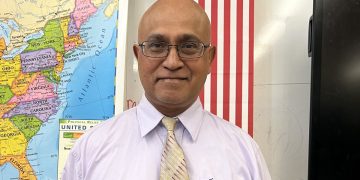

From Gokarran Sukhdeo

INTRODUCTION

This is a two-part non-fiction story. (I use the word, ‘non-fiction’ because several facts stated are going to be unbelievable; and the word, ‘story’ instead of ‘paper’ because I would like the reading to be less academically dry-as-dust, and more empathetically human.) It is a neo-Marxian analysis because it puts people at the center of its universe, not capital. It deals with the human aspect of sugar, its failure, causes of its failure, and the prospects of turning around that failure to launch a diversified agriculture revolution in Guyana, aided by the country’s enormous oil and gas windfall. This revolution will begin at Wales where massive infrastructural developments are currently on-going. It is ironic that Wales sugar estate, unjustly and abruptly closed, its thousands of starving citizenry thrown to the wolves, will rise like a Cinderella (now, the word ‘story’ is beginning to sound better) and become the Dubai or more appropriate, the Oman of the West.

Having arrested your attention, I hope you follow me intricately as our story deconstructs the historical and theoretical-political nature of sugar in Guyana, examines its current insolvent situation which appears unsalvageable, and charts a course for Guysuco and agriculture in Guyana — with sugar relegated to play only a minor role in our story.

Why Guyana Needs to De-emphasize Sugar and Diversify into Other Foods

De-emphasizing sugar means converting some 100,000 acres of abandoned cane lands to other crops. These lands already had intricate D and I infrastructure and access roads laid down, however in need of rehabilitation.

De-emphasizing sugar means Guyana automatically releasing itself from world market control and dependency, and concentrating on the Caribbean food market on which Guyana has a growing control and comparative advantage in production and pricing. Caribbean countries right now are seeking to reduce their extra-regional food bill and are looking towards Guyana for leadership and salvation.

Caribbean extra-regional food bill is “scandalous” according to former Secretary General of Caricom, Alister McIntyre who drew to the attention of Heads of Government of the 1976 alarming food import bill of US$1,000m. Half a century later, politicians are still talking. In 2000, the region’s food bill skyrocketed to US$2.08B, and to US$4.25B in 2011 with only 12.7% originating from within the region. In just over nine years, the region’s food import bill is now US$6B, 87% of which (over US$5B) comes from outside the region.

Imagine Haiti whose population is largely agrarian, with an annual population growth rate only about 1.2%, but its 2021 extra-regional food bill increased by 13% from the previous year. Most of the other Caribbean islands are in the same ocean, only slightly different boats.

Today, Caricom countries, which possess such great soil, and a population of only sixteen million people, have an exorbitant food import bill of $6 billion and more every year, a matter that has been of serious concern over the past years by several Regional and International Organizations that have all noted that these countries which experience very low or no economic growth, extremely high ratios of debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and declining foreign exchange earnings in many of the 14 independent nations that comprise the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the majority of them continue to spend huge sums on buying food outside the Caribbean.

“Pity the nation that eats a bread it did not harvest.”

Time for the Caribbean people to start leading their politicians. Of the nine featured speakers that addressed the forum held on Feb 10, 2023, under the theme ‘Investing In Vision 25 By 2025’ all were politicians. They quoted Alister McIntyre’s 1976 quote and they came up with a dream to reduce the US$6B bill by 25% in two years’ time, and in the next breath declared that they had already achieved 57% of that target. It was reported that products such as cocoa, dairy, meat, root crops, fruits, and poultry have already reached 96.13%, 84.36%, 72.28%, 70.91%, 70.77%, and 70.19% respectively for the targeted production volume set for the year 2025. They forgot about rice and flour, very dear at shop.

The largest Caribbean extra-regional imports are rice and wheat. (Haiti imports all its wheat and 80 percent of its staple diet –rice.) There is little doubt that Guyana can supply the entire Caribbean with rice. About wheat? Well, there are three countries with similar climate and topology as Guyana with their 2022 wheat production of 106 million tons, 9.5 million tons, and 3.3 million tons. They are India, Brazil, and Mexico, respectively. Also, about a dozen countries in Africa produced a total of 30.5 million tons in 2022, the leading producers being South Africa, Algeria, Morocco, Ethiopia, and Egypt. What does this say about possibility and potential of wheat production in Guyana?

