By S. Kumar and R. Kumar

Introduction

The struggles and toil of Girmitiyas is well known and documented. This short paper analyses the link between the population growth, economic progress and the struggles ofIndo-Fijians over the last one hundred and forty years since the day the indentured labourers set their foot on Fiji. We analyse the population growth trends of Indo-Fijians and link that with political conflict,migration trends over the years and their economic wellbeing. Right now the Indo-Fijians are a happy lot despite their past tribulations and troubles. However, thenet population growth of Indo-Fijians is currently negative (population is declining), for which there are two reasons: 1) thefertility rate among Indo-Fijian women has fallen significantly; and 2) outward migration of Indo-Fijians has continued unabated since 1987. The population growth has remained negative since 1987 but the outward migration of Indians started since 1950s. This decline in population growth has had two determinant outcomes. First, the fear among i-Taukei (Native Fijians) of Indo-Fijian political dominance has diminished and second, the economic status of Indo-Fijians has improved significantly. The second outcome here mentioned is however linked to various other factors such as lower dependency ratio of Indo-Fijian families and better (determined) access to education, and thus greater incidence of employment and economic certainty.

Despite this progress, a significant proportion of Indo-Fijian population (~19%) continue to live in pockets of poverty. In some cases, however, they suffer severeinstances of poverty traits, such as food poverty or chronic poverty. The nature of poverty among Indo-Fijians could intensify if the macroeconomic conditions in Fiji doesnot improve quickly after the current Covid-19 downturn. The post-COVID-19 global order may pose serious challenges for Fiji if the government did not take of board appropriate steps to implement economic reforms and change course to create new economic sectorsand bump upeconomic output.

Brief History of Indo-Fijians

As everywhere in the British colonies, labour shortages prompted the British to source labour from its erstwhile colony, India. The end of slavery in the British colonies in 1834 created a huge shortage of workers, which prompted the indenture system of labour movement into the colonies and it proved lucrative for the British colonial administration everywhere from Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Mauritius and South Africa to Fiji. As everywhere, indentured Indians in Fiji worked under the indenture labour system of the British colonial government for nearly 40 years. In this period,60,965Indian indentured labourers were brought into the colony. While the indenture in Mauritius started in 1834, in Trinidad and Tobago in 1845, it started in Fiji much later in 1879 and continued until 1916. A total of 1.2 million Indians travelled out as indentured labourers into the British colonies during this period.

As in Trinidad and Tobago, Sir Arthur Gordon was the also the first substantive governor of colonial Fiji from 1875-80. He realised that the colony had great economic prospect for sugarcane and cotton wool,which prompted the urgent need of farm labour. The natives of Fiji under Arthur Gordon’s government were prevented from working on the sugar plantations.Therefore, to meet theurgent labour need, Sir Arthur Gordon decided to import Indians under the indenture system since importing Melanesianor Polynesian labour was not as profitable amid criticisms of the cruel blackbirding practices of the time.As documented by many writers and historians, the indentured system of labour engagement was extremely beneficial for the colonial government. The system was hugely profitable for the CSR Company of Australia.Therefore, Sir Arthur Gordon, having worked with the Indians in the other British colonies was encouraged to import as much indentured Indians as possible.

The endeavour of importing Indians under the indentured system thus was entirely profit driven without much concern or regard to human or social dimensions.

Indian Population in the Post Indenture Period

With the profit motive of the CSR Company,more and more ships of Indian immigrants came into Fiji, totalling around 61,000, which was an overwhelming phenomenon for the native people. By 1920, the population of Indian indentured labourers reached around 40% of the total. The population thereafter continued to increase rapidly surpassing 50% in 1966. During the period 1940-60 political narratives and rhetoric was much distressing and racially charged. While the Britishcontinued to govern, the colony felt threatened by the very new foreign and (repulsive) Indian culture, lifestyle and population dominance. The British felt threatened and thereforeengaged in caustic negative narratives akin to racism and fear mongering. These, antis of the post-WW2 British colonial governments are well documented in the annals of history. The British had the clear intention of agitating the native people against the Indians, who were perceived as political antagonists and likely to dominate politics and be mindless to the interests of the natives.

Despite all odds, Indians progressed economically in the post-indenture Fiji, accumulated wealth and acquired a penchant for better education and jobs. Indian leaders in the colony started to agitate for more power sharing and greater economic share. This led to many confrontational political developments such as formation of worker unions and political parties. While the war since 1939 to 1945 brought its own troubles for the British, the decades from 1940s to 1970s were full of turbulence for the British colonial government in Fiji. Racism, political confrontation and political antics of the British rulers continued without respite. Most of those antics, were perceived as ploy against the rise of Indo-Fijian desire to partake in governance, the exclusive turf of the British at the time.

The most troubling development at these times for the British was the growing population of Indo-Fijians in the colony (as shown in the chart above) and the resounding demand for independence, which largely emanated from the Indian leaders of the time. This gave the British reasons to make the transition more difficult for the Indians and their leaders. The intentions of the British colonial governors to constrain the Indians in the symmetry of governance are documented in the historical accounts of the colony. The key problemsor cause of disenchantment of the British was the demand of the Indian leaders for equal value of vote and the rights to govern amid rising Indian population. The period after mid-1940s shows the period when the population of Indians exceeded that of the natives (see Chart).However, the equally important observation is the fall in the rate of population growth from mid 1960s and the decline (negative growth) of Indo-Fijian population from the late 1980s (post-1987 Coups).

