Published by COHA; re-published because of current public interest

Several Weeks ago, COHA published an analysis of the Venezuela-Guyana boundary dispute by guest scholar Eva Golinger, who is a New York-based attorney and the author of the best-selling book The Chavez Code. In her article, Golinger presents a distinctively pro-Venezuela perspective. In an effort to create a constructive forum between two longtime friends of the organization, COHA is re-publishing the following piece by Dr. Odeen Ishmael. Mr. Ishmael served as Guyana’s ambassador to Washington and now serves as a COHA Senior Research Fellow. His piece presents a strongly pro-Guyana perspective and, as such, will serve to add balance to this issue.

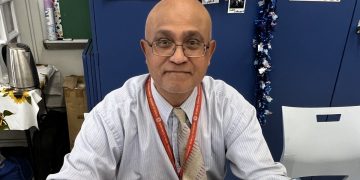

By: Dr. Odeen Ishmael, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Ever so often, sections of the local and foreign media propagate the erroneous idea of an existing territorial “dispute” between Venezuela and Guyana over the Essequibo region. They report about the “disputed” oil-rich Essequibo territory, conveniently ignoring the fact that the territory was firmly defined as Guyana’s by the international arbitral award of October 1899. Actually, what has existed since 1962 is a spurious and illegal claim by Venezuela to Guyana’s disputed territory. In that year, Venezuela assumed the right to unilaterally pronounce that the award was “null and void” and ventured to declare ownership over roughly two-thirds of Guyana’s territory. The area included all territory west of the Essequibo River, except for a narrow strip east of a straight line stretching from the mouth of the Pomeroon River to the confluence of the Mazaruni and the Essequibo Rivers. In later years, Venezuela expanded this claim to include this strip, along with the islands in the Essequibo River.

Treaty of Washington, 1897

Up to the time of the arbitration, Venezuela claimed almost all the territory west of the Essequibo River, including an area which is now Brazilian territory. Acting for British Guiana, Great Britain counter-claimed as its sovereign territory not only the area claimed by Venezuela, but also the upper Cuyuni basin and a swath of land in the Amakura and Barima basins up the right bank of the Orinoco River. The territorial arbitration was demanded by Venezuela with the heavy backing, from 1895, of the United States government which even threatened war on the British if they refused to retract their claims. After intense negotiations, Venezuela and Great Britain signed the Treaty of Washington on February 2, 1897, by which they agreed to place the contending claims to territory by both sides to a tribunal comprising of five judges—two appointed by the British, two by the Venezuelans and the fifth, to be the president of the tribunal, chosen by the other four. The treaty also specified that the two countries agreed “to consider the result of the tribunal of arbitration as a full, perfect, and final settlement of all the questions referred to the arbitrators.” [Treaty of Washington, Article XIII, February 2, 1897]

Earlier, on November 12, 1896 in Washington, Sir Julian Pauncefote, the British ambassador, and US Secretary of State Richard Olney—who vigorously championed Venezuela’s territorial claim—signed a protocol which set out the main terms of the treaty signed between the two countries.

The arbitration treaty was enthusiastically welcomed by the Venezuelan government, and on February 20, 1897, President Joaquín de Jesús Crespo, in a message to the Venezuelan Congress, dutifully thanked US President Grover Cleveland and Olney for their “laudable efforts” to push the British government “to accept arbitration unreservedly and unconditionally . . . in order to adjust, with greater facility and success, this unpleasant dispute of almost a century.”

In praising American support for Venezuela, he proclaimed that arbitration “would put an end to the old dispute between the two nations.” He especially thanked Olney who “generously interposed in this dispute, seeking an arrangement which would at once preserve the laws of the national decorum and the continental integrity.”

He added: “The recourse to arbitration offered itself, and, although by no means in the manner wished for by Venezuela, was more consonant than any other with the desires manifested. The government deemed it proper to insert in the treaty a provision that Venezuela should have a voice in the naming of the arbitral tribunal. As soon as this change was proposed, its acceptance was procured. The action of the United States had produced a result the after effects or which were, from a moral point of view, indispensably subject to the effective and powerful prestige of said nation.” [The New York Times, March 12, 1897]

Shortly after President Crespo’s presentation, the Venezuelan Congress ratified the arbitration treaty and offered its full support to the arbitral tribunal.

