As I continue my commentary on the Indo-Trinidadian presence in TnT today, I would have ruffled some feathers by my statements and would have evoked a negative reaction in other quarters. This is to be expected as many people in this country refuse to come to terms with the truth. They are content with harbouring long-held prejudices, facile perceptions of Indo-Trini opulence and a blinkered perspective on ethnic status and well-being. However, I deem it my duty to continue to elucidate reality for those with an open mind.

The misconceived view that Indo-Trinidadians possess the largest proportion of the wealth of the country through their alleged dominant stake in the economy has had a long history. It is a notion repeatedly expressed in the media, in social circles and even in the corridors of Parliament. I am not sure how this view of Indo-Trinidadian dominance of business and wealth gained traction- whether it was due to the visibility of numerous small to medium retail outlets owned by Indos or whether it was the reputed widespread ownership of land or whether their stake in the economy as a group was greater than that of Afro-Trinidadians.

The proposition of dominance however did not accord with the reality I perceived as regards the presence of Indo-Trinis in the economy. I therefore decided to examine the veracity of this firmly held conviction which I assumed to mean that Indo-Trinidadians owned the major percentage of the economic assets of the country taking all sectors of the national economy into account.

In the late 80s, I looked at the major sectors of the economy according to GDP categories and assumed that the value of assets employed in them would be reflected in their respective contributions to the GDP. I then proceeded to a rudimentary analysis of the ownership of these assets. I published my findings in a series of columns in the Trinidad Express in 1990 and compiled them in a collection titled “The Political Uses of Myth” to which reference can be made. In 1987, the sectoral breakdown of the GDP was as follows:- the oil industry 26.2 per cent; government 16 per cent; transport, storage and communications- 10.3 per cent; finance, insurance and real estate- 9.8 per cent; construction and quarrying- 9.7 per cent; manufacturing- 8.2 per cent; distribution and restaurants- 8.2 per cent (inclusive of wholesale and retail trade) and agriculture-4.0 per cent.

On examination of the ownership of assets in these categories it was found that the State and foreign companies virtually monopolized asset holdings in the dominant oil industry and the State also had a significant presence in other sectors including transport and communications, finance, construction and manufacturing. While Indo-Trinidadians had a presence at the ownership level in road transport (not air or sea transport), the smaller insurance companies, civil construction and small scale manufacturing, there was absolutely no question of dominance in these areas. It was only in the Retail Trade which accounted for about 5 per cent of the economy and in agriculture 4 per cent and rural real estate possibly 3 per cent, one can speak of significant Indo-Trinidadian asset holdings. It is therefore a figment of the imagination to speak of Indo-Trinidadian dominance of the economy. Even if we exclude the ownership of assets held by the State (which are under the control, management and disposition of Afro-Trinidadians) no such overwhelming ownership by Indos in the remainder of the economy is discernible.

Fast forward to 2019, and, though the classification of the activities in the various sectors was subject to some change, the profile of asset ownership continued to reflect a moderate Indo-Trini presence in many sectors. “Mining and quarrying”, now incorporating the extractive element of the oil and gas industry, accounted for 12.9 per cent of GDP. The item “Manufacturing” which now included oil refinery and petro-chemical operations, accounted for 18.6 per cent. Of this total, manufacture of food, beverage and household items in which Indo-Trinis would have had a notable presence, would probably account for about 6 per cent of the total in this category. It should be noted that local conglomerates (non Indo-Trinidadian entities) such as Massy Holdings and CL Financial had a significant presence in petrochemical manufacture while ANSA McAl advanced to greater prominence in manufacturing and financial services. “Government” (Administrative Support, Public Administration and Defence, Education, Human Health etc.) remained comparatively constant at 15.5 per cent.

Notable changes in the GDP took place in some sectors. Agriculture, in which Indo-Trinis were prominent, was now reduced to 1 per cent of GDP; transport and storage to 3.7 per cent and construction to 5.6 per cent. However, by far the most outstanding change was the huge increase in wholesale and retail trade inclusive of vehicle repair from 8.2 per cent to 21.1 per cent. This increase no doubt reflected the plethora of large malls and distribution and food franchise outlets constructed over the last decade or two which are under the ownership of ethnic groups other than Indo-Trinis.

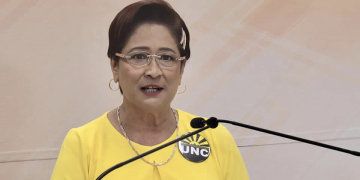

Space does not permit me further elaboration but, given the evidence thus far adduced, there is absolutely no justification for the continuing assertion that Indo-Trinis dominate ownership of economic assets at the overall national level. The myth, however, persists. Only recently the leader of an obscure political party would posit that “The grandchildren of India ….went on to become the largest and wealthiest subgroup in the country”, a statement no doubt intended to mamaguay Indo-Trinis. As John F. Kennedy noted, “Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.”

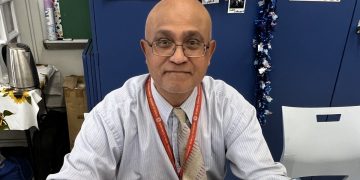

By Trevor Sudama