The Historical Crimes of the British Empire

(against India, Indo-Caribs, indentured laborers, and others)

Re: The Historical Crimes of the British Empire

It was the largest empire that has ever existed.

By 1922, the colonial power was the administering authority and power lording over a fifth of the world’s population, and for many of its subjects, the sun never rose again for them.

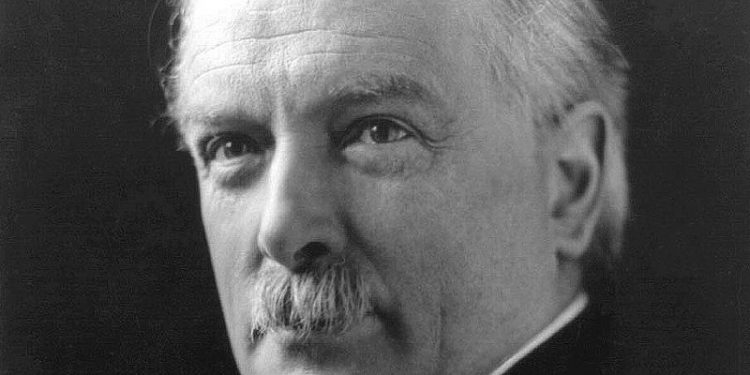

(George V was King during this time period; died in 1936; Lloyd george was the PM around this time — during the war, losing office thereafter).

For the British Empire, and as the saying goes, the sun never sets on the British Empire.

It recorded and deem policies of the British Empire and its Colonialism authority over its people around the globe and subjected them to grave and mass famines, atrocious conditions in concentration camps, and brutal massacres at the hands of imperialist troops.

The British (Brits) also played an integral role in the transatlantic and the Pacific slave trade.

The atrocities of the British Empire are well documented, and the myth of the noble colonizing power continued into recent decades.

The elements of racism against the native (aboriginal) people of Australia continue to this very day and Black Lives does matter.

The Migrated Archives

During proceedings in the British High Court in 2010, University of Warwick historian David M Anderson submitted a statement referring to 1,500 files that went missing from Kenya as British rule in the region was coming to an end.

This led the British government to concede that they had hidden or disposed of those files, and many others at a high-security facility north of London.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office was hiding around 600,000 historical documents in breach of the 1958 UK Public Records Act.

The stash included around 20,000 undisclosed files from 37 former British colonies.

Indeed, it’s common knowledge that as the British colonial edifice was disintegrating, administrators of the colonies were told to either burn their documents or try and smuggle them out.

The legal proceedings where Mr. Anderson made his revelations related to a case brought against the British government by three elderly Kenyans who claimed they’d been tortured and abused by the colonial authorities during the British occupation of their country.

The British gulag in Kenya

The British first moved into East Africa in the late 19th century, and Kenya was declared a Crown colony in 1920. In the 1940s, after half a century of British occupation, a small group of Kikuyu people – the country’s largest ethnic group – formed the Mau Mau movement and vowed to oppose colonial rule.

As word spread, Mau Mau resistance grew and they began knocking off colonial officers and local loyalists. In October 1952, Governor Evelyn Baring declared a state of emergency, which was held until 1960.

In 1964, the colonial army began erecting a network of concentration camps. Historians estimate that 150,000 to 1.5 million Kikuyu people were detained. Conditions within the camps were atrocious, and people were systematically beaten and sexually assaulted during questioning.

The grandfather of Barack Obama, Hussein Onyango Obama suffered severe mistreatment in the camp where he was held, which included having pins forced under his fingernails.

The British government, after being continually defeated in the High Court, agreed to settle the Mau Mau case in 2013.

On June 6 that year, then UK foreign secretary William Hague announced 5,000 survivors would each receive £3,800 payment, and he also expressed the nation’s sincere regrets to Kenyans who were subjected to “torture and other forms of ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration.”

The desecration in India

It was said that India was the jewel in the crown of the British Empire.

The British East India Company began making avenues into the subcontinent in the 17th century, and India was established as a Crown colony in 1858. The British Raj systematically transferred the wealth of the region into their own coffers. In the northeastern region of Bengal, “the first great deindustrialization of the modern world” occurred.