The tribunal and the award

The arbitral tribunal was finally set up in 1898 and began to receive written submissions from Venezuela and Great Britain. Oral presentations were made by the legal team on each side from June to September 1899 and finally, on October 3, the tribunal announced its award by upholding Great Britain’s ownership of most of the claimed territory west of the Essequibo River but denying the British entitlement to the upper Cuyuni basin and an area of land on the eastern bank near the mouth of the Orinoco River. Thus ended the dispute which had existed since 1840.

The territory awarded to the British (on behalf of colonial British Guiana) included a 4,000 square-mile block south of the Pakaraima Mountains bordered by the Cotinga River on the west, the Takutu River on the south and the Ireng River on the east and north. (This portion of territory, originally claimed by Venezuela in its case before the arbitral tribunal, was awarded to Brazil on June 6, 1904, following another arbitration conducted by the King of Italy after the Brazilian government claimed ownership based on historical occupation. When Venezuela in 1962 renewed its claim to the territory west of the Essequibo River on its alleged grounds that the 1899 award was null and void, that nation did not make any claim—and has never since made any—to that section of territory awarded to Brazil.)

Both Venezuela and Great Britain accepted the award of the tribunal and, in keeping with it, a mixed boundary commission appointed jointly by the two countries, carried out a survey and demarcation, between 1901 and 1905, of the boundary as stipulated by the award with an adjustment based on the British Guiana-Brazilian arbitration award.

The resulting boundary line was set out on a map signed by the boundary commissioners in Georgetown, British Guiana, on January 7, 1905. A separate agreement signed three days later by the commissioners stipulated: “That they regard this agreement as having a perfectly official character with respect to the acts and rights of both governments in the territory demarcated. . .” [Agreement Between the British and Venezuelan Boundary Commissioners with Regard to the Map of the Boundary, January 10, 1905]

Twenty-six years later, in 1931, a boundary commission made up of representatives from Great Britain, Venezuela and Brazil made special astronomical, geodesical and topographical observations on Mount Roraima so as to fix the specific point where the boundaries of Brazil, Venezuela and British Guiana should meet. Diplomatic notes were exchanged among the three nations on October 7 and November 3, 1932, by which they expressed agreement on the specific location of the tri-junction meeting point of the boundaries. A concrete pyramid marker was soon after erected there. The matter of the border was then considered permanently settled.

Significantly, by its rejection of the 1899 arbitral award, Venezuela has also unilaterally thrown out its own tripartite agreement of 1932 with Brazil that the peak of Mount Roraima forms the meeting point of the boundaries between those countries and Guyana.

Venezuela’s renewed claim

It was clear that Venezuela had accepted the 1899 award as a final settlement of the border dispute. Even as late as 1941, the Venezuelan minister of foreign affairs, Esteban Gil Borges, agreed that the frontier with British Guiana was well defined and was a closed issue.

Indeed in that year, Borges told the British representative in Caracas that his government was definitely of the opinion that the boundary question was a chose jugeé, that the Venezuelan‑British Guiana frontier was final and well defined, and that the author of articles in the Venezuelan press about that time, questioning the 1899 award, “had obviously never had access to the archives of his ministry.” [Guyana Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, December 1968]

However, in February 1944, forty-five years after the arbitral award, Severo Mallet-Prevost, one of the four lawyers who represented Venezuela before the arbitral tribunal, wrote a memorandum in which, for the first time, he attacked the award on the alleged grounds that it was the result of a political deal between Great Britain and Russia. However, he refused to make the memorandum public and instructed that it should not be published until after his death. The memorandum was finally published by his associate, Dr. Otto Schoenrich, in the American Journal of International Law, Volume 43, Number 3, of July 1949.

Despite the rumblings in Venezuela over Mallet-Prevost’s unproved allegations, the Venezuelan government willingly accepted the arbitral award and fully honored it until 1962. In that year, Venezuela, basing new arguments on the Mallet-Prevost memorandum, declared that the 1899 arbitral award was “null and void” and again resuscitated its pre-1899 claim to almost all the area west of the Essequibo River—comprising about 50,000 square miles representing roughly two-thirds of Guyana’s territory.