They have further stated that Guyana, of all 15 Caricom states, has the largest land mass, the most arable agricultural lands, and the greatest potential for food production. It is shameful that golden opportunities to produce more food in the Caribbean and significantly reduce the astronomically high annual food import bill of US$6 billion are being woefully neglected. If this misguided trend continues, the economies of many of the countries of the region will be increasingly imperiled.

PRESENT SUGAR SITUATION

Sugar in Guyana faces a bleak future when viewed against international background as well as its own very sensitive local conditions of politics and race and heavy government subsidization.

At the international level, the global sugar industry is an “arms race”. As presently constructed, it shows a complicated maze of producing, exporting and importing countries operating through an enormous range of import restrictions (quotas and tariffs); production and export subsidies (preferential loans and credit); subsidized inputs, price support; and, even dumping schemes, gross market-distorting protectionism with four countries, having more or less dominating global exports of sugar and thus controlling world market price: Brazil, Thailand, India, and Mexico. All these countries heavily subsidize, or otherwise provide direct supports for sugar production and its export. Brazil spends about US$3 billion on preferential debt programs, input subsidies, usage mandates and bailouts.

As a result of this “arms race”, the International Sugar Organization (ISO) is presently forecasting a global surplus of nearly 4 million tons of sugar.

This is the international scenario in which featherweight Guyana whose 2021 production of 58,000 tons (with cost of production three times the cost of world market price), is thrown into battle against, say, heavyweights like Brazil whose 2021 production was over 65,000,000 tons. So, it’s time to be realistic. We cannot compete against such giants in the world market.

Because of its historical antagonistic mode of production, its inability to compete at the world stage, its current insolvent situation, and other current adversarial conditions – both international and local, the Guyana sugar industry, wholly owned by the Guyana State, and operated by the Guyana Sugar Corporation Inc. (Guysuco), is in a morbid crisis, facing one of two imminent fates – depending on which party is in government.

Either be permanently subsidized by one government to the tune of $5 to $10 billion annually which is a sore issue with opposition forces whose disagreements are more and more translated by their supporters to mean racial violence against people perceived as government supporters, or, be (vindictively) shut down, if, and when the other party gets in power (a highly realistic possibility, given their way of “obtaining” power the past fifty years), opting to keep only one or two estates operating just to satisfy local demand (of about 22,000 tons), and throwing some 15,000 workers in the street without any compensation as was done with four previous estate closures between 2016-2017. (Wales, Enmore, Rosehall and Skeldon).

Note: History does not have a starting point. A researcher chooses a starting point or timeframe depending on their established hypothesis and the data within that timeframe that will support such hypothesis. Guyana sugar economics, from the very historical inception, has been intricately connected with politics, and the politics of racism, to be more specific — an issue to be discussed later. Suffice it to note here that sugar was facing imminent economic collapse in the first quarter of the nineteenth century while slavery was the economic mode of production and the main source of labor in the production process (Eric Williams) and was only revived, not by any significant improvement in capitalization and management or in any other factor of production, but by “a new form of slavery” (Hugh Tinker.) Indian Indentureship, therefore, not only revived sugar, but kept it alive from 1838 to 2009, with enabling support from TWO main factors — efficient capitalization and management practice, (both pre {1976} and post {1989-1993} Nationalization) by Bookers/Tate/Jessels, with strong pre-nationalized reforms under Fabian Socialist Sir Jock Campbell; and more importantly, preferential European and US market treatment from 1959 to 2009.

These two life-supporting factors are now gone.

So, for now we may say that the crisis facing Guyana sugar industry became more desperate from the time it lost its European preferential market in 2009 and had to sell its raw sugar at world market prices at one-third its cost of production. Thereafter GUYSUCO began to display chronic problems, including migration of skilled and experienced managers, exhaustion of its cash reserves, deteriorating field infrastructure and factories and an unstable and adversarial industrial relations climate.

The decline initiated a domino, or reverse multiplier effect. Some results are:

Production

At the time of nationalization, 1976, sugar production had reached 350,000 tons. In 2021 it was 58,025 tons.

One must note that after nationalization in 1976, and prior to the 2009 loss of preferential markets, Guysuco has faced many challenges but was able to maintain average sugar output of 328,000 tons until 1992, and after 1992, close to its reduced target of 250,000 tons (reduced as a result of a severe drop in world market price), with an annual average of 264,983 tons of sugar in the decade from 1996 to 2005, and 208,718 tons in the subsequent decade of 2006 to 2015.

