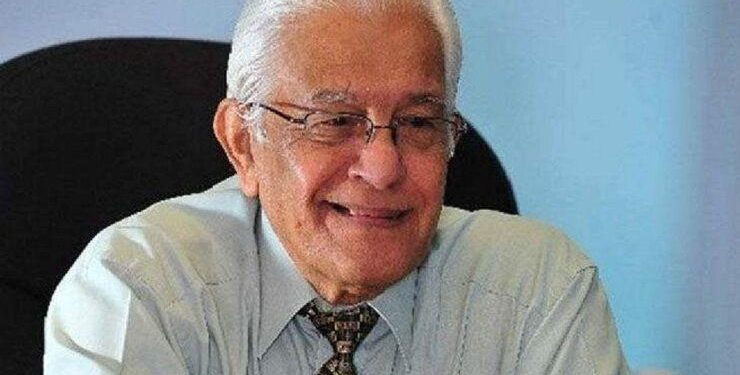

From JAI PARASRAM

For those of us who have known Basdeo Panday for decades (I first met him in 1972), it is sad passing for a man who struggled for decades to uplift the poor, downtrodden and the dispossessed.

I followed his long political career and had the privilege of working closely with him in his various political incarnations and also when he was Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago. I was fortunate to know him and report on his political activities as a journalist and later, as a political communications adviser.

When Panday entered electoral politics in 1966 the PNM was well entrenched in government. He shunned racial politics, ran for a social democratic party – The Workers and Farmers Party – in an Indian constituency and lost to the DLP candidate.

But he didn’t disappear from the national scene. In the early seventies he returned to service with the death of Bhadase Maraj and became the new Hindu/Trade Union leader in the Indian heartland in the sugar belt. Panday used the union as a base to build support for a political movement.

While he believed in a new type of politics, based on equality and respect for one another, regardless of race, religion or social standing, he would inevitably have to lean heavily on ethnic voting.

Still he believed national unity was the way to go. As an opposition senator in 1972 he placed on record a reality that was to guide his politics throughout his career.

“Ours is too small a country,” he told the Senate on September 15th, 1972, “to try to discriminate against each other. We are too dependent on one another and once you discriminate against one another you damage the entire country.”

In 1975 Panday’s sugar union joined all the country’s major trade unions in a rally of solidarity from which emerged a new political party, the United Labour Front (ULF).

In the General Election of 1976 the ULF made a significant breakthrough with 10 of the 36 seats in Parliament, replacing the Indian-based DLP. The victory was also a major disappointment for Panday who did not get the support of the entire working class, especially the predominantly black workers in the oil industry.

He told me in an interview it was because the nation was prepared to unite on labour and social issues but it was not mature enough to do the same in politics.

Five years later he formed an opposition alliance with the ULF, Tapia, headed by economist Lloyd Best and The Democratic Action Congress (DAC) led by A.N.R. Robinson, which had won the two Tobago seats in the 1976 Parliament.

In that year a new conservative party – the Organization for National Reconstruction (ONR) – led by former PNM Attorney General Karl Hudson Phillips became the main opposition challenger. With the Alliance and ONR as the opposition, the PNM scored an easy victory.

But it was Panday who went back to Parliament as opposition leader (The ONR didn’t win a seat) from where he continued his efforts to build a national party based on embracing people of all races, classes and religions.

The result was a unitary party comprising all the other opposition groups. Panday as the leader with the largest block of MPs in Parliament could have easily emerged as the leader of the new National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR).

But he was convinced based on his earlier political losses that the nation was not ready to accept an Indian leader as Prime Minister. So he handed the leadership of the infant party to the DAC leader Arthur N. Robinson.

In the general election of December 15, 1986 his dream became a reality when the NAR won a landslide with 33 of the 36 seats in Parliament, sweeping the PNM out of office after 30 consecutive years in power.

But it soon turned into a nightmare as conflicts developed within the ‘one-love’ movement based on race and policy issues. The massive majority gave Robinson the clout to ignore Panday, knowing that he would keep a majority even if Panday left.

And that is what happened, although some of the seats giving him the majority were rightfully those of Panday’s ULF. Panday and some of his loyalists quit.

The others stayed, including Winston Dookeran, who later came back to Panday’s political camp, then left again and and formed the Congress of the People (COP), which was the movement that Panday blamed for the loss of the 2007 election.

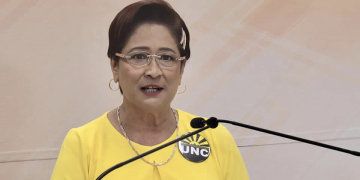

The break with the NAR led to the formation of CLUB 88 (Committee of Love, Unity and Brotherhood) and the birth of the United National Congress (UNC), which Panday described as a movement that would attract people not because of the “colour of their skins but the content of their minds.”

Panday’s nationalism – unlike that of Eric Williams, Robinson et al – had always been based on embracing Trinidad and Tobago’s diversity and celebrating its plurality.

Panday survived the political roller coaster and continued his struggle for democracy, freedom and justice on behalf of a constituency that still yearns for these fundamental human rights decades after Trinidad and Tobago’s leaders pulled down the Union Jack and gave birth to a nation, seeking God’s blessings for a land forged “from the love of liberty”, promising equality for every creed and race.

His constituency comprised mainly those whose voices had been muffled in the din of political expediency.

Panday was the man who called the nation’s attention to the injustices that workers suffered under the Williams PNM administration. He walked shoulder-to-shoulder with George Weekes, Raffique Shah, Joe Young, other labour leaders and politicians on Bloody Tuesday – March 18, 1976 – to demand justice for the working class.

And though he was brutalized and jailed he remained committed to the same cause for which he fought throughout his political career: freedom, equality and justice. I was there on bloody Tuesday and saw him brutalized. Tonight I grieve with his family and everyone who loved the CHIEF.

Panday frequently reminded his inner circle that “his people” comprised everyone, people of every race, religion, class and colour, in every village and town. “Hunger doesn’t have a colour,” he once said, adding that poverty “doesn’t have a religion.”

His greatest passion had been for uniting the people, for building a meritocracy in which everybody would be a first-class citizen unlike the one that the late Lloyd Best once described, where “everyone felt like a third-class citizen.”

Panday’s philosophy had always been the same – that any party that chooses to represent only one group is doomed because the nation’s plurality and diversity make it necessary for a government to include everyone.

When Patrick Manning assumed office in 2001 by presidential decree, pushing Panday from Prime Minister to Opposition leader, Manning tried unsuccessfully to push the UNC back to the sugar cane fields by taking the cane fields away from the UNC. He left the UNC without its primary constituency in the hope that instead of rising from the ashes, the UNC would retreat to a “comfort zone” of marginal politics.

But Panday refused to ride into the sunset and go away and continued his struggle with a renewed urgency and an even deeper sense of national unity.

And he wrapped up the 2007 campaign at the birthplace of the UNC in Aranguez, announcing that it would be his last political battle. He urged everyone to remain united.

“I remember my struggle to unite this country…I have no regrets. As I come to the end of a very long journey I ask you to send me off in a blaze of glory” he said. “Stand tall!” he declared, “Bow to no one.”

His earthly journey is finally at an end. And those of us knew and loved him will miss his passion and his wit.

January 2010 marked the end of his active political career as leader of the United National Congress. Today he was called home to continue the rest of the journey of his soul.

OM SADGATI.