The prosperous two-centuries-old weaving industry was shut down after the British flooded the local market with cheap fabric from northern England. India still grew cotton, but the Bengali population no longer spun it, and the weavers became beggars. India suffered around a dozen major famines under British rule, with an estimated 12 to 29 million Indians starving to death.

Some of the worst British Empire famines subjected and projected in India: 800,000 died in the northwest Provinces, Punjab, and Rajasthan in 1837–1838; perhaps 2 million in the same region in 1860–1861; nearly 1 million in different areas in 1866–67; 4.3 million in widely spread areas in 1876–1878, an additional 1.2 million in the northwest Provinces and Kashmir in 1877–1878; and, worst of all, over 5 million in a famine that affected a large population of India in 1896–1897. In 1899–1900 more than 1 million were thought to have died and about 5 million during world war. Large parts of India were affected and millions died.

Florence Nightingale pointed out that the famines in British India were not caused by the lack of food in a particular geographical area. They were instead caused by inadequate transportation of food, which in turn was caused due to the absence of a political and social structure.

Nightingale identified two types of famine: a grain famine and a “money famine”. Money was drained from the peasant to the landlord, making it impossible for the peasant to procure food.

Money that should have been made available to the producers of food via public works projects and jobs was instead diverted to other uses. Nightingale pointed out that money needed to combat famine was being diverted towards activities like paying for the British military effort in Afghanistan in 1878–80.

Economy Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen found that the famines in the British era were not due to a lack of food but due to the inequalities in the distribution of food. He links the inequality to the undemocratic nature of the British Empire.

Mike Davis regarded the famines of the 1870s and 1890s as ‘Late Victorian Holocausts’ in which the effects of widespread weather-induced crop failures were greatly aggravated by the negligent response of the British administration.

This negative image of British rule is common in India. Davis further argues that “Millions died, not outside the ‘modern world system’, but in the very process of being forcibly incorporated into its economic and political structures. They died in the golden age of Liberal Capitalism; indeed, many were murdered … by the theological application of the sacred principles of Smith, Bentham and Mill.”

However, since the British Raj was authoritarian and undemocratic, these famines only occurred under a system of economic liberalism, not social liberalism.

Tirthankar Roy suggests that the famines were due to environmental factors and inherent in India’s ecology. Roy further argues that massive investments in agriculture were required to break India’s stagnation, however, these were not forthcoming owing to the scarcity of water, poor quality of soil and livestock and a poorly developed input market which guaranteed that investments in agriculture were extremely risky.

After 1947, India focused on institutional reforms to agriculture however even this failed to break the pattern of stagnation. It wasn’t until the 1970s when there was massive public investment in agriculture that India became free of famine, although Roy is of the opinion that improvements in the market efficiency did contribute to the alleviation of weather-induced famines after 1900, an exception to which is the Bengal famine of 1943.

Evidence suggests that there may have been large famines in south India every forty years in pre-colonial India and that the frequency might have been higher after the 12th century.

These famines still did not approach the incidence of famines of the 18th and 19th centuries under British rule.

Although it’s impossible to compare accurately as there are no accurate records before the British arrived.

The Orissa famine occurred in northeastern India in 1866. Over one million – or one in three local people – perished. As the region’s textile industry was destroyed, more people were pushed into agriculture and were dependent on the monsoon.

That year, the monsoon was weak. Crops didn’t grow and many starved to death.

The colonial administration didn’t intervene as the popular economic theory of the time reasoned that the market would restore proper balance, and the famine was nature’s way of responding to overpopulation.

When the British finally got out of India, they simply drew a line down the map and partitioned the subcontinent into India and Pakistan.

The move led to the mass migration of around 10 million people, and when it escalated into sectarian violence an estimated one million lost their lives.

A southern invasion

The British began invading Australia in 1788, under the pretext that it was Terra Nullius: a land with no owners.

The High Court of Australia abolished the legal fiction of terra nullius in its 1992 Mabo versus Queensland (No 2) ruling.