Guysuco’s decline had actually become noticeable not long after nationalization, but the blame was consistently laid on unfavorable weather conditions and workers’ industrial actions even though average annual production during the decade of the most industrial unrest and political oppression of sugar workers was 328,000 tons, the highest for any other decade in the history of sugar production in Guyana.

The 1993 World Bank report on Guyana Sugar states: “The decline in output to 130,000 tons was due to a combination of an unfavorable macroeconomic policy environment and inappropriate Government policies which drained resources from the company and limited its access to scarce foreign exchange resources. Financial problems were compounded by ensuing serious difficulties on the production side. Agricultural, field infrastructure and processing plant and equipment deteriorated, the supply of spare parts and agricultural inputs was inadequate.”

When they could no longer transfer blame to weather and workers for declining of the industry, the Government sought Booker Tate assistance in December 1989. As part of the agreement, the Government signed, on October 1, 1990, a management contract with Booker Tate, extended until December 1993, to: (a) take over all day-to-day operations of Guysuco; (b) prepare a feasibility study to rehabilitate and rationalize the industry; and (c) take steps to identify private and official financing sources for the investment program under the feasibility study. With the arrival of a qualified management team, agricultural and processing practices improved. Wages were increased. This reduced labor unrest and resulted in the return of the labor force. An IDB loan for spare parts also eased the financial and foreign exchange constraint enabling a small number of investments. These actions, together with two years of good weather, allowed Booker Tate to bring production to around 160,000 tons in 1991 from 130,000 tons in 1990, an increase of about 25%. This level of output allowed Guysuco to meet the EEC quota for the first time in four years. Production reached 243,000 tons in 1992, near the expected optimal market for Guyana sugar of about 250,000 tons and allowed Guysuco to meet all its yearly quota obligations to the EEC and USA markets, catch-up with the unfulfilled EEC and USA quotas, and supply all domestic sugar requirements.

That Booker Tate was able to arrest the rapid decline of Guysuco points to a management incompetence that has been plaguing the industry ever since nationalization in 1976. Booker Tate involvement since nationalization is summarized as follows:

• 1976 Sugar industry nationalized, and Booker Tate provides limited assistance.

• 1990 Booker Tate signs full operational management agreement.

• 1996 Sugar production reaches 280,000 tons.

• 2002 Sugar production reaches 331,067 tons – highest since 1976.

• 2005 Contract signed to build the new Skeldon factory and cogeneration plant.

• 2008 Booker Tate continued to provide services under the operational management agreement and project management services for the new Skeldon factory.

• 2009 With completion of the Skeldon factory, Booker Tate’s contract was completed.

What Bookers Tate had basically done was to re-apply the Jock Campbell Fabian management philosophy.

Lord Jock Campbell who had spent more time living in and amongst working people in British Guiana and studying the sugar industry than any other management personnel, advanced the thesis, in 1949 that the success of sugar had to be grounded in three fundamental principles: (i) the efficiency of the industry; (ii) the price of its products; (iii) the “human relationship” within the industry and the planters.

Under his control before Nationalization in 1976, Jock Campbell followed his committed philosophy that: “People are more important than ships, shops, and sugar estates.” With such a vision at the highest level in the sugar industry, workers acted in the belief that they were a critical element to the business and conducted themselves accordingly with an enhance level of efficiency and as agents against wastage in the industry.

Sir (later Lord) Jock Campbell’s socialist statement that “people are more important than ships, shops and sugar estates” basically summarized one of the two institutionalized alienations that have been taken for granted throughout the existence of sugar — the alienation of labor from the mean, mode, and relations of production; and the alienation of the industry from external market mechanism.

