Dear Editor,

I write regarding the article ‘Rethinking Forbes Burnham: Revelations from the “303 Committee” on laying the foundation for Guyana’s dictatorship’ by Baytoram Ramharack (Stabroek News, November 14, 2021). In the article, Dr Ramharack states “Following the August 1961 elections, the Americans were still prepared to hitch their wagon with Jagan, but they were optimistically cautious…”. In my view the US Declassified documents do not support this position. Instead, an objective look at all the documents would indicate that Jagan’s fate was sealed on May 5, 1961 (i.e. more than three months before the elections) when the National Security Council (NSC) became involved with the task “to forestall a communist take over” in then British Guiana.

President Kennedy took office on January 20, 1961. In April, he approved a covert operation, termed the Bay of Pigs invasion, against Fidel Castro’s Cuba. The operation failed, causing him and the CIA major embarrassment. Consequently, his administration was not prepared to allow the emergence of “another Cuba” in the hemisphere. Jagan’s win in August 1961 was simply a temporary setback for the US. The documents show a persistent attempt by his administration from April 1961 until the elections of August 21, 1961 to prevent Jagan from coming to power.

The record shows that the President had briefly discussed the Guyana situation with the British Prime Minister in April and “The Department of State has been actively working with the British on this question for some weeks.” An internal August 5, 1961 memo notes “British have not been willing to undertake any operation or permit us undertake operation to prevent Jagan victory and generally take view that Jagan is probably ‘salvagable’.” Another August 5, 1961 memo, this one from the US to the UK states “… we are not inclined to give people like Jagan the same benefit of the doubt which was given two or three years ago to Castro himself”. The UK responded on August 18 stating “Your people and ours have looked very carefully into the possibilities of taking action to influence the results of the election… I am convinced that there is nothing practical-i.e., safe and effective that we could do in this regard… In any case, there would not now be enough time at our disposal”.

Further, Dr Ramharack writes “A more sympathetic Arthur Schlesinger, Kennedy’s Special Assistant, in his memo to Kennedy on August 30, 1961 attempted to “salvage Jagan” by offering Jagan technical and economic support, assistance with Guyana’s admittance into the OAS and Alliance for Progress, and “a friendly reception” with Kennedy during his October meeting. However, after assessing Jagan’s plans for the economic and political development of a future Guyana on October 25, 1961 following his meeting with President Kennedy, the US-Jagan relationship quickly deteriorated.”

In the above paragraph, Ramharack omits mention of the August 18 memo from UK’s Lord Home which suggested the idea of aid to Jagan. Also, he ignores an August 26, 1961 memo from the Department of State conveying a note to Lord Home. This note is critical as it became the basis of the US policy after Jagan’s victory. It proposed accepting Lord Home’s suggestion of aid (to appease the UK) while gaining their support to initiate a covert plan, as can be deduced from this excerpt:

“In your letter of August 18 you mentioned that our support for your policy would be of great help. If agreeable to you, I suggest that representatives of our two governments again sit down to discuss the situation. They might start with a review of the intelligence assessment, then go on to consider courses of action in the political, economic and information fields. I also attach importance to the covert side and recall that in June Hugh Fraser told David Bruce you would have another look at what could be done in this field after the election…we might try to commence the discussions the week of September 4.”

Schlesinger’s memo of August 30, 1961 (referenced by Ramharack) of aid to Jagan is in fact based on Lord Home’s memo of August 18 which paved the way to gain UK support in order to initiate planning for covert action. Also, Dr Ramharack seems to rely on Schlesinger’s book, A Thousand Days (published in 1965) for background historical information on the Jagan-Kennedy meeting of October 25 and subsequent development. However, Schlesinger was not an independent observer. He too supported the removal of Jagan, as can be seen in his memo to the President of June 21, 1962 after his return from a three-day trip to British Guiana “All alternatives in British Guiana are terrible; but I have little doubt that an independent British Guiana under Burnham (if Burnham will commit himself to a multi-racial policy) would cause us many fewer problems than an independent British Guiana under Jagan”. Decades later Schlesinger admitted that his book did not tell the full story regarding the meeting.

Like others, Dr Ramharack has hung his hat on Jagan’s answer to Lionel Luckhoo at the 1962 Wynn Parry Commission hearing. He writes “On June 22, 1962, during cross-examination by the Commonwealth Commission of Inquiry into the January riots, Jagan bared his communist credentials for the world to see”. Ramharack ignores the badgering of Jagan to elicit that answer. The perspective of Sir Ralph Grey, then British Governor, is worthy of note. In a letter to the Colonial Office on July 3, 1962, regarding a dinner-party he hosted for a visiting US State Department Official for Caribbean Affairs, he wrote “…Lionel Luckhoo was there and I purposely teased him a little about his cross-examination of Jagan before the Commission and said that while it might have been a forensic triumph it did not seem to have any particular purpose, that it had wrung out of Jagan admissions that would be widely publicized in their simple form but that were in fact much hedged about with qualifications, etc., and that this would do the country no good abroad…”

In any case, Jagan’s admission of being a communist was irrelevant in the scheme of things. His admission came on June 26, i.e. three months after the US Secretary of State had already written on February 19, 1962 to his British counterpart “I must tell you now that I have reached the conclusion that it is not possible for us to put up with an independent British Guiana under Jagan”. Interesting too is the fact that on February 27, 1962 Iain Macleod (Secretary of State for the Colonies, October 14,1959 – October 9, 1961) told Schlesinger in a meeting with him that “Jagan is not a Communist. He is a naive, London School of Economics Marxist filled with charm, personal honesty and juvenile nationalism; The tax problem which caused the trouble (strike against the 1962 budget) in Feb was not a Marxist program; Jagan is infinitely preferable to Burnham; If I had to make the choice between Jagan and Burnham as head of my country I would choose Jagan any day of the week.”

In later years, according to an article by Victor Navasky (https://www.thenation.com/article/schlesinger-nation/) Schlesinger apologized to Jagan for “a great injustice” he and his Kennedy colleagues had helped to perpetrate. Also, eminent British journalist Tim Reiner in a 1994 article (https://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/30/world/a-kennedy-cia-plot-returns-to-haunt-clinton.html) notes that

Schlesinger “acknowledges” that his account of the Kennedy-Jagan meeting of 1961 as documented in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, A Thousand Days, “is incomplete”. He further quotes Schlesinger as saying “The British thought we were overreacting and indeed we were. The CIA decided this was some great menace, and they got the bit between their teeth. But even if British Guiana had gone communist, it’s hard to see how it would be a threat… The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it”. It is now long overdue for Guyanese academics like Dr Ramharack to heed Schlesinger’s advice and rewrite the history.

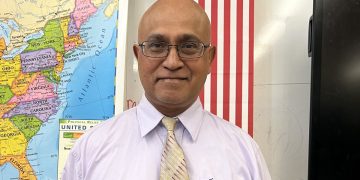

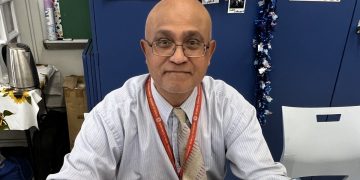

Yours faithfully,

Harry Hergash, Writer of Books on Indian Guyanese