It was a landmark decision, but not everyone was surprised that the court found that there were actually sovereign people living on the land prior to the arrival of the British. At that time, there were an estimated 750,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living across the continent.

The First Fleet arrived in the vicinity of what is now the city of Sydney in 1788. Around 15 months later, at least 50 percent of the local Aboriginal population was dying due to a smallpox epidemic.

Some historians put the outbreak down to contact with the Macassans from Sulawesi in the far north of the continent.

However, others argue that bottles of smallpox were brought across on First Fleet ships, and the disease was then released, either accidentally or with clear intent.

Dozens of massacres of Indigenous people were carried out by the British right up until the 1920s. On June 10, 1838, the Myall Creek massacre occurred near Inverell in NSW. This tragedy is well-known as it was the first time Europeans were brought to justice for such an atrocity in Australia.

At the time about 50 Aboriginal men were working for stockmen in the area. One evening the stockmen rode into the local people’s camp, tied up 29 men, women, and children, and beheaded them. Seven of the perpetrators were eventually brought to trial and hanged.

Today, in Australia, the colonial legacy continues.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are the most incarcerated population on earth.

As of March this year, there were 11,288 Indigenous adults detained in the Australian prison system.

First Nations peoples account for only 2.5 percent of the overall Australian adult population, yet they represent 28 percent of the adult prisoner population.

A Case of Doctrine of Terra Nullius verse the Doctrine of Reception in Fiji

Before Fiji was ceded to Great Britain, evidence suggests that it was the Australians and Australian enterprises who had the desire and want of taking prime and productive agricultural land in Fiji.

Two of Fiji’s first constitution was drafted in Victoria and were systemically adopted in Fiji before Ratu Seru Cakabau was accepted, recognized, and officially promoted to be the King of Fiji.

Over 40,000 native Fijians were systematically introduced to smallpox and other diseases by the Australians as those native Fijians were either deemed unproductive towards agriculture or were a threat to the establishment of the new British Colony of Fiji.

Although evidence suggests that Ratu Seru Cakabau traveled to Sydney, Australia with his son, in 1872 and upon his return, over 40,000 native Fijians were killed by the act of genocide and the introduction of white men’s disease.

Fiji was ceded to Great Britain in 1874, when cannibalism and tribal wars were evident and at the same time, Fiji was the largest producer of cotton before the markets crashed.

By 1878, Fiji had 12 independent sugar mills and over 800 planters of sugar cane whose products were being exported to Australia.

By 1879, Indentured Indians who were also British subjects were introduced to Fiji to work in agriculture including sugar, cotton, and copra plantations.

The forceful relocation and system recruitment of a population against their will, with false and misleading promises, are all acts of genocide and atrocity crimes against humanity.

A bloody trail

These are only some of the crimes perpetrated by the British Empire as they carried the greatest land grab the world has ever seen either through the Doctrine of Discovery; the Doctrine of Reception or the Doctrine of Terra Nullius.

There were concentration camps in South Africa, where tens of thousands of the Boer population were detained in the first years of the 20th century.

The Irish potato famine occurred in the 1840s, leading to the deaths of well over a million people.

There were torture centers in Aden in the 1960s, where nationalists were kept naked in refrigerated cells.

When the Empire was facing communist insurgents during the Malaya Emergency of the 1950s, they simply decided to imprison the entire peasant population in detention camps. And the list goes on…

But the crimes of the Nazi’s are more serious than the crimes of the British Empire and its 4 cousins, namely Australia, New Zealand, the United States of America, and Canada.

The implied law and the application of the British Law give justice to the millions that have been murdered, systemically killed by the acts of the British Empire and it’s four cousins.

Is there any form of justice available for the crimes of the British Empire and its four cousins?

Regards,

R Krishna Raju (Mr.)

PhD Candidature (Law) by Research

(Editor’s Note: Mr. Sunil Kumar penned in response: Thank you for this information. It would be great if a Zoom seminar can be organised for people to know these atrocities of the British. Girmitiyas around the world are not much familiar with these issues for which a lot of them see the British as benign occupiers of India, save the Jallianwala Barg and a few other incidents).