Alienation of Labor

In the first place, the sugar industry has historically employed a mode of production totally different from any other agricultural industry. First, it was slavery when labor was a property, like capital, owned by the industry, to be used and abused at the whims of the industry. Later, from indentureship to present, labor became a commodity to be purchased at a price determined solely by the industry through a fundamentally asymmetric power relationship between the poor workers and the powerful owners. This asymmetric relationship between labor and owners gave rise to strong labor unions and nationalist political parties trying to bargain for a livable price for labor. Conflicts ensued – sometimes violent, sometimes deadly. The history books are rife with countless incidents of bitter confrontations, uprisings, riots, strikes, sabotage, teargassing, widespread arson, seizure of strike reliefs, etc. This antagonistic relationship between the laboring class and the ownership class became even more confrontational after nationalization when the laboring class began to perceive themselves to be racially and politically marginalized. Strikes, arson, sabotage, stealing and mediocre labor and managerial performance increased. In addition to a decreasing labor supply with its concomitant higher labor price, these all contributed to a rising cost of production and at the same time decreasing productivity at all levels of the production process, a trend which continues to this day. Labor in Guyana, whether, slave, indentureship, or wage, has always been alienated from the means and relations of production. They had no ownership nor say in the entire production process.

One of Jock Campbell’s most successful implementations in addressing labor alienation from the means of production was the Bellevue peasant cane farming scheme implemented in 1956 whereby fifty-seven first class canecutters were selected from all the estates for a pilot project and given a house and fifteen acres of cane lands as their own to cultivate. For over fifteen years those lands produced the most efficient tc/a and ts/tc ratios in the country (tons cane per acre and tons sugar per tons cane). Unfortunately, these field productivity ratios began to fall when the original set of canefarmers became absentee owners or began to employ wage labor to work their fields.

Alienation of the Industry from International Pricing Mechanism

The sugar industry is alienated from a market system that dictates not only price and quotas for its product, but specifically limits the industry to the production and export of raw or semi-processed sugar. In addition, not only the price for exported sugar is exogenously controlled, but also the buyers control the price of much needed inputs — machinery and agro-chemicals, that Guysuco must purchase from them to produce sugar. It’s a lose-lose situation with the terms of trade completely in control by the EEC/US markets. These dictated prices for both exports and imports seldom or never changed in favor of the industry. Thus, the industry had always been at the mercy of a regressively worsening terms of trade which, added to the rising cost of labor, added to the per unit production cost of sugar. The terms of trade have been deteriorating for decades, and there are no signs that the situation will improve or reverse for years to come. Besides, for Guysuco to stay in the highly competitive world market, while remaining a state-owned entity there is grave danger of the state directing scarce resources to subsidize sugar. Unfortunately, sugar subsidization, an acceptable practice of every sugar producing country in the world, including the US, is a very controversial political and racial issue in Guyana which, sadly, has played a major role in swinging recent general elections.

It is primarily because of these two alienation factors that the sugar industry and the country as a whole are caught up in a Sargasso-like dependency syndrome and hence a perpetual state of underdevelopment. It must sell unprocessed bulk goods to the developed countries; it must not and cannot industrialize – any industrialization done must be to increase production and productivity, and to a very limited extent only, processing (like what Guysuco and the government are so myopically currently doing); it must buy their manufactured goods – and all these at prices dictated by the developed countries.

This is the nature of the cycle of sugar economics dependency. A gradual break away from this system was not previously possible because the necessary capital to power such breakaway could only be obtained from western capital markets at terms that perpetuated dependence. You see, the neo-liberal market system has deeper origins and a multitude of cancerous tentacles, a break away from which requires holistic re-education, indoctrination, social and political re-alignments – a transformation which may be particularly difficult for westernized populations and leaders lacking vision, courage, or ideology to accept.

Income and Profitability

During the 1990s the corporation earned a profit, averaging G$3.9 billion, but this went into reverse, and the amount of losses nearly doubled in the 2000s, despite Bharrat Jagdeo’s discontinuation of the levy in 2003. (In its 29 years of existence, the levy had siphoned out US$1.65B before profit from the industry.) Not surprisingly, the profit situation dramatically worsened over the years.

At the time of the 2016 – 2017 closing of the Wales, East Demerara, Rose Hall and Skeldon sugar estates, Guysuco was the largest employer in the country with a staff of 16,000 and around 160,000 people (one fifth of the population) indirectly dependent on its operations. However, sugar, largely produced for an export market, often struggled to garner sufficient demand, and maintain competitiveness in global markets. The drastic decline in exports (foreign exchange earned) from US$123 million in 2011 to US$49 million in 2017 and US$27.7 million in 2019 reflect the challenges faced by the state-owned sugar industry, managed by Guysuco.

Employment costs accounted for 48 percent of total costs from 2010 to 2015, thereby absorbing 73 percent of the revenue earned by Guysuco during that period. The dire revenue situation coincided with the loss of preferential markets and prices that the company enjoyed from 1976 to 2009.