Records were again examined, and although Venezuela could not produce any document to prove its claim, the governments of Venezuela, Great Britain, and British Guiana, in February 1966, signed an agreement in Geneva, Switzerland, by which a bilateral commission was appointed to seek “satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom which has arisen as the result of the Venezuelan contention that the arbitral award of 1899 about the frontier between British Guiana and Venezuela is null and void.” [Geneva Agreement, Article V, February 1966]

Historical background of Geneva Agreement, 1966

Looking back to the period immediately before 1966, a meeting in London between Venezuelan and British representatives (along with a representative from British Guiana) was held on November 7, 1965. This negotiation session issued a joint communiqué saying that both sides should work to: “Find satisfactory solutions for a practical settlement of the controversy which has arisen as a result of the Venezuelan contention that the 1899 award is null and void.”

A follow-up high level meeting was held between the Venezuelan foreign minister, on the one part, and the British Secretary of State for foreign affairs and the premier of British Guiana, on the other, on December 9-10, 1965. Based on the November communiqué, one of the agenda items for this meeting was listed as: “Find satisfactory solutions for a practical settlement of the controversy which has arisen as a result of the Venezuelan contention that the 1899 Award is null and void.”

With regard to the Geneva Agreement of 1966, Article I established a Mixed Commission to seek “satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom which has arisen as a result of the Venezuelan contention that the Arbitral Award of 1899 about the frontier between British Guiana and Venezuela is null and void”.

Significantly, the wording of the November 1965 joint communiqué and the Geneva Agreement on this specific issue is identical. Obviously, this language specified that the parties should continue to investigation and research the issue to determine if there were any grounds to support nullity of the arbitral award of 1899.

Evidently, this could not mean that the United Kingdom, British Guiana and Venezuela had agreed that the border between British Guiana and Venezuela should be revised. All it allowed for was to facilitate an examination of documents in order to put the Venezuelan contention to rest.

Over the years, since 1966, Venezuela has spread the propaganda that the arbitral award is null and void. By doing so, Venezuela contradicts the terms of the Geneva Agreement. And more recently, it has been expressing the view that the “territorial dispute” is “inherited from British colonialism.” The view is patently false since the land boundary between Guyana and Venezuela was permanently and definitively delimited by the international arbitration on October 3, 1899. As recent as July 27, 2015, Venezuelan foreign minister Delcy Rodríguez, according to a report in the Venezuelan newspaper, El Universal, claimed that the “controversy has been ongoing for some two hundred years,” conveniently falsifying the historical fact that the controversy began in 1962 when Venezuela resuscitated it claim to territory awarded to Guyana by international arbitration sixty-three years before.

Venezuela has also presented as its claim to nullity of the award, the excuse being that it had no Venezuelan judges and lawyers as its representatives in the tribunal’s hearings. On September 28, 1982, the Venezuelan foreign minister, in an address to the UN General Assembly, characterized the 1899 award as an “extraordinary farce from a so-called court of arbitration without Venezuelan judges and lawyers.”

However, in an immediate response, Guyana’s permanent representative to the UN, Ambassador Noel Sinclair, told reporters that the absence of Venezuelan judges or lawyers came about because Venezuela decided to have its interests represented by US jurists since it was confident that they would represent Venezuela’s interests very well.

The fact remains that Venezuela placed its trust in two American senior judges and four American lawyers to argue its case before the arbitration tribunal. Ironically, while it bemoans the absence of Venezuelan jurists, it unabashedly has now placed its trust on the unproven allegations of one member of its legal team, the American lawyer Severo Mallet-Prevost who waited forty-five years after the arbitral award to claim that the British judges colluded with the Russian judge, who was the chairman of the tribunal, to rule more in favor of the British case. Interestingly, the most senior lawyer who argued the Venezuelan case, former US President Benjamin Harrison, in none of his writings mentioned any such allegations as did his junior partner.

Clearly, the “solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy” has nothing to do with any so-called “dispute” about the border between Guyana and Venezuela. The “solutions” specifically relate to a resolution of the “controversy” arising out of Venezuela’s contention that the arbitral award is null and void.

What must also be noted is that the arbitral award was the final result of the Treaty of Washington 1897, signed by the United Kingdom and Venezuela. To claim that the arbitral award is null is contradicting the Treaty of Washington as well. And, actually, the Venezuelan government is contravening its own legislation by exhibiting its opposition to its own congressional ratification of the Treaty of Washington back in 1897.

