By Jean-Claude Escalante

This is the final instalment in my Spotlight on Indian Leadership series. Last week, we looked at the legacy of Bhadase Sagan Maraj. In this article, we will look at perhaps the most important legislator in our post-independence history— Rudranath Capildeo.

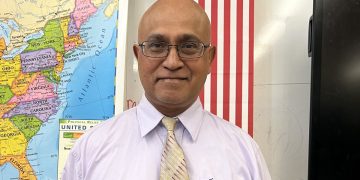

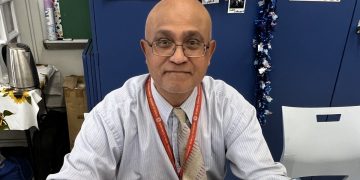

After Bhadase fell ill in 1959, leadership of the Democratic Labour Party was conferred on Rudranath Capildeo. He was a natural rival to Eric Williams having possessed a PhD in Mathematical Physics from the University of London. Capildeo also authored a Mathematics textbook. Whereas Bhadase was often mocked for his lack of formal education, Williams could not make such remarks about Capildeo.

The 1961 election is one of the most controversial elections in our history and is noted for being alarmingly violent. There were three major issues heading into the election that year: (1) the introduction of voter registration and identification cards; (2) the demarcation of electoral boundaries; (3) the introduction of voting machines.

It was argued that the voter registration process was designed to confuse the illiterate Indian population who could not understand the complex application process. The PNM was also accused of gerrymandering. To the north of Port of Spain, for instance, where the PNM had lost two consecutive elections, a part of Belmont, where they won, was added to the boundary. The DLP requested radio time to explain its position on the voting machines but they were denied the use of the state-owned radio station—the only radio station at the time.

DLP meetings were constantly interrupted by hecklers and it was virtually impossible for them to get a hearing in PNM strongholds. At one PNM meeting, Vice-President and Government Minister, Isabella Teseha, remarked that it was a “good sign” for the people of the area that “few, if any, DLP faces” could have been found in the crowd—referring of course to the Indians that were in attendance.

One month before the election, a group of PNM supporters raided a gas station, looted shops and threw stones at a DLP office as well as candidates. The DLP was forced to abandon all campaigning activities three weeks before the election because of this. Having reached his breaking point, Capildeo called the Indian population to arms. A State of Emergency was declared and the police raided the homes of several Indian communities in search of guns though none were found.

Needless to say, the DLP lost the election. But the fighting spirit of Capildeo raged on at the Independence Conference the following year. The PNM showed complete disregard for the DLP by drafting the Independence constitution without any consultation from the Opposition. The powers granted to the Prime Minister under this constitution would have made him the sole governing authority. Members of the Boundaries Commission, the Public Service Commission as well as the Judicial and Legal Service, were all to be appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister.

Capildeo secured some major concessions at the conference. These included independence of Judiciary, consultation between the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader on matters of national concern, and the right of appeal to the Privy Council—the latter of which became instrumental in later years in the fight against discrimination against Indo-Trinidadians.

In 2002, without expressing any reason, the Maha Sabha’s application for a radio licence was rejected by the government. Yet the government awarded an overnight licence to Louis Lee Singh. After attempts to secure a licence proved futile in the local courts, the Maha Sabha took the matter to the Privy Council where they emerged victorious in 2006. But even then, the government showed blatant disrespect for the judgment and refused to grant the Maha Sabha a licence—though they eventually complied.

By the 1970s, Capildeo played a less active role in politics due to his commitments abroad and became a less effective legislator. By 1971, in-fighting in the DLP tore the party apart and by 1976 the United Labour Front, led by Basdeo Panday, came to represent the voice of the Indian population.

It is indeed unfortunate that Capildeo’s track-record was tarnished by his short fuse and questionable allegiances. But where would Trinidad be today if not Rudranath Capildeo? It’s a scary thought but one that can only occur to those who are familiar with the history. Our constitutional rights are taken for granted today and nowhere is this more demonstrable than the movement towards the Caribbean Court of Justice or any time the words “Maha Sabha” and “Privy Council” appear together in the media headlines—much to the ire of the population. Freedom is a privilege and those who did not fight for it cannot possibly appreciate it as much as those who died for it.