A subsequent debt of more than G$82 billion (US$410M) between 2010 and 2020 was incurred by Guysuco.

From a static, ahistorical, purely statistical point of view it would seem that a production drop from 234,000 tons of sugar in 2009, to107,203 tons in 2019, further declining in 2020 to 87,875 tons, and plummeting to 58,025 tons in 2021 may be attributed to the EEC market loss of preferential treatment. But the reader will see that this market loss was not the cause, but one of the inevitable results a problem more chronic, deeply historic and institutionalized which can only be corrected by transformational means.

As an aside, it must be noted that Guysuco was notified and informed by EEC at least 20 years before that its preferential market treatment was going to be phased out gradually. During the PPP management years, the EEC had also generously provided aid to Guysuco to enable it to diversify production and improve its field and factory productivity. In 2014, the local European Union (EU) representative confirmed that Guyana received €136 million (G$32 Billion) from 2007 to 2013 under the Accompanying Measures for Sugar Protocol Program (ASMP). The financing was the penultimate one in what was a deal started in 2006 to buttress the sugar industry from the expected fallout from the removal of the Sugar Protocol.

EU grants were made to Guyana and 18 other African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries, following the decision to discontinue EU preferential sugar prices to these countries.

The €136 million (G$32 Billion) has not been accounted for by the government (current opposition party). Further examination by researcher showed exorbitant wasteful expenditure on expensive, inappropriate agriculture machinery, tilling methods, cloudy technical assistance and consultations, and failed diversification expeditions.

In addition to the €136 million given between 2007 – 2013, another €34 million was allocated to Guyana in 2014 under the 11th European Development Fund for sugar and other Budget support modalities.

But in 2015, Britain’s High Commissioner, Andrew Ayre is on record as saying that his country (which is an EU member) would not favor the disbursement of British taxpayers’ money to Guyana in the absence of parliamentary oversight and proper accountability. Later that year the European Union (EU) announced the temporary suspension of undisclosed millions of Euros to Guyana for the sugar sector, citing the need for a transparent and accountable system for the spending of European taxpayers’ monies.

Also, asked whether they were satisfied with how 2007 – 2013 money had been spent EU Delegation Head Robert Kopecky said they wish to see more of the money going towards the sugar industry. He noted that in the beginning they were operating under different circumstances with the funds meant to mitigate the effects of the removal of the preferential markets. “I understand that some money has been invested in related things like education, social cohesion et cetera. But still with the not growing sugar industry… we’ve been consulting each other saying this is probably not the way to continue for guaranteeing the sustainability of the industry in the future. It must be more targeted to the industry itself,” Ambassador Kopecky said. He highlighted conversion of land, mechanization, private farmers’ support and investment in pumps and drainage as areas in which they would like to see the money spent. Basically, the EU wanted budget support funds spent on sugar industry, not in other areas where not directly related to sugar.

The then Opposition, APNU at a news conference said that it was “a mystery” why the EU funds were not being dedicated to the sugar industry despite a pronouncement from the then President Donald Ramotar that the industry was near a crisis state.

Wastage, squandering, and corruption were equally rampant during both regimes.

But Professor Clive Thomas’s 2015 COI recommendations of privatization, juggling finances, restructuring debts, splitting up of Guysuco into a dozen independent, self-sustaining entities –basically the kind of shuffling an accountant would do for short run satisfaction were not surprising, as they were based on testimonies of some two dozen or more current or former top incompetent brass of Guysuco , none of whom had probably ever heard the term, ‘development economics’, and if they had, had no interest in it, because, sadly, that is the difference between a businessman and an economist. One is concerned about profitability of the entity, the other in the welfare of the people in the entity.