Venezuela has not raised any objection to this treaty so it is bound by it. The arbitral award cannot be nullified by the statement of one party; this can only be done by a judicial process or by mutual agreement between all the parties involved. Since Venezuela challenges the award, it is for that country to establish its case before an international judicial tribunal that the award is null and void. So far, Venezuela has not attempted to do so and, more recently, has again refused to agree with Guyana for the issue to be dealt with by the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

In misinterpreting the Geneva Agreement, Venezuela has also argued that the “practical settlement of the controversy” means a settlement of the border by which Guyana cedes territory to Venezuela. The term “practical settlement of the controversy” clearly indicates a practical settlement of the issue relating to the alleged nullity of the arbitral award. It means the inspection of documents as was started before 1966, and nothing more.

What must also be borne in mind is that Article VIII of the Geneva Agreement states very clearly that the British government remains an equal party to the treaty. Great Britain never has handed over its rights as a party to the Guyana government, and must, therefore, play an active role in resisting any claim by Venezuela to Guyana’s territory.

The Geneva Agreement also stipulates that “no new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim to territorial sovereignty in those territories, shall be asserted while this agreement is in force. . .” Undoubtedly, Venezuela has breached this agreement since it vociferously expresses a new claim to Guyana’s maritime space soon after the American oil company, Exxon Mobil, announced the discovery of immense quantities of crude petroleum in the area.

Interpreting the Geneva Agreement

The aim of the Geneva Agreement was to afford Venezuela an opportunity in essentially a bilateral context to examine its contention of a nullity to be found in the 1899 award.

In the maintenance by Venezuela of its claim, the Geneva Agreement was also a logical part of the process of examination of documentary material establishing a nullity, being found in the Venezuelan case to that would produce such evidence. But there was an important difference. The Geneva Agreement, unlike “an offer,” was now an international treaty that was legally binding. Thus, it provided an agreed legal mechanism for continuing the process started in 1963, that is, of examining the Venezuelan contention of the existence of a nullity in the 1899 award.

The provisions of the Geneva Agreement also maintained the position taken by the British in 1962, that is, the agreement was in no way related to substantive talks about the revision of the frontier. The agreement was therefore a legal basis for dealing with the political situation caused by Venezuelan revanchism in maintaining a claim to two-thirds of Guyana’s territory.

From the beginning, Venezuela ignored the main role of the agreement under which a Mixed Commission was established to deal with the Venezuelan contention a nullity in the 1899 award. The commission was given a maximum of four years to complete its task.

At the very first meeting of the commission, the Venezuelan commissioners were invited by their Guyanese counterparts to produce evidence to support their contention of a nullity. However, the Venezuelans took the position that the commission should not be concerned with such a question but rather with the revision of the frontier. However, the Geneva Agreement never allowed for such a demand. The Mixed Commission, in subsequent meetings, was unable to fulfill its mandate largely because Venezuela declined to deal with the question of their contention of the nullity of the 1899 Award.

In citing the Geneva Agreement, especially Article I, the government of Venezuela attempted at subsequent meetings of the Mixed Commission to limit the scope and application of the Geneva Agreement. Venezuelan officials emphasized on the words “the practical settlement of the controversy” to the exclusion of all other phrases in the relevant provisions. Shortly after, they began to describe the issue as a “territorial controversy.”

However, Guyana stated that there was no “territorial controversy”—only a controversy over the contention by Venezuela of the invalidity of that the arbitral award of 1899.

According to the Guyana government, in any discussion with a view to finding a solution to any controversy, Venezuela must agree that the prior issue to be discussed was its contention of the nullity of the 1899 award.

Current position

Until the start of 2015, it has been the policy of the Guyana government not to make any proposals for a solution of the “controversy” since 1982 when the UN Secretary General was requested by both countries to decide on a method of solution. This is understandable given the fact that Guyana has always maintained that a full, perfect and final settlement was already reached in 1899. However, the Geneva Agreement of 1966 has helped, at least in the eyes of Venezuelans, in elevating Venezuela’s renewed claim. Successive Venezuelan administrations have since then interpreted the agreement to mean that discussions should follow to revise the frontier based on their country’s claim on the entire western Essequibo.

The involvement of the UN Secretary General including his appointment, in 1990, of a “good officer” to find a solution to the controversy, has failed to show any success. As a result, in December 2014, Guyana stated that it would opt out of the UN “good officer” process and proposed that that the ICJ should be allowed to find a solution. However, Venezuela has expressed its opposition to this proposal saying that the UN Secretary General must continue to handle the matter.

