I first became interested in the National Archives in 1975 when my UG History professor Sister Noel Menezes would mention it. Sister Noel was a stickler for accurate records, and we had to pass her course on research methods before proceeding to do ‘Guyanese History 401.’ This course was really a Bachelor’s thesis that called for original research. I chose to do my research on the Amerindians, but utilized many secondary source materials, and personal interviews. In 1976, Burnham said UG students had to complete National Service in order to graduate. We finished our finals in June, and I was assigned to the National Archives for the next four months. It was a world unlike anything I had seen.

The National Archives in those days was housed in three places. The first was at the Fire Station building, in Brickdam, the second was at the Guyana Museum building, and the third was at the GPO building where most of the Immigration records were kept. I walked nervously on a rainy June morning to start my National Service at the Fire Station Building. The steps were made from old steel and had holes in them. On the first floor was the Archive. The place was dark but I managed to see long open shelves with bundles on them. Someone had forgotten to close the windows that weekend because there were puddles of water on the floor. There was no one to give instructions as to what I should do.

I unwrapped the first bundle that was completely wet. The other bundles that were next to the open windows had deteriorated to the point where the pages had become loose. Some pages were pasted together and would tear if they were not handled with care. The bundles on some of the top shelves were dry and I proceeded to untie those and put them in some order. They were rich with details about the colonial administration in Guyana. For example, the Governor of the colony would write in his own hand, to the Secretary of State for the colonies, about diseases, the need for more doctors, interior development, matters relating to expenditure, and politics. The exchanges were fascinating. It was Guyanese History 401 coming to life!

At 10am, the Archivist Tommy Payne, sauntered into the building and locked himself in his office. He emerged two hours later and I introduced myself. I explained the situation with the documents. He said, ‘you ain’t see nothing yet. But see what you gon go.’ In the second week, another student joined me and together we tried to put the documents in some order. We moved them to dry areas, labeled them, and arranged them in sequence. These documents were mostly Colonial Dispatches, Civil Lists, and Blue Books that had statements on expenditure. There were two documents that stood out.

One day, we came across a letter that was written by Governor Sir Gordon Lethem to London. He was asking for clarification on record of service for employees in the civil service. For example, if an employee worked for four years, and left, and he returned after break and worked for another ten years, would his service be continuous for pension? The feeling was since there was a break it should not be continuous, but Lethem felt otherwise, and London advised him to use his judgement. Lethem ruled that such service should be continuous, and it became known as the ‘Lethem ruling.’ I photocopied the document and gave it to the Ministry of Works and Housing that had such cases. Cabinet approved it and employees received retroactive payments and pensions.

The next document concerned Dr. Cheddi Jagan. He wrote a letter to the Governor while he was in Sibley Hall that he was willing to give his services free as a dentist, to the other prisoners. The Governor refused his request on the grounds that Cheddi would convert them to communism. One morning, I saw a chap Abu Bakr who hosted a radio program ‘Man in the Street’ on GBS. I showed him the document and asked him to mention it on the radio. Abu was nervous but he went ahead and read the letter and the refusal. In 1976, Cheddi was a nonentity in official circles and he was grateful for the mention.

Back in the Archives, there were some shelves on the top right corner that we untied and to our horror wood ants lived in them. They had bitten into the pages and important words were missing. A number of these documents dealt with the border question and some of them were beyond restoration. We found that although GPO had most of the Immigration records, they were scattered in the Fire Building as well as the Guyana Museum. We recommended that they be stored in one place. The Guyana Museum was known for old newspapers. They too were in bundles and lying around all over the place with roaches in them.

My experience at the National Archives was one of sadness. I found the place to be badly disorganized. There was no method or system to restore or preserve these priceless documents. They were dumped all over the place, moldy and neglected. They cried out for attention, but there was none. We did the best we could and wrote up long recommendations that we gave to the Archivist who promised to pass them on to the relevant people. One evening, not long afterwards, Burnham could be heard screaming into the radio, ‘a nation should be proud of its history and its heroes.’ The history was buried in dust and ants!

I spent the next two years, 1976 to 1978, in the Upper Mazaruni but did manage to visit the Archives one more time. Tommy had left and they were waiting for a permanent successor. I looked at the shelves.The wood ants were still around and yes, someone had forgotten to close the windows.

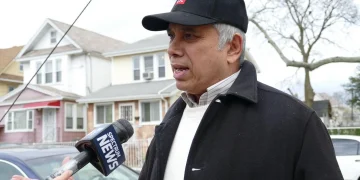

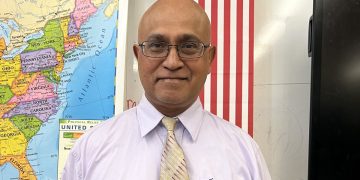

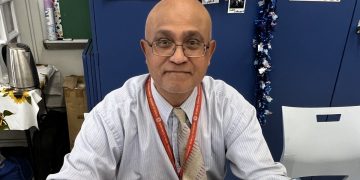

Dr Dhanpaul Narine