Although Thomas specifically advised no sugar estate closures in his recommendation, the government went ahead and announced the closure of Wales, blatantly stating that the closure was, “in line with Thomas’s recommendations.” Then, later the President stated, “Govt. had no obligation to fully conform with Guysuco’s recommendations. The (Thomas) COI is not gospel.” He said, “We have practical measures to consider and in the case of Wales it is very practical to close the estate.” Most of Thomas’s recommendations were ignored — atypical of both APNU and PPP to ignore expert advice. The only part of Thomas’s recommendations that was honored was privatization of cane lands which the President took full advantage of and stated, “Maybe it is an opportunity for a wider application of the principle of peasant cane farming. So, it is not as if the sugar industry is in jeopardy, but I believe that peasant cane farmers can take up the land and that has been tried already in some parts of West Demerara.” But then, the President went back on his own words. Absolutely no land was given out at Wales or any other of the closed estates for peasant cane farming. As a matter of fact, weeks before demitting office which they held as Caretaker government only, 65% or 5,397 acres of Wales 8,352 acreage was leased to 164 private entities just prior to 2020 general elections. The officer in charge of Wales Estate, himself, took 27.2 acres, a Dr. Cambridge was given 144 acres, a Rayo Inc. 752 acres, an unknown entity at Potosi 806 acres and another unknown 334.7. The largest recipient was a Nugget Gold Inc. of 1,079 acres. (Incidentally, research could not establish authenticity of such a company.) Three years after, almost all these lands remain undeveloped. These land giveaways were indirectly part of Professor Thomas’s recommendations of privatization.

Soon after these estate closures, the government secured a $30 Billion syndicated bond to ‘revitalize’ the remaining three estates over a four-year period. Four years later, it was disclosed that the money was exhausted, but neither the government nor Guysuco can to this day give a full account of how, when, where, and why the amount was expended. This obviously raises a red flag with a clarion call for a forensic accounting investigation.

Guysuco had been a cash cow from the time of Burnham’s 1974 tax levy, a levy which deprived workers of wage increases and profit sharing of $US1.65B, or an annual average of US$57 million for some 29 years (close to $US 3.5B in today’s money) from the time of imposition of the levy to the time it was abolished by Bharrat Jagdeo in 2003. But by 2009 as its death bells began to toll and government subsidies started to flow, every politician from both sides of the aisle, as well as Guysuco echelon and their relations were milking it. No wonder Professor Clive Thomas had to say, “I am never satisfied once injustice exists. I feel very outraged that the previous administration stole so much from the public. I honestly will feel better after I have successfully completed this State Asset Recovery Program and those who stole from our beautiful nation are made to face the time.”

The real fear, however, is that this corruption, inefficiency, and wasteful spending on unsuitable methods, machinery and management will continue, to drain the agency, while at the same time surreptitious white-collar looting is taking advantage of the industry’s distress, which is not dissimilar to the looting of businesses when people riot or when businesses are in danger of going under.

In seeking a way forward for Guysuco, I would like for us to philosophically examine how we came to be in this position of insolvency. For, herein lies, not just the cause of the demise of sugar, but also the answer for returning it to viability. Indeed, too many people have interpreted and analyzed the demise of cane sugar from an economic or accounting perspective; few have done so from a philosophical/sociological one. It is not surprising therefore, that none of the corrective measures, suggested or applied so far, seems to be working.

In my philosophic examination, I would like to start with the premise that the history of sugar has never been associated with the development of Guyana, development being defined as a sustained increase in the economic standard of living of the country’s population, normally accomplished by increasing and improving the quality of its physical and human capital, and by improving and increasing its technology and the general industrialization of the country.

Thomas’ Neo-Marxist Solution

In the Commissioner of Investigation report of 2015, Professor Clive Thomas was very detailed and accurate in analyzing the problems facing sugar in Guyana, but he failed to come up with any transformational solution, understandably because he was committed to base his conclusions and recommendations on the testimonies of some two dozen Guysuco top brass, none of whom were development economists, or probable had the interest of the country at heart. Nevertheless, it was uncharacteristic of Clive Thomas who had studied and written profusely on the subject. His “Plantations, Peasants and State: A study of the Mode of Sugar Production in Guyana” is a neo-Marxist dependency analysis of the long history of the sugar industry in which he maintains, “sugar production has been the major economic activity underlying the colonial penetration, later capitalist consolidation, and subsequent underdevelopment of the national economy of Guyana”. Thomas’s book entered the pantheon of economic polemics that postulated that in the world economy, the Periphery (the Third World) will always be exploited by the Core (the advanced capitalist, West) unless it breaks away from the world economy or change the world economy completely. His Dependence and Transformation advocated structural and ideological changes in the very mode of production – and subsequently the forces of production and the relations of production, so that small economies can escape from the doldrums of imperialist dependency. This syndrome of dependency is sustained by two pillars – a dependency on western market economy; and a maintaining of a mode of production that closely approximates the slavery mode which is characterized mainly by its antagonistic relations between labor on the one hand, and other forces and factors of production on the other. In other words, labor is alienated from capital, management, and most of all, from the very land that they till (even though the Constitution stipulates that land should belong to the tiller.)