Despite all its claims to Guyana’s territory, it became apparent that the Venezuelan government knew that it had no solid grounds to stand on. This was exemplified for the first time of June 23, 1982, when Dr. Sadio Garavini, the Venezuelan Ambassador to Guyana, stated at a press conference at his embassy that the only solution to the issue would involve ceding of some land by Guyana. He insisted that his government no longer intended to demand all the land it was originally claiming. This idea of not pursuing the territorial demand to its entirety, thus, added a new dimension to the situation.

Actually, a similar Venezuelan view was expressed eighteen years later. On August 7, 2000, Oliver Jackman, the UN Secretary General’s personal representative, at a meeting with Guyana’s foreign minister in Georgetown, stated that during a visit to Caracas a few days before he asked President Chavez what Venezuela meant by a “practical settlement of the controversy”—whether Guyana would have to cede territory to Venezuela. According to Jackman, the Venezuelan president said that Guyana did not have to cede “the whole thing” and that a solution of the contention would involve Guyana’s cession of “part of the Essequibo region.”

However, in recent times, conflicting signals coming out of Venezuela give the impression that the Venezuelan government is not too confident with the claim. Some Venezuelan legal analysts have also stated that the Venezuelan claim no longer exists saying that ended when President Chavez declared in February 2004 that Venezuela would no longer object to Guyana’s investment in projects in western Essequibo.

More recently, Venezuelan officials have begun to promote the idea that the solution to the border issue can be generated through the South American integration process. Elias Daniels, who headed the special Guyana unit in the Venezuelan foreign ministry, said that the multilateral and bilateral meetings under the South American integration process “may help to find a solution to the Essequibo controversy.” Significantly, (as reported in El Universal on June 16, 2005), he added, “the chancellery [foreign affairs ministry] has not been able to compile sufficient grounds which would permit it to uphold its arguments on the rights of Venezuelan sovereignty over Essequibo.”

Then in March 2015, President Nicolás Maduro took a more aggressive stance by declaring ownership of much of Guyana’s maritime space after Exxon Mobil discovered immense quantities of petroleum in the area. After Guyana denounced this new Venezuelan claim, statements emanating from the Venezuelan government declared that country’s “historic right” over the Essequibo and waters offshore.

Then in March 2015, President Nicolás Maduro took a more aggressive stance by declaring ownership of much of Guyana’s maritime space after Exxon Mobil discovered immense quantities of petroleum in the area. After Guyana denounced this new Venezuelan claim, statements emanating from the Venezuelan government declared that country’s “historic right” over the Essequibo and waters offshore.

What if the award is legally nullified?

So far, Venezuela has continued to express its disinterest in agreeing for the issue to be dealt with by the ICJ in order to determine once and for all the legality, or otherwise, of the 1899 award. But even if the award, along with the 1897 Treaty of Washington, is nullified by the ICJ, that does not mean that the land claimed by Venezuela automatically becomes its property. In such a situation, whatever settlement procedure is adopted, account will have to be taken of all the claims of both sides, including in particular, claims by Guyana to the Amakura, Barima and Cuyuni areas, which were lost to Venezuela as a result of the award; and also claims by Guyana based upon possession and occupation right up to 1962 when Venezuela first formally rejected the validity of the 1899 award. But even before any peaceful new solution is arrived at, a new treaty of arbitration will have to be negotiated. And if, perchance, any new arbitration should issue an award more favorable to Guyana, will Venezuela accept it? This will be very doubtful since Venezuela has historically, by its rejection of the internationally binding award of 1899, shown a propensity of not accepting a decision when it feels that such a decision is not in its national interest.

But will Venezuela be ever satisfied if the 1899 award is nullified? Surely, such a development will create a new legal precedence and will allow for legal challenges to existing boundary agreements with other neighboring countries, including Colombia, Brazil, the Netherland Antilles, Trinidad and Tobago and island states of the Eastern Caribbean. Wider afield, it will also allow various countries to legally challenge their long-existing boundary treaties with which they became dissatisfied. Obviously, such a situation will create a volatile state of affairs that can present a serious threat to international peace and security—a situation which the international community will not ever want to face.

By: Dr. Odeen Ishmael, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

[Dr. Odeen Ishmael, Ambassador Emeritus (retired), historian and author, served as Guyana’s ambassador in the USA (1993-2003), Venezuela 2003-2011) and Kuwait (2011-2014). He is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the Washington-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs. He is the author of the The Trail of Diplomacy – The Guyana-Venezuela Border Issue (in three volumes.)]

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.