Article By Tarun Basu Nov 10, 2023

(The writer is a veteran editor, founder, South Asia Monitor and editor-author of “Kamala Harris and the Rise of the Indian Americans”).

Ironically, the forced migration of indentured laborers or girmityas also laid the seeds of a diaspora in countries where Indians of another generation looking for better economic opportunities would not have normally settled.

Indentured route

The Indian diaspora – estimated at 30 million and growing depending on how inclusive one makes it – has been the subject of much writing and discussion in recent times. It is seen as an important source of ‘soft power’ for India, and the one to leverage it politically and diplomatically has been none other than Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who unfailingly includes an engagement with the diaspora in every country he visits where Indians have settled in substantial numbers. The Indian diaspora is a source of investment and support for the ruling dispensation, and large sections of the diaspora in turn idolizes Modi – he calls them “brand ambassadors” of the country – and the mass adulation that he receives from New York to Sydney has been the envy of his hosts, whether in the United States to Australia.

However, the diaspora is not just the affluent and well-settled Indians In the richer economies of the United States, United Kingdom, Europe, or Down Under who have been the subject of special reports in The Economist and other reputed international publications as a “powerful resource” for the nation. When talking or writing about the Indian diaspora and their experiences, a segment that is often lost sight of are the so-called ‘lost Indians’ – descendants of “more than 2,2 million indentured labour (who) were moved from India to more than 26 countries in various parts of the world, making it one greatest mass movements of India’s future Diaspora worldwide”.

Bhaswati Mukherjee, a former Indian diplomat who was Ambassador to UNESCO and the Netherlands and has studied this subject extensively, delves in her recently published book “The Indentured Route: A Relentless Quest for Identity”, about how a few million Indians were shipped in the 19th and early 20th century as indentured or contract labour to work in British plantations across the world, from Suriname to South Africa, to Mauritius and the Reunion Islands; to Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean.

The Kalapani metaphor

This is a story that hasn’t been told in its entirety or the trials and tribulations of the shipped labour documented for posterity. “The journey of India’s children across the Kalapani, their suffering and humiliation at the hands of the colonizers and their relentless quest for identity cannot remain an untold narrative,” argues Mukherjee who chose to shine the light on what she calls “a forgotten part of our history” in which the British, adept at using transportation to distant shores as a form of punishment, came up with the system of indenture “as a substitute for slavery” after the British Parliament abolished slavery in 1833.

How the term Kalapani – literally meaning ‘dark waters’ – gained currency as a metaphor for the forbidding ocean whose crossing, it was believed, would not just bring them evil but make high-caste Indians lose their exalted status is itself a fascinating commentary on how the British played upon Indian religious sentiments and economic deprivation, which in many ways was their creation, to set one community against another in the process of crushing “a so-called subordinate culture”.

The penal act of transportation across the high seas and oceans as contract labour to run the sugar and coffee plantations of British, as well as Dutch and French colonies, that had lost African labour following the abolition of slavery was just not an act of crafty business and political manipulation but a cynical economic action that duped tens of thousands of poor Indian workers into believing that they were being given the choice of a better life which they could harness to better the indigent family conditions back home.

This thinking gets reinforced by a question from the Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series quoted by Mukherjee that, in a bout of self-searching, wonders if “It is important to consider whether the Indian indentured labour had been inveigled into a new system of slavery’.

Rainbow nations

Ironically, the forced migration also laid the seeds of a diaspora in countries where Indians of another generation looking for better economic opportunities would not have normally settled. “The movement of one-and-a-half million Indians across continents from the mid-nineteenth century was dictated by the demands of imperialism and finance capitalism,” noted Mukherjee, as the “descendants of the indentured built new rainbow nations in the erstwhile plantation colonies as free and independent states” to become the “protagonists of a hybrid culture, similar to India but also different.”

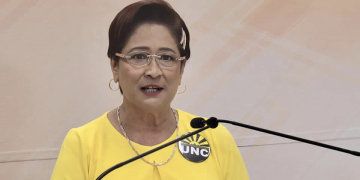

How Indian culture and traditions, in the form of festivals like Diwali, have not only taken roots in these countries, much to perhaps British chagrin, in the form of cross-cultural celebrations is perhaps illustrated in the nine-day Divali Nagar festival, a popular diaspora draw, that takes place in Trinidad and Tobago, where nearly 40 per cent of the 1.3 population of the twin islands is of Indian extraction.

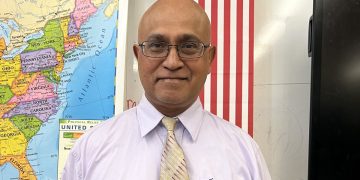

At the recent inauguration of the 35th edition of the festival, Mayor Faaiq Mohammed of Chaguanas, Central Trinidad, pointed out that the National Council of Indian Culture, through the Divali Nagar festival, “(had) brought cultural traditions of our ancestors, allowing our multi-cultural and multi-religious and multi-ethnic society to embrace Divali and what it represents as a national festival” in the Caribbean nation.

This is a meticulously researched book spanning continents that narrates the painful story of India’s earliest migrants who established new cultural roots that kept them emotionally connected to their native land and whose forefathers’ epic transoceanic journeys have now come to be acknowledged in the UN system as one of history’s greatest tragedies of human exploitation just as slavery had come to be accepted.