To break out from this syndrome we need to address structural issues in the western market system on which all our economic activities and our social and political infrastructures are built. The western market system is not compatible with eastern and African cultures. People caught in its orbit easily become part of it, as it also becomes part of their individual and social psychology. Limitless accumulation, unfathomable greed and corruption, drugs, crime and violence, and especially copy-cat western lifestyles are all derivatives of the western market system. The western market system is nothing more than a socially evolved phenomenon with a structural characteristic, which, only after recurrent, devastating world wars and depressions and persistent poverty of the masses, came under some government regulations associated with John Maynard Keynes. But it is ruthless and, unlike most human organisms and humane organizations, lacks philosophic morals and mottos to direct their goals and objective in life. The western market system does not strive on profit, but on the increasing rate of profit, or as we say in differential calculus, the first and second functional derivatives of profit. In other words, it is not that profit, or exploitation must increase, but the rate of that increase itself must increase. Western market system inherently contains the cancer for destruction, and dialectically including its own destruction.

That is why even traditional economic analyses generally based on Keynesian and Friedmanian market economic paradigms cannot adequately explain or cure chronic Third World post-colonial poverty. Indeed, they barely explain the mechanics of capital market, poverty, depressions, and wars resulting from accumulation and greed, but cannot explain the cure. In the aftermath of World War II and Cold War I, several political economists expounding the theory of Transformation burst out, the greatest among them, Karl Polanyi who propounded the theory that over-globalization, while there were some good aspects such as new technologies in communication and transportation, expanded trade and capital flows, tied up the world too closely and made countries more susceptible to wars, economic depressions, dependency, and multinational market controls. Polanyi was the father of Transformation economics, and his work must have inspired Clive Thomas, since their works shared many similarities. But more importantly, why I mention Karl Polanyi is because most economists are humane people with a deep sense of moral responsibility, who have been indiscriminately, academically, and sincerely pursuing the DEVELOPMENT of fellow human being, and Karl Polanyi, father of Transformational economics, was there, head and shoulder taller. He died the year Clive Thomas earned his PhD. Before he passed away, he wrote to a friend, “My life was a ‘world’ life—I lived the life of the human.” We may judge Karl Polanyi by Matthew Arnold’s words — “Truth sits upon the lips of dying men.” This is the creed by which true development economists should live.

WHAT IS DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS

Development economics is about restructuring and transformation of the means, forces, and relations of production as well as markets and supportive educational and vocational institutions; hence it incorporates social and political factors to devise particular plans that not only promotes economic development, economic growth and structural change but also improves the potential for the mass of the population, through health and education, work ethics, family and community values, racial harmony and social cohesion. directly focus on the elimination of poverty, hunger, greed, crime, and making good health, education, recreational and cultural services and amenities within the reach of all; and all of these while preserving the environment and the delicate balance of nature. What is the sense in boasting a 50% growth rate and having fifty percent of your population living below poverty line? Or people dying needlessly because simple healthcare is beyond their reach? Development is not measured by fantastic growth rates of GDP. Indeed, we need to observe the Bhutan concept of measuring development by Gross National Happiness (GNH), an index which measures the well-being of the population, rather than the wealth of the nation. In doing so, we need to deviate – even a little bit gradually from the corrupt and dominating western market system which directly influences our morals, values, religious behavior, societal status and relations to the factors and forces of production.

Aside from Thomas, there were other dedicated Caribbean economists who developed workable transformational models. One of them, Sir Arthur Lewis, spent practically his whole life articulating models for developing countries, in particular those that are predominantly agrarian with a surplus rural labor, and enjoying a comparative advantage in agriculture production. For him, agriculture, along with agro-based industries, was seen as the engine of growth that would transform over time the economic, industrial, and institutional structure of an underdeveloped economy. For this he was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. Unfortunately, his expertise was not adequately utilized in the Caribbean. Today, the Caribbean, aplace that has such great soil, and a population of about six million people, has an extra-regional food import bill of $5 billion and more every year. What lesson is there for Guyana, the breadbasket of the Caribbean, to learn? We need to take advantage of the Caribbean US$5billion food import. We are now in the driving seat. We have all the agricultural potentials, climate conditions, comparative advantage, and most importantly we do not now have to go to western markets for financing under their terms that perpetuate western market dependency.

