Dear Editor,

As Guyanese observe Arrival Day, in this piece I look at the experience of Indian Guyanese in Canada following the second migration of people of Indian origin.

Despite being approved as a national holiday termed Arrival Day since 2004, May 5 is truly Indian Arrival Day. East Indian immigrants were recruited in India under fixed-term contracts (indenture) and brought to Guyana (then British Guiana) to provide manual labour on the European owned sugar plantations of the colony from the time of the abolition of slavery in 1838 to 1917. The first batch arrived on May 5, 1838, and over the years, just under 240,000 were taken to Guyana. Their indenture provided for return to their homeland upon completion of their contract, however, only about 75,000 opted to return.

Starting at the bottom of the economic and social ladder, and struggling in abominable conditions, with poor wages and few, if any legal rights, the immigrants saved the sugar industry from collapse, built the rice industry, and laid a foundation for the success of their descendants. By the time British Guiana gained independence in 1966 and became known as Guyana, descendants of the Indian immigrants had made great strides socially, economically and politically.

East Indians who emigrated from India to work as indentured labourers in former British colonies constitute the first migration of Indians whose descendants then emigrated in large numbers primarily to the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, with smaller numbers to Australia and New Zealand, forming the second migration of Indians or people of Indian origin. For Indian-Guyanese, this second migration commenced in large numbers from the early 1970s to the late 1980s.

By the 1970s, Indian-Guyanese were well established as a major part of the country’s middle class in businesses and professions of law and medicine, as teachers and public servants, and as medium to large scale rice farmers. However Government’s policies started to create uneasiness, and impacted negatively on Indian-Guyanese who were supporters of the opposition party in parliament. The rice industry went into decline; Indian-Guyanese professionals in teaching and the public sector were discriminated against and marginalized; the private sector found it difficult to operate in an environment hostile to private businesses; bandits targeted Indians more and more: compulsory national service was instituted for students at the University of Guyana; and shortages of basic foodstuffs prevailed, especially items in the diet of Indians.

By the late 1970s, with the continuing deterioration in the economy, harassment and violence against political opponents of the Government, especially the leaders and members of the newly formed political party, the Working Peoples’ Alliance under the leadership of Dr Walter Rodney, other ethnicities including Afro-Guyanese also started to emigrate in large numbers. Political repression reached the level that for the very first time in history, Guyanese became eligible for refugee status in Canada. Also, a new word “backtrack” entered the vocabulary of Guyanese, in reference to the unofficial, illegal and often dangerous means and routes taken by Guyanese to reach foreign lands.

For a majority of Guyanese immigrants to Canada during this period, the decision to emigrate was not easy since they were well settled in Guyana with good, paying jobs or as owners of thriving businesses; lived in nice neighbourhoods where they owned their homes; while their children, in many cases, attended prestigious schools. Immigration, in some cases, also meant leaving parents behind, something culturally abhorrent to Indians. Worse yet, following the Middle-East oil crisis in the 1970s, Government implemented a policy of foreign exchange control that made it illegal for anyone to take money out of the country. This policy lasted until around 1991 and immigrants were allowed only around $ 20. (Can) on leaving Guyana. This meant that Guyanese were practically penniless taking up residence in Canada.

Many of the early immigrants had to adopt various strategies to survive during their first few weeks/months in Canada, seeking help from relatives, friends, former neighbours and even strangers already in Canada. In some families, parents came first and the children were left behind and to follow after their parents were financially able to support them. In other cases, a wife who was a nurse, typist, stenographer or teacher, came first as there was a demand for these professionals and the husband and children followed later. Many professionals were denied jobs for “lack of Canadian qualification” or “lack of Canadian experience” when they ventured in the job market and even individuals who had senior or administrative positions were forced to take junior positions, or jobs unrelated to their qualification/experience in Guyana. Some individuals, especially males who were head of households, found their early years in Canada daunting and humiliating.

During the 1970s when Canada faced a major economic recession, many Canadians lost their jobs, and visible minorities became victims of racial slurs and/or physical violence in certain neighbourhoods. Indian-Guyanese, termed South Asians in Canada, were called “Paki”, a derogative racial slur, and curry, a staple item of of Indian meals, incurred hostility from mainstream Canadians expressing prejudice against South Asians. However, activism by various social,religious and political organizations kept the situation under control.

Life in Canada required major adjustments for new immigrants; for instance, women who had never held a paying job before were now required to work outside the home to supplement the family’s income. This meant that husbands had to share with child care and household chores, tasks that were considered “women’s work” in Guyana. Being in the paid workforce also gave immigrant women financial independence and a stronger voice in decision making. This change in family relationships, together with apartment living, coping with the winters, and bringing up children in an environment of children’s rights and assertiveness, have not always been successfully negotiated, and in some cases have caused stress in marriages, leading to separation and divorce.

Not all Indian-Guyanese had negative experiences. Some assimilated very quickly, and a majority of Indian-Guyanese became well established in Canada which was seen as a land of opportunities, others seized the chance to advance themselves socially and financially and create fresh opportunities for their children. In the words of Indian-Guyanese-Canadian poet, Peter Jailall, “Indians are tomorrow’s people”. Indians of the first migration braved the dreaded, “kaala paani” (dark waters) to reach Guyana and lay the foundation for their descendants to reach the highest positions in the country in every field. Many of those descendants have since moved on and, now in Canada, their descendants are making their mark as scientists, professors, nurses, doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, accountants and business owners, etc.

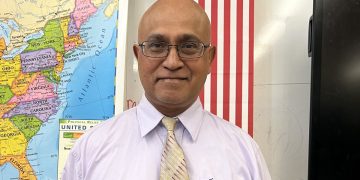

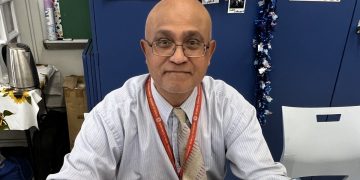

Harry Hergash