It might surprise readers that Prof. Clem Seecharan viewed Bachu’s writings as “partisan”. I reproduce ( in my book A Mauling of Indians, where I rebut his arguments) the following excerpts from his Moray house speech in 2014 (See link below) which triggered my book:

Seecharan’s ‘revised’ Indentured Indian story and history

An extensive excerpt of Prof Seecharan’s claims is provided so the reader could appreciate how the Indentured Indian story, history and legacy has been ‘revised’ by this acclaimed Guyanese historian to suit a Caribbean academic and lay readership – which Dr. Ramharak has concerns about over their “resistance to this Indo-centric approach”. Seecharan states:

“I was in my early thirties before I discovered that they [indentured Indian labourers] came primarily from the most impoverished part of India, virtually lawless, feudal in its social organisation and ossified by the immutability of caste prejudice. It was a stultifying environment where thuggery was commonplace. The heavy hand of the high caste landlord/money-lender aided by his goons, as I discovered a few years ago on a visit to eastern UP, has lost none of its ancient aptitude for brutal summary enforcement. (It is noteworthy that both words, “thugs‟ and “goons‟, are of Hindi derivation). Even Brahmins could become impoverished, indebted to landlords and money-lenders; besides there were many personal, domestic reasons why some – both men and women – would have wanted to flee [India]. (Italics added).’

“It is generally not known, but significant, that about two-thirds of the female indentured labourers went to Caribbean plantations on their own, unaccompanied by any relatives; 82% were aged between 10 and 30. Even more indentured men declared themselves as “single‟. There was a lot to hide.

“Amnesia and fantasy are at the fount of the construction of Indo-Guyanese identity. This was an imperative of self-preservation and the regeneration of self in the new land. Individually and collectively, not to forget the agonising reality of lives in India, blighted by famines and the loss of child-wives and child-husbands; child-wives and young widows “marooned in pitiable existence” in the homes of oppressive in-laws – a shame to return to parent’s homes – thus a “plague on both houses”; “rudderless” having been deserted by husbands who had escaped, internally or overseas, to greener pastures; consequent “infidelity‟ actuated by chronic poverty and sexual deprivation; the placelessness of widows in Hindu society – indeed, the “immemorial poverty‟ (Naipaul) of eastern Uttar Pradesh and western Bihar – was to self-destruct. Hardly any had the mental resources to accommodate such a past with a measure of equanimity; it is unconscionable to expect them to. It had to be erased by silence, but because they were all in the same boat, women and men, it was easier to navigate away from the quicksand of that unimaginably painful reality. They knew where to draw the line, not to burden each other to unmask the dark private recesses. They kept that past submerged: nothing would detach them from their cultivated amnesia. They had come to believe their silent reworking of the truth – and so have their descendants [Indo-Guyanese].

“They could absolve themselves of any responsibility for their flight, attributing total agency to the infamous arkati, the legendary, shadowy anti-hero, an unexamined folk figure of unmitigable infamy, who supposedly duped all into “a new slavery‟ and lured women in particular into a veritable narak (hell) – a constructed universe of moral depravity, rampant debauchery and unexampled degradation, on the plantations of the sugar colonies. This was not only, by and large, a distortion of conditions under indentureship; it was an ironic narrative, redolent of a displacement tactic, more reflective of eastern UP and western Bihar, whence they had fled.

“We [Indo-Guyanese] continued to wallow in the old tales of deception, kidnapping and ‘a new slavery’… they have become an armour of Indo-Guyanese identity – the badge of suffering to rival African enslavement

“Even Bechu’s fearlessly ‘partisan’ writings, in the late 1890s, on behalf of his fellow ‘bound coolies’ (which I discovered in the mid-1990s), had not sought to remedy this, although there were many thousands in British Guiana. Agency was denied the indentured labourers.

“Although Prof. Lal acknowledges that while a strand [a straw, a veritable modicum, an iota, a crumb…] of deception permeated recruitment in India, he does not see indentured women as “helpless victims” mere “pawns in the hands of unscrupulous recruiters”. He considers them “actors in their own right”; he gives agency to these women. They were mostly very young…”

Translating the latter, this author arrives at: By the Indo-Guyanese continuing to “wallow in the old tales of deception, kidnapping and ‘a new slavery’” we are denying that the indentured labourers, including “very young” girls, only ten (10) years old, made the free choice – as “actors in their own right” – to flee Mother India!

At this stage, even though recruitment will be dealt with later, Seecharan’s assertion about ‘ten year old girls” is so patently absurd that a passing comment is warranted. He wants us to believe that the young Indian women and girls – as young as ten (10) years old – were “actors in their own right” – as he puts it in another place, in a rigid “Brahminical” environment which was inimical to women! Where and how would these likely undereducated, hapless “mostly very young” women (veritable children) develop this independence of mind and courage to take flight on sailing ships, which they would have never seen, to an unknown land – several months’ journey away? These considerations go unheeded by Prof. Seecharan.

And, here is my response (p37):

Bechu partisan?

It is significant that Prof Seecharan now (via his “revisionist” perspective) refers to the literate indentured labourer, Mr. Bechu’s, letters to the press – in which he exposed the harsh and unjust treatment meted out to “his fellow ‘bound coolies’” – as “partisan” and that he ‘failed to remedy the “constructed” tales of deception, kidnapping and “a new slavery” or in Seecharan’s words: “a distortion of conditions under indentureship”.

I expect other informed historians on colonial indentureship to the West Indies, perhaps even the wider Caribbean, would be dismayed and nonplussed leading then to take issue with this characterization that Bechu was not providing a true, objective (non-“partisan”) account of the recruitment in India and the treatment of Indian labourers on the plantations. Ironically, Prof. Baytoram Ramharak wrote in the Introductory Essay to the Centenary Celebration of the Arrival of Indians to British Guiana (1838-1938):

Professor Clem Seecharan’s Bechu, “Bound Coolie” Radical in British Guiana, 1894-1901 reproduces the letters from the Daily Chronicle of an extraordinary Indian labourer who challenged the plantation system in British Guiana and exposed the evils of Indian indentureship…The numerous letters of this unsung Indian hero, and their significance in the struggle against the indenture system were brought to the public’s attention from the annals of history and carefully analyzed in this 1999 study” (p5).

Perhaps because of Prof. Seecharan’ prior confidence in Mr. Bechu, Dr. Ramharak is clearly impressed with Mr. Bechu’s championing the indentured labourers’ condition under the plantation system:

…Mr. Bechu, the radical Bengali champion of Indian indentured workers whose prolific and astutely written letters to the press exposed the injustices and immorality of the British treatment of Indians (p7).

Furthermore, Dr Ramharak is critical of those scholars who adopt the Euro-centric approach writing: “…examining that [Indian] experience from a European perspective contribute[s] to the underdevelopment of a legitimate and credible Indian historiography”. The said Eurocentric perspective permeates Seecharan’s narratives as is being revealed herein.

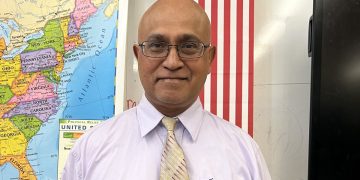

By Veda Mohabir