As stated before, past efforts to improve the performance of Guysuco have been ineffective because they failed to address the issues of alienation of labor and alienation from the pricing mechanism. But they also failed because they were short-term planning, and piece-meal improvements; they addressed the symptoms of the problem, not the problem itself, and involved little or no structural change of the industry nor the economy. For industrialization and development to take off, holistic long-term planning and structural changes are required. Development Economics theorists agree that a country must start on an industrialization path with that economic activity in which it enjoys a comparative advantage. For Guyana it unarguably agriculture, but not with sugar continuing in the driving seat.

While sugar may still have a comparative advantage as a foreign exchange earner, and through the multiplier and linkage effects, provides a living for five times as many families as actually directly employed, it must be admitted that these effects are diminishing and dissipating. But most importantly they are stifling the growth and development of other Agri products and their secondary/tertiary processing, even by mere usurping or diverting of the labor force and capital. It is also, in concentrating on supplying already saturated EEC, US and world markets with sugar, inhibiting regional trade in much needed breadbasket items which Caricom partners have to buy from extra-regional sources.

A Challenge to Guysuco

To remedy this situation and effectively break out of this syndrome, it is imperative that the government and Guysuco undertake some immediate structural changes, or the industry will die a natural death which would result in serious racial, political, economic and social insecurities. Foreign exchange would be reduced, national income would shrink in response to an inverse multiplier effect, and the economy would experience a lop-sided growth rate resembling that of Venezuela and other countries stricken with Dutch disease. Unemployment and inflation would soar, and the unemployed would resort to survival by any means necessary such as crime, marijuana cultivation and cocaine peddling. One should note that these three activities are already prevalent in Wales, a direct result of closure of the estate and termination of their means of living. I know about Wales because I am from that area.

As stated before, past efforts to improve the performance of Guysuco have been ineffective because they failed to address the issues of alienation of labor and alienation from the pricing mechanism. But they also failed because they were short-term planning, and piece-meal improvements; they addressed the symptoms of the problem, not the problem itself, and involved little or no structural change of the industry nor the economy. For industrialization and development to take off, holistic long-term planning and structural changes are required. Development Economics theorists agree that a country must start on an industrialization path with that economic activity in which it enjoys a comparative advantage. For Guyana it unarguably agriculture.

Transformation

In essence, we are talking transformation of the economy.Transformation is a painful process for westernized populations, and leaders lacking vision, courage, or ideology are reluctant to take that route. But transformation does not necessarily mean going socialist, and they can even adopt Sir Arthur Lewis’ western model for developing countries that are predominantly agrarian with a surplus rural labor and enjoying a comparative advantage in agriculture production. But these agro economies must proceed from primary to value-added, secondary, and tertiary processing in order to capture the market and become the engine of growth that would transform over time the economic, industrial and institutional structure of their underdeveloped economies.

Diversification is the Means by which this Transformation canbe Effected

Should Guyana accept this challenge and adopt this proposed path and model to development, then the Diversification of Guysuco should be the main instrument through which this can be accomplished. Guysuco must play the most significant role in the transformation of Guyana. One should note that in the colonial 1960’s when sugar was king and contributed directly and indirectly as much as 60% to the GDP, British Guiana was sometimes called Bookers Guiana. Today, Guysuco is just a small entity owned by the government, and its contribution to GDP less than 10 percent. But for Guysuco to be the engine of growth and play a prominent role in Guyana’s development it must move away from sugar.

Moving away from sugar towards diversification is the only way Guyana can break out from this dependency syndrome. It must produce goods for which there are ready and growing markets, goods that are in demand, and for which the pricing mechanism is not totally out of Guyana’s control. It must produce raw as well as canned fruits and vegetables, grains and legumes, meats and freshwater fish, dairy, dairy products, and confectionary,which are in heavy demand by Caricom countries and the diaspora in North America. It must take advantage of Caricom’s $6B food imports from extra-regional sources. to satisfy its population of sixteen million, as well as the six million visitors to the region every year, vacationers who come to the Caribbean and are given pineapples from Hawaii, guavas from Mexico, oranges from California, and sapodillas from India. The North American markets might be even more attractive, while neighboring Venezuela might also be a potential market.