Kangle, R. P. (1963). The Kautiliya Arthashastra: Part II – An English Translation with Critical and Explanatory Notes. Bombay University.

- Gode, P. K. (1956). Studies in Indian Cultural History (Vol. II).

- Law, N. N. (1914). Studies in Ancient Indian Law.

- Altekar, A. S. (1958). State and Government in Ancient India.

- Mishra, B. N. (2000). Criminal Law and Justice in Ancient India.

- Sankayo. (2016, August 24). The wheel turns…nothing is ever new. Indus.heartstrings. Retrieved from https://indus.heartstrings.blog/the-wheel-turns