The Declining Indo-Fijian Population

There were a number of reasons for the drop in the growth rate of Indo-Fijian population and the negative growth post 1987. In the 1960s to the 1980s Indo-Fijians experienced education opportunities both in Fiji and abroad and thus a slow outward mobility that started to trickle out. In this period Indo-Fijians educated their children and found ways to migrate abroad, mostly to the USA and UK and later to Australia and New Zealand. These phenomena resulted in the slowdown of Indo-Fijian population growth and the ultimate negative growth. This is visible in the slight downward tilt of the Indo-Fijian population line from 1980 onwards. The story Post-1987 is obvious. A negative growth of the Indo-Fijian population (the downward trend in the population line) clearly visible on the chart.

Even immediately after the coups of 1987 when Indo-Fijians were leaving the country in droves, negative narratives about the group continued. Indians generally were portrayed as greedy, selfish and not resembling the Fijian way of life or the Pacific cultures. These depictions generated negative broad-brushing of the Indo-Fijian community, which to some extent led to crimes and violence against them. This trend continued through the mid-1980s to early 2000 and to a lesser extent up to 2006 coup.

The 1987 coups inflicted overt violence on the community for which Major General SitiveniRabuka, former Prime Minister of Fiji is often blamed and held responsible. Discrimination against Indo-Fijians existed in the civil service,state social benefits, and targeted violence resulted in a high rate of Indo-Fijian migration. These trends are visible in the chart (the net population declined by 0.2% annually since early 1990s).

The Future of Politics and Indo-Fijians

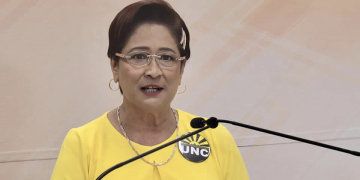

Politics is a strange game, which often leads to strange outcomes. It becomes even more strange and sometimes nasty when group rights become obsession of politicians. Fiji has passed through this over the last 50 years since independence and even prior when the British displayed their antics against the Indo-Fijians. Post-1987 coups Fiji saw many strange twists and turns, but the resolution of the 1997 Constitutionbrought a bitter end game to many participating and progressive politicians. The political parties that were involved in the amendment of the 1997 Constitution to give Fiji its progressive constitution (the 1997 Amended Constitution) lost out in the elections held under the new electoral system. Strangely, the antagonists of the amended constitution, the Fiji Labour Party won the elections and formed the government in 1999 elections, which was largely celebrated by the Indo-Fijian community. Unfortunately, a group of rebel politicians toppled the government in a coup in May 2000. This led to further, more intense violence at the time of the coup and ultimately a re-elections in 2001. During this time (5 years of government), conflict arose between the government and the Military leadership. Soon after the next election in 2006 a ‘strange’ coup happened – this time an indigenous Commander of the Military Forces toppled an indigenous Prime Minister.

This coup changed many thing and one thingmore distinctively about Fijian politics– that, the life of a government is not safe even if the Prime Minister is an indigenous person. The political event in Fiji since then has intrigued many, however, the current Prime Minister, has remained as the head of government for the last 16 years, who is largely seen as the leader of Indo-Fijians (voted by Indo-Fijians). Despite this, the government remains stable with elections due in 2022. While the current Prime Minister is indigenous Fijian, one key ministerial position is held by an Indo-Fijian and many of the bad policies by the government is now blamed (rightly or wrongly) on that Minister, who is the key Indo-Fijian Minister in the government. This could be a bad omen for political stability in future.

Incidence of Poverty among Indian Population

| Description | Population | Absolute Poverty | Poverty Rate | Distribution |

| National | 864,132 | 258,053 | 29.90% | 100.00% |

| Rural | 386,632 | 160,450 | 41.50% | 62.20% |

| Urban | 477,500 | 97,602 | 20.40% | 37.80% |

| I-Taukei (Natives) | 535,554 | 192,977 | 36.00% | 74.80% |

| Indo-Fijian | 295,326 | 58,933 | 20.00% | 22.80% |

| Others | 33,251 | 6,143 | 18.50% | 2.40% |

Source: Fiji Bureau of Statistics, 2020

How thefuture of Indo-Fijians shapes from here on is not clear but due to better access to education and the existence of diasporic Indo-Fijians in Australia, New Zealand and the US, the community feels safe and continues to progress economically. However, the rising incidence of poverty among the indigenous population (as shown in the Table) may become a source of new narrative against Indo-Fijians leading to belligerent political attitudes and propagation of racism. Therefore, a new post-COVID-19 economicorder that ensures economic empowerment and wellbeing of all citizens, may be necessary.

Note:This is a short written version of a paper that was presented at the Girmitiya Conference held via Zoom between 9th and 11th October 2021, Organised Biennially by GGI and FIAS.Also presented at a Joint Zoom meeting of ICC and AGI on the 19th of September 2021.

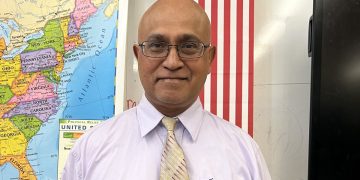

Sunil Kumar teaches development economics at the University of Fiji, Saweni, Lautoka, Fiji and Rina Kumar teaches English at the Fiji National University, Nadi Campus.